Presidential Transition Guide

Second-Term Planning

How previous administrations have approached second-term transition planning

Presidents seeking a second term are consumed by the day-to-day exigencies of the office and campaigning, and rarely use the months leading up to and following their re-election to absorb lessons from the first four years and plan for changes and adjustments.

For the most part, incumbents have not considered that a transition is occurring when they are re-elected because they already run the government and have people and policies in place.

In interviews, several former top White House officials said that neither George W. Bush nor Barack Obama engaged in significant organized transition planning during their successful bids for a second term. In hindsight, the former officials said, it would have been useful if they had a team of trusted aides lay the groundwork for implementing the major policy promises made during the presidential campaign, as well as identifying and planning for other critical second-term priorities.

“My instinct is that every two-term presidency has had the same problem, which is the president doesn’t think of it as a transition,” said Josh Bolten, Bush’s former chief of staff. “It’s a huge lost opportunity.” “We need to treat the re-election of a president as though it were a transition for both personnel and policy,” Bolten said. “It is a good time to bring in new people and to step back and refresh the whole agenda.”

Senior Obama officials described a similar experience. Denis McDonough, Obama’s chief of staff during his second term and a foreign policy advisor during his first, acknowledged, “I did not think about it as a moment of transition and I don’t think we as a team did.”

In the lead-up to the 2020 election and transition, White House Deputy Chief of Staff Chris Liddell incorporated second term planning into the work of his office. In late December 2019, Liddell organized a retreat for senior White House and Cabinet officials on policy and organizational priorities going into a second term – one of the few instances of second term transition planning being initiated in advance.

Former White House officials also said advanced planning on policy initiatives and personnel can position a second-term administration to capitalize on a window of opportunity following a president’s re-election. This timeframe also provides the administration with a chance to consider how to address controversial or intractable issues that were put on hold during the first term.

Second-term planning starts at the White House

A second-term transition should have at least two major components, one centered at the White House and the other involving assistance from agency leaders. The focus should be on two major strands of planning in year four: policy and personnel.

According to former presidential aides, the White House should oversee second-term transition planning. A separate transition entity makes sense for a candidate who is running for a first term, but not for an incumbent. The former aides said it would not be wise to create a stand-alone transition team outside of the White House that might be perceived as a competing power center or attract unwanted public attention. Instead, those overseeing the transition should have sufficient time to devote to the endeavor, have the president’s trust and be under the direction of the White House chief of staff or a designee. The focus, they said, should be on priorities going forward, informed by what has worked during the first term, what needs to be fixed or dropped, opportunities for new initiatives, the best strategies to achieve desired results, and the management changes necessary to improve government operations.

Policy planning

Although the policy direction of an administration is ordinarily crafted each year in preparation for the president’s State of the Union address in late January or early February, the transition offers a chance to start the planning process at a much earlier stage. The policy component will certainly mirror the campaign promises, but should also take advantage of the assistance of experts inside the White House and agency leaders.

The team planning for a second-term transition must position the president to move quickly on ambitious legislative proposals after the election, before the president’s relative power declines with lame duck status and the president’s position with Congress erodes. White House legislative proposals in the second term generally require more concessions and have a lower chance of passing. And a president’s window of opportunity to pass legislation closes quickly during the second term because the president’s party typically loses seats in the midterm election. In fact, since 1906, no second-term president has had his party gain seats in either the House or the Senate with one exception: the Democrats gained five House seats in 1998 when Bill Clinton was in office.

The second term also offers an opportunity to pursue initiatives that may have been too politically risky in the first term. George W. Bush, for example, chose to wait until after he was re-elected to try to reform Social Security. Bush’s 2004 campaign policy director, Tim Adams, explained that the administration wanted to be in a stronger political position before it took on the issue. “The president is adamant that we do it in a bipartisan way,” he declared. “And it’s such a big issue that it almost requires an election to give the president the political capital and the ability to frame the issue so that he can get his conceptual solution through a divided Congress.” Despite the timing, Bush was unable to win support for the always thorny issue.

Second-term presidents are more likely to find success in the foreign policy arena, where they enjoy greater freedom of action. Many presidents have pursued ambitious initiatives overseas during their second terms. Ronald Reagan negotiated a nuclear arms control treaty with the Soviet Union, Bill Clinton brokered the Good Friday peace agreement in Northern Ireland and George W. Bush launched the troop surge in Iraq. Barack Obama secured some of the most notable foreign policy achievements of his presidency during his second term, including negotiating the Iran nuclear deal, supporting discussions that led to the Paris Agreement on climate change, and restoring U.S. relations with Cuba. Second-term transition planning should account for the potential divergence of opportunities in the domestic and foreign policy arenas.

Personnel planning

On the personnel front, former White House aides recommended that the president and the chief of staff confer prior to the election about making changes in the Cabinet and among senior White House staff. In some cases, Cabinet secretaries may have already signaled a desire to leave at the end of the first term to pursue other opportunities. In other cases, the president may wish to request the resignations of some Cabinet secretaries based on performance, personalities and second-term priorities, and discuss replacements based on the policy, management and political skills needed to advance the agenda for the next four years.

When it comes to second-term transitions, there is no officially recognized rule that all political appointees must tender letters of resignation at the end of a first term and prior to the beginning of a second one. However, there have been administrations that have adopted the norm that appointees should not expect to be reappointed by the president for the second term and thus should tender a resignation at the end of the first one. This gives the president an opportunity to nominate new individuals without having the difficult conversation of asking an appointee to resign.

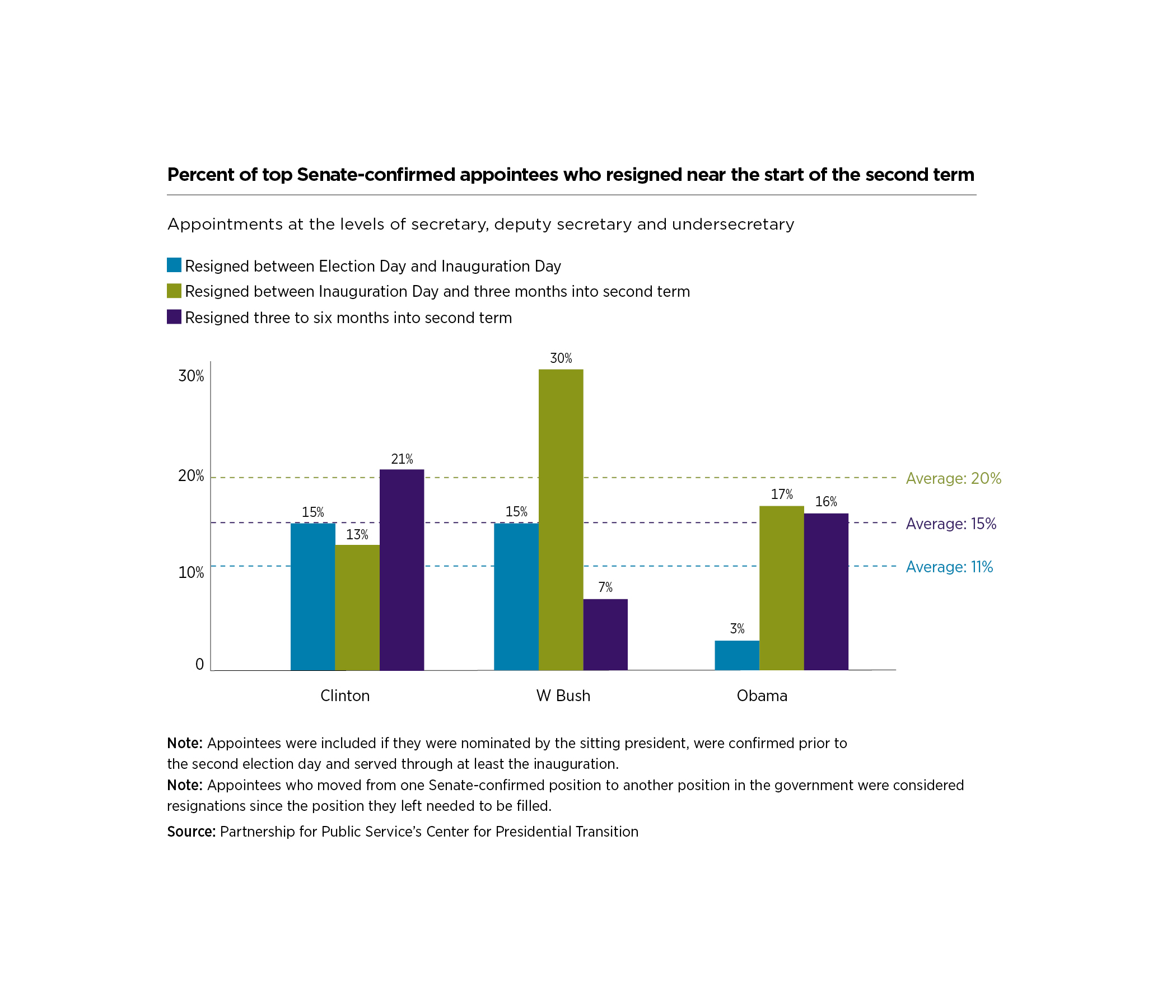

Data compiled by the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition shows that for the last three two-term presidents, an average of 46 percent of their top Senate-confirmed officials serving on Election Day left their jobs within six months into the second terms. These include Cabinet secretaries, deputy secretaries and undersecretaries. On average, 31 percent left within three months.

“This kind of turnover shows planning for the next four years is more important than you might think,” said McDonough, the former Obama White House chief of staff. “How you can build in time to make those kinds of decisions so they’re not coming at the expense of everything else you want to do in the second term is really important.”

The vast majority of the Cabinet secretaries, deputy secretaries and undersecretaries have been traditionally filled by presidents during their first year in office. However, presidents cannot expect those early appointees to serve deep into their administrations. For the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations, 76 percent of senior-level appointees served less than four years.

As for the White House staff, the jobs can be so exhausting that some aides may want to leave after the election. In such cases, the challenge may be how to encourage people to stay and how to maintain continuity.

White House offices of presidential personnel have previously developed retention and advancement strategies for appointees in less senior roles and at agencies. Often started in the first term, these programs can support retaining talent by identifying individuals interested in staying in the administration by moving to a new role or agency. During the Obama administration, for instance, White House liaisons coordinated with the Office of Presidential Personnel to bring individuals into new roles. In this manner, a core of appointees built cross-agency experience and supported leaders with an enterprise-wide mindset for policy implementation.

The president may have a clear sense of who should depart and the names of possible replacements, but the Office of Presidential Personnel, at the direction of the White House chief of staff, should develop a highly confidential short list of qualified people for every Cabinet post available for the president’s scrutiny. A list of high-performing individuals who could be promoted or given new responsibilities in the agencies and at the White House should also be developed, along with the names of campaign staff who may want to serve in the administration.

President George W. Bush had conversations about Cabinet changes with then-chief of staff Andy Card prior to his 2004 re-election and in a number of instances had made up his mind about who should be replaced and by whom, but that information was kept confidential to avoid distractions during the campaign.

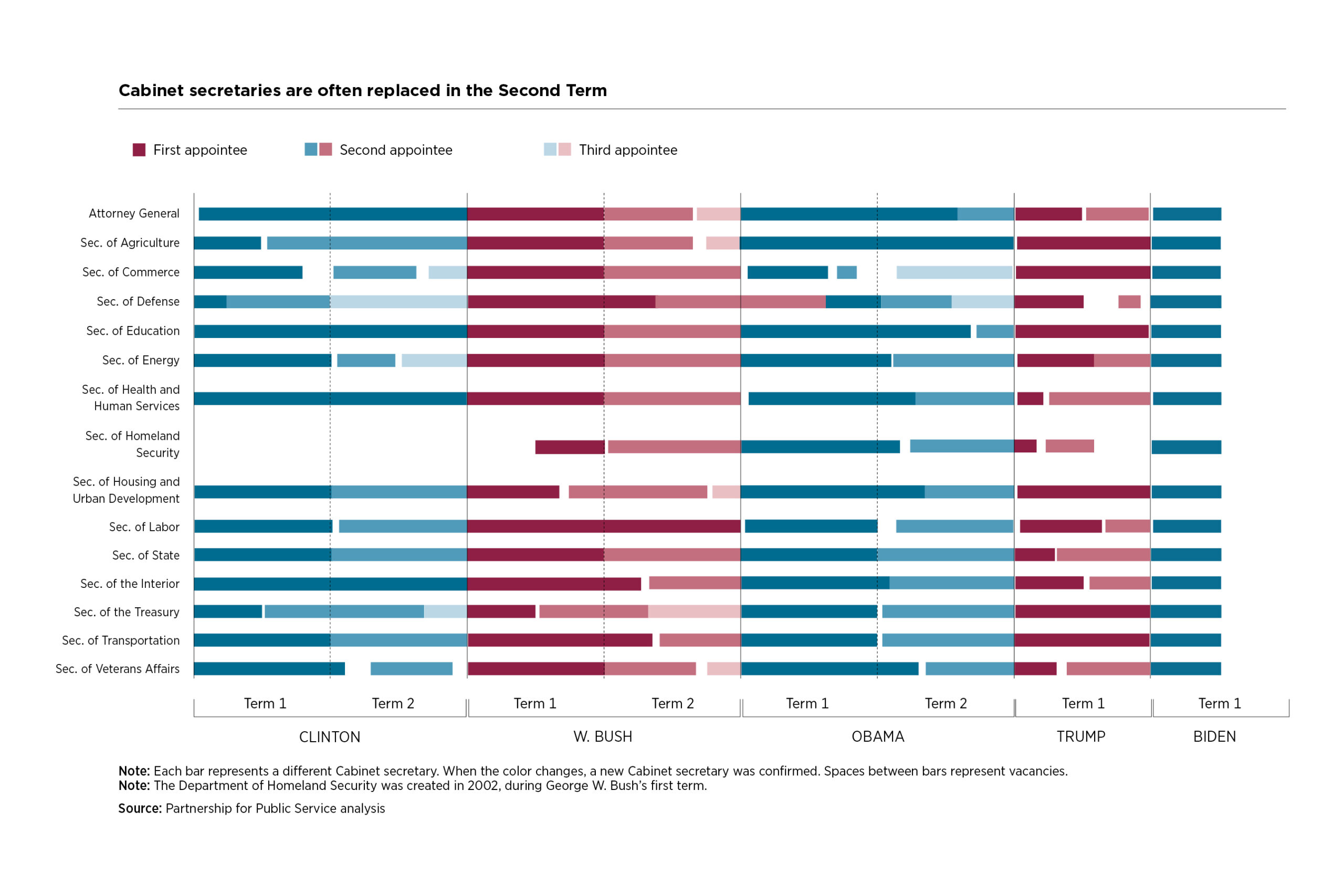

Obama waited until after the 2012 election, meeting with his Cabinet secretaries individually to determine whether they wanted to stay on the job. Both presidents ultimately experienced significant turnover among the Cabinet secretaries and their leadership teams, along with other political appointees.

During the period between the election and the early months of the second term, nine Cabinet secretaries departed the Bush administration and six left the Obama administration.

During the post-election phase, the president should act quickly to pick Cabinet replacements and other critical nominees, and coordinate with the Senate to expedite confirmation hearings and votes. Anticipating changes in agency leadership teams, the White House can prepare to train new political appointees using the $1 million authorized in statute for this purpose.

Congress provided resources to train incoming appointees in recognition that many come to their jobs without prior experience in government. Once this critical team is in place, a retreat for the president and members of the second-term Cabinet and senior White House staff will help build relationships and set a foundation for the next four years.

Convene White House and agency transition coordinating councils

Even when an incumbent president is running for re-election, the White House is still obligated by law to plan and coordinate activities to ensure a smooth and efficient transfer of power to a possible successor.

This includes convening the White House Transition Coordinating Council and the Agency Transition Directors Council to provide guidance on transition activities, and negotiating a memorandum of understanding with the challenger setting forth the terms of agency engagement and addressing ethics issues following the election. The law also requires the naming of a transition coordinator from the General Services Administration, who serves as the person responsible for ensuring that statutory requirements for transition planning and reporting by agencies are met and as a liaison to presidential candidates.

The law also directs that agency leaders appoint career executives as transition directors. These agency transition directors will lead agency efforts to provide new appointees with the information needed to be ready to govern.

Agency transition teams led by career executives must prepare just as they would at the end of an eight-year presidency, including developing comprehensive briefing materials and, after the election, offering full assistance to a president-elect’s transition landing teams and new political appointees. More information on this topic can be found in the next chapter.

Agency political leaders can play a pivotal role in second-term planning

While the career-led agency transition teams prepare briefing materials for a new administration prior to the election, the incumbent president should direct the political leaders at the major departments to develop separate materials for the White House focusing on how their organizations will contribute to advancing the president’s agenda during a second term. Thoughtful planning for a second term will allow both the White House and agency leaders to generate ideas and momentum. Agency political appointees are well-positioned to highlight important initiatives that should continue and be strengthened in a second term, offer new ideas that could be incorporated into a second-term agenda and provide information on the resources needed to achieve the various goals and the risks that must be managed.

In the past, presidents seeking re-election have not taken full advantage of the opportunity that a second term offers to review and improve policymaking, program effectiveness and management practices. While a second term in many respects represents a continuation of the previous four years, it offers a chance for a recalibration and a new start that requires serious planning and preparation long before Inauguration Day.