Home / Senate confirmation

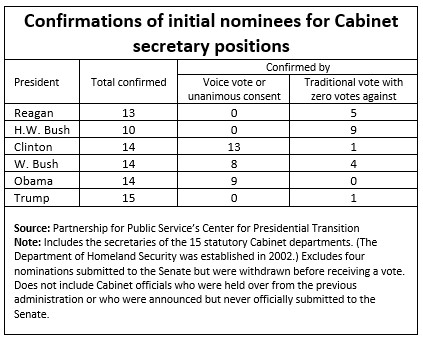

For Presidents Clinton, Bush and Obama, 71% of their initial Cabinet secretaries were confirmed by voice vote or unanimous consent

By Carlos Galina and Drew Flanagan

For new presidents, having Cabinet secretaries in place as soon as they take office is crucial to ensure the continuity of the government, especially during times of crisis. The Senate has understood the need for a new president to be ready to govern, giving recent incoming chief executives significant latitude by confirming their Cabinet choices quickly and often with little or no opposition.

Under Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, 71% of initial Cabinet secretaries confirmations were approved by the Senate using voice votes or unanimous consent agreements. Almost every initial Cabinet nominee during the past four decades has been approved, most facing little objection.

Voice votes and unanimous consent agreements are used by the Senate to advance legislation and confirmations quickly. Unlike most Senate votes, these procedures do not require individual senators to record their vote and are reserved for issues where there is a wide consensus and no doubt about the outcome. The extensive use of voice votes and similar agreements demonstrate how little congressional opposition recent presidents have faced regarding their first choices to head the executive departments.

The lack of Senate objections extends to the two administrations preceding Clinton as well. Even though the Senate did not use voice votes for the initial Cabinet nominations of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, votes against their picks were rare. Reagan’s choices were confirmed by an average margin of 90 votes, and five were approved unanimously. Furthermore, nine of the 10 of the Cabinet nominees confirmed under H.W. Bush were approved unanimously. The tenth, Secretary of Health and Human Services Louis Sullivan, was approved by a vote of 98-1.

President Donald Trump’s initial Cabinet nominees were more controversial than those of previous presidents and therefore faced more Senate opposition. None were confirmed by voice vote or unanimous consent. However, Trump’s experience represents the exception rather than the rule. Because Trump’s transition team leadership changed immediately following the 2016 election, Trump had a late start identifying and vetting candidates. Even with the delays, the Senate generally gave Trump the leeway to choose members of his Cabinet. All 15 Cabinet secretaries who received a Senate vote were confirmed, with nine of those receiving at least 60 votes. Trump’s initial choice for Labor Department secretary, Andy Puzder, was submitted to the Senate, but withdrew before receiving a vote.

As President-elect Joe Biden prepares to enter office, the Senate will soon consider his choices for important leadership roles. The frequent use of voice votes during the past 40 years demonstrates how the Senate can support the transition process by confirming Cabinet choices quickly. A return to this historical precedent would help ensure the Biden administration is prepared to manage the significant challenges currently facing our country.

Filling key health-related positions was not a priority during recent presidential transitions. By their 100th day in office, only 28% were filled under Trump and 35% under Obama.

By Christina Condreay

As medical professionals and essential workers begin to receive the coronavirus vaccine, the nation enters a new phase of the pandemic. Yet even with this positive development, the country faces thousands of deaths from the virus each day and will likely be dealing with the pandemic for months to come. With the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden only days away, the new administration will need key health officials in place quickly to coordinate the government’s response and assure continuity during the change in leadership.

Biden’s plan for a COVID-19 response includes providing 100 million vaccines in 100 days and reopening schools safely by May. To achieve these goals, he must have personnel in key decision-making positions. Recent history, however, shows that under the last two presidents, most health-focused jobs were not among the earliest filled. In fact, under Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama, only about one-third of leadership positions responsible for coordinating health efforts were confirmed by the Senate within 100 days of taking office.

To study the priority given to these roles, the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition identified 50 Senate-confirmed positions relating to public health and emergency response. The list is comprised of positions held by individuals on the current coronavirus task force, health-related nominees already announced by Biden and the positions of those who participated in the 2016 transition pandemic tabletop exercises. Additionally, the Center examined job descriptions for more than 400 positions across 22 agencies. The final list of 50 includes agency heads and Cabinet department secretaries, as well as assistant and undersecretaries responsible for less visible but important agency subcomponents.

Pandemic response positions during the Trump administration

Of these 50 key positions, only 14 were filled during the first 100 days of the Trump administration (28%). When the pandemic began in early 2020 – and Trump had been in office for three years – only 28 of these 50 positions or 56% were filled with a Senate-confirmed official. Even though the Senate confirmed these officials, significant turnover occurred during Trump’s first three years. Between Inauguration Day and March 1, 2020, 20 Senate-confirmed officials in pandemic response positions had resigned.

The lack of Senate-confirmed officials was due in part to Trump’s slow pace of nominations. During Trump’s first year in office, he submitted nominees for just 27 of the selected positions. In his second year, Trump submitted nominations for only 11 more. Another cause of the delays was the length of time it took the Senate to vote on nominations.

All told, 42 of the 50 health-related positions were filled at some point during the Trump presidency, even if not by the start of the pandemic. On average, the Senate took 99 days to confirm those nominations.

Pandemic response positions during the Obama administration

The Obama administration filled a few more of these health-related jobs early in its first year, but only by a small margin. During the first 100 days, 35% of these positions had a Senate-confirmed official, including four holdovers from President George W. Bush’s administration. There was a notable difference, however, in staffing these positions during Obama’s second year. By the end of Obama’s second year in office, the administration had sent nominations for 39 of the 50 positions to the Senate.

Due to key holdovers from the Bush administration and five recess appointments, a permanent official served in 49 of the health-related positions by the end of Obama’s third year. The Trump administration added a Senate-confirmed position, the director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, which is included in our list. On average, the Senate took 71 days to confirm officials for those positions during the Obama administration.

Conclusion

An effective strategy to fight the pandemic requires a smooth transition of power and continuity in leadership. Although many health-related positions were not filled quickly during the last two administrations, the Senate and Biden administration have a joint obligation to expeditiously nominate and confirm officials for these critical roles to deal with the current crisis.

This week’s episode of Transition Lab focuses on the Senate confirmation process with Phil Schiliro and Candi Wolff.

Wolff, the head of global government affairs at Citi, served as the Assistant to the President for Legislative Affairs under President George W. Bush. She was the first woman to hold that position. Schiliro worked on Capitol Hill for nearly three decades before serving as congressional liaison for the 2008 Obama transition and director of legislative affairs for the Obama White House. He helped pass numerous laws during his long career, including the 1990 Clean Air Act and the Affordable Care Act.

In this episode, host David Marchick speaks with Schiliro and Wolff about how legislative affairs teams help move presidential nominees through the Senate, the slow Senate confirmation process and how President-elect Biden might manage his relationship with the Senate in 2021.

[tunein id=”t159829396″]

Read the highlights:

Schiliro described working in the White House Office of Legislative Affairs.

Schiliro: “To do the job right, you have to be saying ‘no’ to Congress a lot during the day and then, in the late afternoon, come back to the White House and tell White House staff ‘no’ on what they want Congress to do. …People on both sides are tired of you saying ‘no.’ …I don’t think there’s another office in the White House that is as involved [in Congress] as the Office of Legislative Affairs because virtually everything the president does touches on Congress.”

Schiliro explained why the Senate confirmation process takes so long.

Schiliro: “Each nominee goes through a vetting process ahead of time, but there’s a second vetting process after the person’s nominated. …One of the big issues becomes prioritizing the nominees after the Cabinet. People on Capitol Hill may have different views than people in the White House on what that sequence is going to be. …There’ll be committees that have to do hearings for multiple nominees, so you’re stretching the committees to capacity. Then there’s the problem of floor time. …The White house will have priorities [and] the Senate leadership will have different priorities. …And [sometimes] nominees become pawns for a policy dispute, [leading] senators to put holds on nominees. …When you add all that together, it ends up being a very complicated, lengthy process.”

Schiliro and Wolff described how increased partisanship has affected the Senate confirmation process.

Schiliro: “There’s always been partisanship, but some of the norms that used to be in place have slowly eroded over time. …We had a situation that bothers me because she was a friend of mine. Cassandra Butts, who was President Obama’s nominee to be ambassador to the Bahamas, had a hearing in May 2014. But then holds were put on her by two senators. She waited over 800 days for a vote and she died during that process. …One senator put a hold on her because he objected to the Iran nuclear deal. Another senator was upset about something that he thought President Obama did, knew he was friends with Cassandra and put a hold on her to inflict pain on the president.”

Wolff: “Members on both sides of the aisle feel like they can just hold up the nominees for unrelated reasons, not because of the qualification or their ability to do the job. …You have to have the team and the people who can work off the holds and figure out if you can come up with a solution. It’s incredibly frustrating.”

Schiliro and Wolff discussed how the Georgia runoffs might affect the Biden administration’s pre-inaugural political appointment work.

Wolff: “The process is going to be slow because we have to wait for the results in Georgia. And then after that, you have to have the two leaders meet to determine who’s on the committees. All of those processes have been put on hold. Normally they would be completed in December. …Right now, the Biden team can’t begin those discussions. And is the ratio [of Republicans to Democrats in the Senate] 50-50? Unfortunately, [these factors] will initially slow the process.”

Schiliro: “Layered on top of that is the coronavirus pandemic, which is impacting the ability of senators to actually be in Washington. Ideally, we’ll know the results in Georgia quickly, but if they’re close races, that could take four, five or six days, and the Senate will be in limbo during that period. …I would expect a slower process for any nominee that’s not a consensus nominee.”

Wolff explained why the COVID-19 pandemic might lead to faster Senate confirmations.

Wolff: “Crises tend to drive action. I see the pandemic as a driver that will focus attention on the Department of Health and Human Services. The Biden team can make the point that to get the vaccines approved, to get the distribution done, to deal with the health crisis, you have to have someone at HHS. [This] should result in a faster confirmation process.”

Wolff and Schiliro described their proudest moments in the White House and biggest legislative accomplishments.

Wolff: “It was a privilege to work [in the White House], provide public service and support the American people. …The legislation that I’m most pleased with is when one of the last trade agreements that got through. I remember that passing with one vote in the House and feeling really good about knowing where the vote count was going to be.”

Schiliro: “It was a combination of things—trying to give the president a realistic, accurate assessment as we were developing strategies of what would work and what wouldn’t work, and having a team at the White House Office of Legislative Affairs that was just terrific. …If I had to pick a piece of legislation, it was the Affordable Care Act because it meant so much to the president, it was difficult to do and we had to navigate so many problems.”

Almost half of key national security positions requiring Senate confirmation were vacant on 9/11/2001

By Alex Tippett

A transition to a new presidential administration is a unique moment of vulnerability for our country. As President-elect Joe Biden selects his full national security team and the Senate prepares to consider presidential appointments, the experiences of previous transitions serve as cautionary tale for why slow nominations and lengthy confirmation processes can leave the nation vulnerable.

The most prominent example of how a prolonged confirmation process can undermine national security is the terrorist attacks of the Sept. 11, 2001, which occurred about eight months into President George W. Bush’s first year in office. At that time, many national security positions were vacant due in part to the shortened transition period after the contested 2000 election and the challenges associated with getting officials into Senate-confirmed positions.

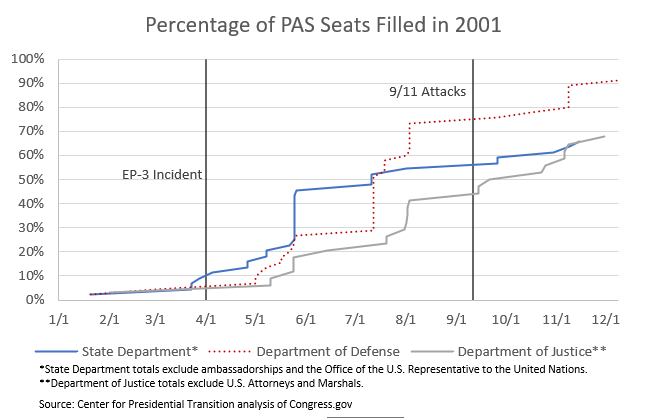

At the time of the attacks, only 57% of the 123 top Senate-confirmed positions were filled at the Pentagon, Department of Justice and Department of State combined excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys. Of those officials who were in place, slightly less than half (45%) had been confirmed within the previous two months.

The bipartisan 9/11 Commission, which reviewed the causes of the attacks and its consequences, focused on the impact of the slow confirmation process. The commission suggested that delays could undermine the country’s safety, arguing that because “a catastrophic attack could occur with little or no notice, we should minimize as much as possible the disruption of national security policymaking during the change of administrations by accelerating the process for national security appointments.”

While Congress implemented a number of the commission’s recommendations, the nomination process continues to be a liability and underlines the importance of moving swiftly to confirm qualified nominees.

Confirming the Bush National Security Team

Most of Bush’s leadership at the Department of Defense took months to get into place. While Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was confirmed on Jan. 20, 2001 and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, was confirmed in late February and no other member of the DOD’s leadership team was confirmed until May.

It was during this period that the Bush administration faced its first major national security test. On April 1, 2001, a Navy surveillance plane collided with a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea. The Chinese pilot was killed in the collision and the American crew was taken into captivity. Over the next 11 days, a tense standoff ensued. While the crisis was eventually brought to a peaceful close, Wolfowitz and Rumsfeld were the only Senate-confirmed members of Bush’s DOD team, with the third and fourth ranking appointees confirmed on May 1, 2001—a full month after the incident began.

By the time of the 9/11 attacks, the Senate had confirmed a total of 33 DOD officials. Two-thirds of those officials had been on the job for less than two months. According to the 2000 Plum Book, there were 45 positions at DOD requiring Senate confirmation, leaving 12 important jobs empty on 9/11.

In an interview with the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, Stephen Hadley, Bush’s deputy national security advisor, suggested the slow pace of nominations undermined the administration’s ability to develop a response to the threat posed by the al-Qaeda terrorist group responsible for 9/11. “When people say, ‘Well, you had nine months to get an alternative strategy on al-Qaeda,’ no, you didn’t. Once people got up and got in their jobs you had about four months.”

Empty seats and a slow nomination process also hurt other parts of the Bush administration. Michael Chertoff, who served as head of the Department of Justice’s criminal division on 9/11, recalled, “We were shorthanded in terms of senior people….we essentially had to do double and triple-duty to pick up some of the responsibilities that would have been taken by others who were confirmed.”

Following a bitter five-week struggle, John Ashcroft was confirmed as attorney general on Feb. 1, 2001. His deputy, Larry Thompson, was confirmed on May 10, along with Assistant Attorney for Legislative Affairs Daniel Bryant.

Excluding U.S. marshals and attorneys, DOJ had 34 Senate-confirmedpositions in 2000. But Just 41% of those jobs were filled on 9/11. Half of those 14 officials—including then FBI Director Robert Mueller–were on the job less than two months before the attacks.

Bush’s State Department, supported by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, moved faster than other committees in the early days of the administration, but then slowed its pace. Before June, the State Department filled 20 of 44 Senate-confirmed positions, excluding ambassadorships. On 9/11, just 24, or 55%, of the 44 positions at the State Department were filled.

Conclusion

In light of these delays, the 9/11 commission recommended that, “A president-elect should submit the nominations of the entire new national security team, through the level of undersecretary of Cabinet departments, not later than January 20. The Senate, in return, should adopt special rules requiring hearings and votes to confirm or reject national security nominees within 30 days of their submission.”

Both the Senate and the Biden team should work to meet this standard. And while the Senate should carefully scrutinize every nominee, it also should recognize that unnecessary delays could undermine the ability of the new administration to respond to the threats we currently face and those that are unexpected.

Chief financial officers play an essential role in the stewardship of the federal government’s resources, guiding agency finances, strengthening the capability of the workforce, meeting customer needs and using new technologies to improve payment accuracy. As we approach the 30-year anniversary of the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, there have been continual improvements of financial management systems and audits, and greater use of technology and data to increase the government’s ability to make informed decisions.

While CFOs have played an essential part in these developments, challenges remain. The role of the CFO has not been updated since the 1990 legislation. Many agencies are still working to implement core elements of the statute, and several agencies remain out of compliance with the law’s technical requirements.

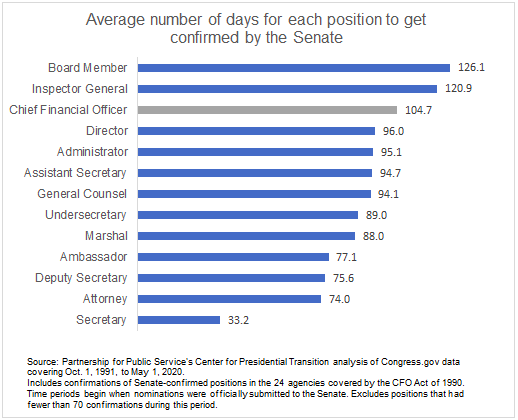

Another challenge has been the low priority given to CFOs by the Senate. One indication is the amount of time the Senate takes to confirm CFO appointees. For the nearly three-decades since the CFO law was enacted, the Senate has taken an average of 104.7 days to confirm CFOs. That is the third-longest average for any type of job within these agencies behind only inspectors general and members of various government boards.

A recent report produced by the Partnership for Public Service and Deloitte, “Finance of the Future,” made recommendations to modernize the role of CFO. One recommendation called for standardizing the position government-wide by delineating a common set of core responsibilities. This would enhance their ability to integrate and share information across agencies, transfer institutional knowledge and standardize functions.

Another recommendation called for improved continuity in CFO leadership. Currently, 15 of 24 federal CFOs are Senate-confirmed positions while the others are career positions. Congress should consider converting all CFO jobs to career positions or establishing the role as a fixed term with a performance contract. In that situation, CFOs would be expected to remain in office even with a change in administration.

Many of these recommendations are contained in a bipartisan bill proposed by Sens. Mike Enzi, R-Wyo. and Mark Warner, D-Va.

To meet the evolving needs of federal financial management, the Senate and agencies should make changes to better position CFOs to fulfill their obligations to the American people.

Editorial credit: Katherine Welles / Shutterstock.com

By Bruce Andrews

This post is part of the Partnership’s Ready to Serve series. Ready to Serve is a centralized resource for people who aspire to serve in a presidential administration as a political appointee.

The opportunity to serve in a presidentially-appointed position in the federal government is a unique privilege and honor. For some positions, this means nominees must traverse the difficult Senate confirmation process before they can take office.

The confirmation process can be one of the biggest challenges a nominee will face in their lifetime. The process puts the fate of a highly accomplished individual in the hands of a Senate committee and a small group of staff, followed by the full Senate for a vote. Rarely do nominees depend so heavily on the judgment of others.

I had the opportunity to work on several sides of the process— first overseeing nominations for the Senate Commerce Committee as the general counsel, then helping nominees navigate the process as chief of staff of the Commerce Department, and finally working on my own nomination to be deputy secretary of Commerce. Here’s some advice for navigating the process.

Tip 1: Be honest

Nominees rarely know how intrusive the process will be and how deeply the background check and the committee will get to know them. In my experience, it is most important to be fully transparent and honest. It is always better to disclose everything, even embarrassing information, rather than be seen as untruthful or misleading.

Tip 2: Trust your team

Remember that confirmation is a team sport! Nominees need champions to build support and to work with potential critics.

The good news is that nominees have a confirmation team to help them. Trust the team. They are experts and their job is to help get the nominee confirmed. They are selected for their understanding of the process and have many resources to draw from.

Tip 3: Think about relationships

Prior to confirmation, nominees should catalogue their relationships and identify third party validators.

When thinking about relationships, some key questions to ask include:

- Which senators do you know?

- Do you have friends who know key senators?

- Do you have people who can vouch for the nominee?

- Can your home state senators help?

When I went through confirmation, I thought I would be fine with Democrats, but wanted to strengthen my support among Republicans. I was fortunate to have a group of well-connected Republicans who served as my “Shadow Confirmation Team.” They enthusiastically helped me by reaching out to key Republican senators, committee and leadership staff. Not everyone is as fortunate to have that kind of assistance, but all nominees will benefit from examining their own networks for potential help.

A crucial step in the process involves meetings with members of the Senate committee that has jurisdiction over the position you are seeking. These meetings may be with senators or their senior staff. They are the best way for nominees to introduce themselves, learn about the important issues from each committee member and earn their support.

Tip 4: Remember the hearing is part interview and part political theater

Next, the confirmation hearing will be scheduled. The hearing is not just an opportunity for the nominee to answer questions, but also for senators to impress on the nominee what they see as most important and show their constituents they are fighting for them. If senators want to spend three of their allotted five minutes talking about their positions, that is great. It is less time for the nominee to have to answer questions.

During my hearing, one senator asked me to come meet the fishermen in her state. I first suggested they meet with the regional official as instructed by my confirmation team. She then asked a second time, and I repeated the crafted response. On the third time she pressed me, I finally agreed to visit her state. (After the hearing, my eight-year-old daughter asked why I didn’t just agree when she asked in the first place.) After I was confirmed, my team reached out to her office to schedule a trip to meet with the fishermen, but her office never followed up.

Tip 5: Only answer the question that is asked

Many nominees want to show how smart they are. The most important thing is to listen to what the committee members are asking, and do not go beyond the question. Many nominees get in trouble by straying off topic.

I will never forget one hearing I staffed when a nominee violated this rule and tried to answer questions that were not asked to show the breadth of his knowledge. His responses raised concerns from several senators and led to an entirely new set of tougher questions. No one should want to be that nominee.

The confirmation process is not always easy, but it is a time-honored part of our democracy. Serving your country is an incredibly rewarding experience, but it is important to respect the crucial role of the Senate in that process, and preparing wisely will increase the chance for a successful confirmation.

Bruce Andrews is managing partner at SoftBank Group and a former deputy secretary for the U.S. Department of Commerce. He also served as general counsel to the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee.

By Paul Hitlin

Temporary leaders – commonly referred to as acting officials – have been used by all recent administrations to fill important positions atop federal agencies. Many questions surround their use and power. How long can acting officials serve? Who is eligible? What happens when the time limit for an acting official runs out? Most of the rules are governed by the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998. However, the law gives presidents a fair amount of flexibility and many details are open to interpretation.

Little research exists on the subject,

but a new scholarly article examines the issue in depth and provides important

considerations and recommendations. The piece by Anne Joseph O’Connell of Stanford

Law School published in the Columbia Law

Review includes data from 1981 through President Trump’s third year in

office, and discusses many impacts of temporary leadership.

Among the major findings:

- President Trump has utilized significantly more

acting Cabinet secretaries than prior presidents.

- Previous presidents relied on temporary leaders,

particularly at the start and end of administrations.

- Without Senate confirmation, temporary officials

may lack external buy-in from Congress and the White House.

- Not all impacts of temporary officials are

negative. For example, temporary leaders seeking the permanent job may provide

the Senate with an audition.

O’Connell offers recommendations for clarifying the Vacancies Reform Act.

- Congress should remove ambiguities in the

Vacancies Reform Act to “discourage end runs around the normal appointments

process.”

- The law should include agency-specific

succession provisions.

- The law should address presidential firings.

- The law should specify that for officials to

qualify as a first assistant – and thus be eligible to serve as an acting role

– they must be named before the vacancy arises.

- The law should address whether the mandates

about qualifications and removal for confirmed officials apply to temporary

officials.

O’Connell points out that acting officials have become a fixture of modern presidencies despite receiving little attention, and that Congress has abdicated some of its advise and consent role by accepting increased reliance on interim leadership. To balance concerns over accountability and the need for the government to function, O’Connell argues that it is time for Congress to clarify the rules governing the use of acting officials.

By Jaqlyn Alderete

The Senate now takes 115 days on average to confirm presidential appointees, twice as long as during the Reagan administration.[1] Given the length of time it can take to get nominees confirmed, a new administration or second-term administration must prepare to face the reality of having vacant positions and identify their options for filling those roles.

In the beginning of a new administration, it is common for most presidentially appointed Senate-confirmed positions to be filled by acting officials while the nomination and confirmation process plays out. Second-term administrations typically experience significant turnover in critical leadership roles following re-election. According to the Center for Presidential Transition’s report on turnover during the previous three administrations, 43% of key leadership positions were left vacant within six months of the start of a president’s second term, either by personal choice or because the president wanted a change and fresh ideas. Given the high turnover rate, second-term administrations must plan for how they will fill these roles while waiting for the Senate confirmation process to play out.

The Federal Vacancies Reform Act outlines limitations to who can serve in acting roles and for how long. Under the Vacancies Act, there are three types of officials who may carry out the duties of the vacant position in an acting capacity without Senate confirmation.

- The “first assistant,” interpreted to be the top deputy position, becomes the acting officer unless the president designates another individual from the other two eligible classes of officials. The Vacancies Act does not specifically define “first assistant.”

- The president may designate an individual who serves in another presidentially appointed, Senate-confirmed position elsewhere in the federal government as the acting official.

- The president may designate a senior employee of the same agency as the acting official if that person has served in the agency for at least 90 days during the year preceding the vacancy and is paid at a rate equivalent to at least a GS-15.

The Vacancies Act limits an individual serving in an acting role for 210 days. However, this period is lengthened to 300 days if a vacancy exists on the new president’s inauguration day or occurs within 60 days after the inauguration.

While these all are helpful ways to manage vacancies, they are temporary placeholders for long-standing leadership positions, as acting officials lack the authority that comes with a presidential appointment and Senate confirmation process. It is imperative that administrations develop efficient procedures for sending nominees to the Hill and that they prepare to manage vacancies within the limits of the Vacancies Act.

[1]

Center for Presidential Transition, “Senate Confirmations Process Slows to a

Crawl,” Jan. 2020. Available at https://presidentialtransition.org/publications/senate-confirmation-process-slows-to-a-crawl/

By Kristine Simmons and Kayla Shanahan

America is “big” by most measures, from the size of our population and land mass, to the boldness of our ideas and our global influence. The challenges facing our government are big too. Delivering services to over 300 million Americans and leading the free world require great talent and exceptional leaders in public service.

The opportunity to serve the American people is an honor, and

those in Senate-confirmed presidential appointments assume some of the toughest

jobs in government. They oversee

billions of dollars in federal spending and thousands of employees, are

accountable to the president and to Congress and work under the scrutiny of the

public and the media. It is challenging work, but uniquely rewarding; many

current and former federal leaders say that public service is both the hardest

and the best professional experience of their careers. Few opportunities exist outside of government

to work with the best and brightest minds on a mission that matters to

thousands – and even millions – of people at home and around the world.

The public benefits when individuals from diverse backgrounds and

experiences use their talents for the public good – so it should be easy for

those who want to serve to do so.

Unfortunately, it’s not. The appointments process is difficult to

navigate even for experienced government insiders; for individuals who are

coming from academia, the private or nonprofit sectors, it is baffling. Government loses out when the process discourages

people with needed expertise, new perspectives on long standing problems, and solutions

from outside of the public sector from serving.

The appointment process for Senate-confirmed positions is longer,

more public, and more onerous than ever. To date, 63 of

President Trump’s nominees have removed themselves from consideration or had

their nominations withdrawn, and some previously interested and highly

qualified individuals will no longer consider a presidential appointment. Why?

- Long wait

time to start position: Most prospective appointees are expected to

leave their pre-nomination jobs in the time between their nomination and

confirmation, even when confirmation is not guaranteed and a start date is

unknown. Though most nominees will eventually make it through the process – historically,

the Senate confirmed over 98% of Cabinet appointees – the length

of time from nomination through confirmation continues to increase, often for

reasons unrelated to the nominee. In 2019, the

average confirmation process lasted 136 days – limiting the pool of prospective

candidates to only those who are willing and able to forego income for long

stretches of time.

- Arduous

vetting process with limited support: Positions of

public trust require a rigorous vetting process, and appropriately so. But the process as it exists today is complicated

by the risk of innocent mistakes and missteps. Candidates must complete hundreds of

pages of paperwork with questions on their background, health, financial

holdings, and personal life. The online

form SF-86 for

background investigations is 127 pages, and just one of the forms required

of nominees. While it is critical to vet candidates thoroughly, expectations

seem out of step with the lives that many senior leaders live today. For

example, prospective candidates must report the date of every encounter with a

foreign associate going back five, ten or fifteen years, and sometimes all the

way back to age 18. In today’s globalized world it is unrealistic to expect

individuals to recall and document every interaction with a foreign associate

years later. As a result, many candidates incorrectly complete or simply cannot

accurately complete the necessary paperwork.

- Financial

implications for candidates: Candidates must provide highly detailed

information about their financial holdings, tax filings, and business dealings.

Many hire accountants and private attorneys out-of-pocket just to compile the

necessary paperwork. Once their financials are reviewed, candidates and their

families often are forced to divest assets of significant value, even though

the candidate will likely only serve in that capacity for a short tenure. Several

post-service obligations may further deter prospective appointees.

- Highly

publicized process for candidates and their families: Media

coverage of executive branch appointments is higher than ever. While public

officials expect to be in the spotlight, privacy no longer extends to their family

members, who remain private citizens. Nominees endure public scrutiny, often at

the professional and personal expense of themselves and their families.

Recruiting America’s top talent is critical to delivering a more

effective government to the American people. The Partnership for Public Service continues research

on the pain points of the appointment process, providing recommendations for improvements

to ensure that talented Americans are not deterred from serving our country as

a presidential appointee.