Presidential Transition Guide

Transition Overview

Candidates running for a first term must not only devote their time and energy to winning the election, but must simultaneously set up a transition organization to lay the groundwork for governing. Presidents seeking a second term also need to engage in planning for the next four years as discussed later in the guide.

An effective presidential transition requires naming transition leaders, establishing a clear set of priorities and a robust work plan covering policy, personnel, federal agency review and a host of other issues. The transition leadership must develop a cooperative relationship with the campaign, have sufficient resources and, if the candidate is victorious, be ready to undertake a two-and-a-half-month sprint to the White House. This chapter offers an overview of the transition process, followed by a more in-depth look at the various aspects and phases of planning for the transfer of presidential power.

Fundamentals of Getting Organized

Preparing to take over the functions of government is immensely complicated and requires extensive preparation. Managed well, it can result in a new administration ready to take immediate control of the presidency. Managed poorly, it can lead to delays in staffing key positions, strategic errors in policy rollout and communication and, at worst, difficulty responding to pressing national security and domestic challenges.

Given the sheer size and complexity of the federal government, transition planning is a daunting task. An incoming president is responsible for making more than 4,000 political appointments, managing an organization with a budget of over $6 trillion and overseeing a workforce of more than 2 million civilian employees who perform missions as diverse as national defense, public health and citizen services. Any candidate for the presidency must be ready to handle the demands of leading a massive organization that operates much like a holding company for disconnected entities and not enough like a unified whole.

One inescapable feature of presidential transitions is the calendar—there will be an election and there will be a finite amount of time in which to prepare for the move from campaigning to governing. Therefore, a whole-of-government approach should begin no later than spring of an election year—and preferably sooner.

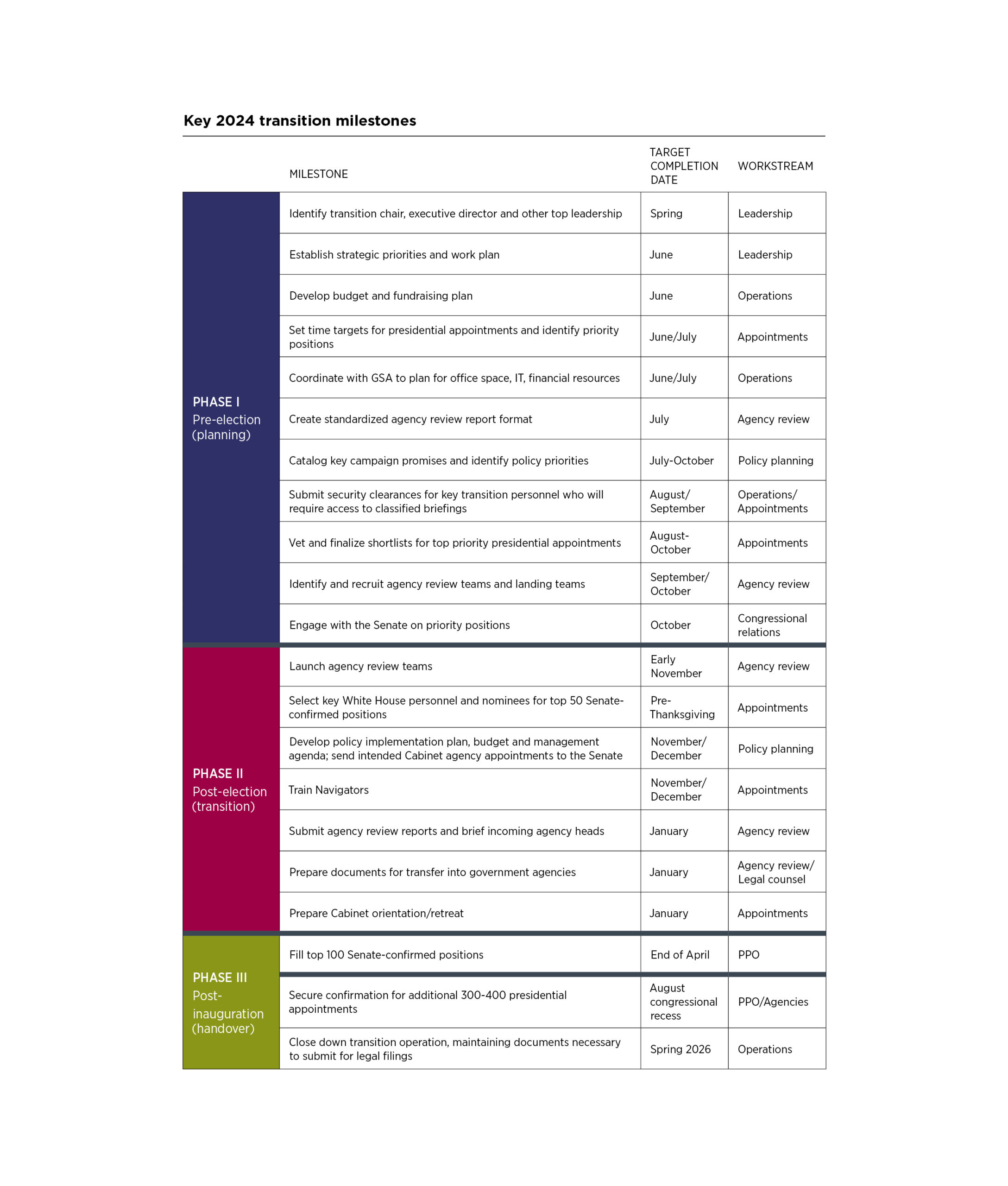

Transition timeline

The full presidential transition process consists of three main phases, covering roughly one year, from April or May of the election year through the inauguration and the new administration’s first 200 days. The tasks, pace of decisions and number of transition personnel increase exponentially with each phase.

In the pre-election phase, transition team leaders must set up the core operational units of the transition, bring transition staff members onboard and engage in extensive policy and personnel planning.

In the post-election phase, campaign staff are merged into the transition, and the volume of work sharply escalates to scale up personnel vetting, policy planning and agency reviews. The number of transition personnel can jump from a few dozen prior to the election to more than 1,000 staff and volunteers by the eve of the inauguration. With roughly 75 days between the election and inauguration, incoming administrations have a very short time in which to learn and accomplish all that is necessary to assume the responsibilities of governing. A full description of staffing and organizing the transition team can be found in Chapter 2.

During the post-inauguration “handover” phase, responsibilities become vested in White House and agency offices, and the transition operation is officially closed down.

The major activities in these three phases are:

Pre-election “Planning” Phase

Planning for a presidential transition should start in earnest in spring of the election year. Key activities in this pre-election phase include:

- Naming a transition chair.

- Assembling and organizing the key transition team staff.

- Setting goals and deliverables for the transition.

- Assigning responsibilities among the team members.

- Allocating resources for each workstream.

- Developing an overall project plan to guide the team through the entire transition process.

- Establishing relationships with Congress, the current administration, the General Services Administration, the Office of Government Ethics, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Office of Personnel Management.

In April 2020, Joe Biden named Ted Kaufman and Jeff Zients as transition co-chairs. In 2016, Donald Trump named his transition chair during the first week of May, and the pre-election transition effort was launched in June with about eight staffers. Hillary Clinton’s campaign planned her transition strategy during the early summer months, but did not officially announce transition leaders until after the Democratic National Convention. In 2012, Mitt Romney’s team began planning in June of 2012, although some initial planning took place in April and May. In 2008, Barack Obama’s transition team began its preliminary work in April and formal planning in May.

Early planning has been facilitated by the Pre-Election Presidential Transition Act of 2010 (Public Law 111-283), which made office space and equipment, information technology and staff assistance available to eligible candidates through the GSA following the nominating conventions. The Romney transition operation was the first to have access to transition support before the election and was able to move into government-supplied office space by early September 2012. In 2016, the Trump and Clinton campaigns both moved into the GSA office space in Washington, D.C. on Aug. 1 following the conclusion of the Republican and Democratic political conventions with most in-person work reserved for post-election sensitive agency and national security briefings.

Post-election “Transition” Phase

In the roughly 75 days between election and inauguration, the transition team must increase hiring, often through an influx of campaign staff; integrate them into daily operations; and prepare to take over the functions of government. Key activities in this phase include:

- Staffing the White House and agencies.

- Deploying agency review teams to visit agencies.

- Building out the president-elect’s policy and management agendas

and schedule. - Identifying the key talent necessary to execute the new president’s priorities.

Post-inauguration “Handover” Phase

Following the inauguration and transfer of power to the next president, a new administration has a narrow window of approximately 200 days in which to achieve quick wins and build the momentum necessary to propel significant policy initiatives forward. The focus in this phase tends to be on identifying and vetting the right staff and appointees based on the president’s top priorities—a formidable task given that the new administration will fill roughly 4,000 political appointments, including more than 1,200 that require Senate confirmation.

The administration also will have to officially close down the transition operation and preserve important records for historical value and to aid future transition teams.

Closing down the transition operation once the new administration comes into office (or, for the unsuccessful candidate, when the election concludes) is typically overlooked during the frenzy of pre-election activity. Building the transition organization is intense and challenging, and it is easy to lose sight of the fact that at some point much of the work of the transition will need to be either transferred to the White House or otherwise archived.

The Presidential Transition Enhancement Act of 2019 allows the GSA to continue providing support services to the president-elect for up to 60 days after the election. The intent of the provision is to allow the transition team to continue time-sensitive work, around personnel in particular, in the transition space, without the forced disruption of moving the operation to the White House on Jan. 20. The Trump transition team remained in the federal office space until mid-February 2017 after revising its memorandum of understanding. The GSA agreed to provide the office space and guard service, and required payment for the accommodations, but did not provide any other support services after the inauguration.

Finally, transition operations should consider the importance of their work for future candidates and transition teams as well as the historical record. Given how critical the transition process is and the bipartisan nature of the need to prepare, transition documents and experiences will be of enormous value to future transition leaders. The Romney transition set a laudable precedent with its book, Romney Readiness Project 2012: Retrospective & Lessons Learned, which laid out the process by which that transition team prepared for a potential Romney administration. Such resources will be invaluable to future transitions as they undertake the crucial work of building a presidential administration from scratch. The closing of the transition operation provides an opportunity for this kind of archiving and reflection.

The Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition® serves as an online home for transition archives, including documents from previous transitions dating back to 2000, at presidentialtransition.org. More than 1,000 tools, templates and historical documents are available, including agency overviews, appointee position descriptions, templates for transition materials and other resources.