Home / Political Appointments

By Bishop Garrison

This post is part of the Partnership’s Ready to Serve series. Ready to Serve is a centralized resource for people who aspire to serve in a presidential administration as a political appointee.

The chance to work in a presidential administration is an experience like no other, offering a unique opportunity to serve the nation and its citizens.

From my experience in various positions during President Barack Obama’s administration, I gained insights into issues candidates should consider when deciding whether to pursue a political appointment. The following advice will help you decide if a presidential appointment is right for you.

Before accepting a position, ask yourself about your motivation to join and if now is the right time to serve.

An offer to serve your country can be one of the highest honors of an individual’s professional life. Securing such a position is a competitive process and can lead to more prestigious jobs in the future. However, there is a thin line between a true desire to serve and an interest in furthering your career. If you are offered a political appointment, make sure you are accepting it for the right reasons. Ensure it is the right fit for your own interests and career. You will need to give your all every day, so make sure it’s a position that can make you happy.

If you accept a position, seek out new challenges that may not have been part of your original career goals.

A presidential appointment will lead to opportunities for professional development and for learning new skills. When circumstances allow, seek out new challenges, especially ones you did not anticipate. Many of the best opportunities to grow will come from tasks outside of your primary responsibilities. It may be supporting a project in another directorate serving as an extra pair of hands or joining optional professional development sessions. There is no one true path to success, and exploring less obvious avenues will provide unexpected, yet rewarding experiences.

Prepare for difficult times and view them as opportunities to learn and grow.

Former Secretary of State Colin Powell once said, “All work is admirable.” While Powell’s statement rings true, not every part of your job will be like the inspiring television episodes of The West Wing or Madam Secretary. There will be times of exhaustion and frustration, but they can be buoyed by the opportunity to accomplish important work and rebuild faith in our government. Meet with your career colleagues and learn from them. They can provide a wealth of knowledge based on their varied experiences. They understand these institutions intimately and what it will take to engage the public through smart, thoughtful policy and action.

The Bottom Line

Before accepting a political appointment, make sure you consider all potential factors that may affect you, such as personal motivation, work-life balance, financial concerns and the demands of the position. Many appointees do not think about these questions until it is too late, and they should play a role in in whether to accept a presidential appointment.

At the end of the day, however, serving in a presidential administration is an honor and a unique opportunity to make a difference. Whatever you choose, ensure it is the right decision for you.

Bishop Garrison served in various national security positions in the Obama administration and as deputy foreign policy adviser for the 2016 Hillary Clinton campaign. He is currently director of national security outreach for Human Rights Watch.

Filling key health-related positions was not a priority during recent presidential transitions. By their 100th day in office, only 28% were filled under Trump and 35% under Obama.

By Christina Condreay

As medical professionals and essential workers begin to receive the coronavirus vaccine, the nation enters a new phase of the pandemic. Yet even with this positive development, the country faces thousands of deaths from the virus each day and will likely be dealing with the pandemic for months to come. With the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden only days away, the new administration will need key health officials in place quickly to coordinate the government’s response and assure continuity during the change in leadership.

Biden’s plan for a COVID-19 response includes providing 100 million vaccines in 100 days and reopening schools safely by May. To achieve these goals, he must have personnel in key decision-making positions. Recent history, however, shows that under the last two presidents, most health-focused jobs were not among the earliest filled. In fact, under Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama, only about one-third of leadership positions responsible for coordinating health efforts were confirmed by the Senate within 100 days of taking office.

To study the priority given to these roles, the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition identified 50 Senate-confirmed positions relating to public health and emergency response. The list is comprised of positions held by individuals on the current coronavirus task force, health-related nominees already announced by Biden and the positions of those who participated in the 2016 transition pandemic tabletop exercises. Additionally, the Center examined job descriptions for more than 400 positions across 22 agencies. The final list of 50 includes agency heads and Cabinet department secretaries, as well as assistant and undersecretaries responsible for less visible but important agency subcomponents.

Pandemic response positions during the Trump administration

Of these 50 key positions, only 14 were filled during the first 100 days of the Trump administration (28%). When the pandemic began in early 2020 – and Trump had been in office for three years – only 28 of these 50 positions or 56% were filled with a Senate-confirmed official. Even though the Senate confirmed these officials, significant turnover occurred during Trump’s first three years. Between Inauguration Day and March 1, 2020, 20 Senate-confirmed officials in pandemic response positions had resigned.

The lack of Senate-confirmed officials was due in part to Trump’s slow pace of nominations. During Trump’s first year in office, he submitted nominees for just 27 of the selected positions. In his second year, Trump submitted nominations for only 11 more. Another cause of the delays was the length of time it took the Senate to vote on nominations.

All told, 42 of the 50 health-related positions were filled at some point during the Trump presidency, even if not by the start of the pandemic. On average, the Senate took 99 days to confirm those nominations.

Pandemic response positions during the Obama administration

The Obama administration filled a few more of these health-related jobs early in its first year, but only by a small margin. During the first 100 days, 35% of these positions had a Senate-confirmed official, including four holdovers from President George W. Bush’s administration. There was a notable difference, however, in staffing these positions during Obama’s second year. By the end of Obama’s second year in office, the administration had sent nominations for 39 of the 50 positions to the Senate.

Due to key holdovers from the Bush administration and five recess appointments, a permanent official served in 49 of the health-related positions by the end of Obama’s third year. The Trump administration added a Senate-confirmed position, the director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, which is included in our list. On average, the Senate took 71 days to confirm officials for those positions during the Obama administration.

Conclusion

An effective strategy to fight the pandemic requires a smooth transition of power and continuity in leadership. Although many health-related positions were not filled quickly during the last two administrations, the Senate and Biden administration have a joint obligation to expeditiously nominate and confirm officials for these critical roles to deal with the current crisis.

This week’s episode of Transition Lab focuses on the Senate confirmation process with Phil Schiliro and Candi Wolff.

Wolff, the head of global government affairs at Citi, served as the Assistant to the President for Legislative Affairs under President George W. Bush. She was the first woman to hold that position. Schiliro worked on Capitol Hill for nearly three decades before serving as congressional liaison for the 2008 Obama transition and director of legislative affairs for the Obama White House. He helped pass numerous laws during his long career, including the 1990 Clean Air Act and the Affordable Care Act.

In this episode, host David Marchick speaks with Schiliro and Wolff about how legislative affairs teams help move presidential nominees through the Senate, the slow Senate confirmation process and how President-elect Biden might manage his relationship with the Senate in 2021.

[tunein id=”t159829396″]

Read the highlights:

Schiliro described working in the White House Office of Legislative Affairs.

Schiliro: “To do the job right, you have to be saying ‘no’ to Congress a lot during the day and then, in the late afternoon, come back to the White House and tell White House staff ‘no’ on what they want Congress to do. …People on both sides are tired of you saying ‘no.’ …I don’t think there’s another office in the White House that is as involved [in Congress] as the Office of Legislative Affairs because virtually everything the president does touches on Congress.”

Schiliro explained why the Senate confirmation process takes so long.

Schiliro: “Each nominee goes through a vetting process ahead of time, but there’s a second vetting process after the person’s nominated. …One of the big issues becomes prioritizing the nominees after the Cabinet. People on Capitol Hill may have different views than people in the White House on what that sequence is going to be. …There’ll be committees that have to do hearings for multiple nominees, so you’re stretching the committees to capacity. Then there’s the problem of floor time. …The White house will have priorities [and] the Senate leadership will have different priorities. …And [sometimes] nominees become pawns for a policy dispute, [leading] senators to put holds on nominees. …When you add all that together, it ends up being a very complicated, lengthy process.”

Schiliro and Wolff described how increased partisanship has affected the Senate confirmation process.

Schiliro: “There’s always been partisanship, but some of the norms that used to be in place have slowly eroded over time. …We had a situation that bothers me because she was a friend of mine. Cassandra Butts, who was President Obama’s nominee to be ambassador to the Bahamas, had a hearing in May 2014. But then holds were put on her by two senators. She waited over 800 days for a vote and she died during that process. …One senator put a hold on her because he objected to the Iran nuclear deal. Another senator was upset about something that he thought President Obama did, knew he was friends with Cassandra and put a hold on her to inflict pain on the president.”

Wolff: “Members on both sides of the aisle feel like they can just hold up the nominees for unrelated reasons, not because of the qualification or their ability to do the job. …You have to have the team and the people who can work off the holds and figure out if you can come up with a solution. It’s incredibly frustrating.”

Schiliro and Wolff discussed how the Georgia runoffs might affect the Biden administration’s pre-inaugural political appointment work.

Wolff: “The process is going to be slow because we have to wait for the results in Georgia. And then after that, you have to have the two leaders meet to determine who’s on the committees. All of those processes have been put on hold. Normally they would be completed in December. …Right now, the Biden team can’t begin those discussions. And is the ratio [of Republicans to Democrats in the Senate] 50-50? Unfortunately, [these factors] will initially slow the process.”

Schiliro: “Layered on top of that is the coronavirus pandemic, which is impacting the ability of senators to actually be in Washington. Ideally, we’ll know the results in Georgia quickly, but if they’re close races, that could take four, five or six days, and the Senate will be in limbo during that period. …I would expect a slower process for any nominee that’s not a consensus nominee.”

Wolff explained why the COVID-19 pandemic might lead to faster Senate confirmations.

Wolff: “Crises tend to drive action. I see the pandemic as a driver that will focus attention on the Department of Health and Human Services. The Biden team can make the point that to get the vaccines approved, to get the distribution done, to deal with the health crisis, you have to have someone at HHS. [This] should result in a faster confirmation process.”

Wolff and Schiliro described their proudest moments in the White House and biggest legislative accomplishments.

Wolff: “It was a privilege to work [in the White House], provide public service and support the American people. …The legislation that I’m most pleased with is when one of the last trade agreements that got through. I remember that passing with one vote in the House and feeling really good about knowing where the vote count was going to be.”

Schiliro: “It was a combination of things—trying to give the president a realistic, accurate assessment as we were developing strategies of what would work and what wouldn’t work, and having a team at the White House Office of Legislative Affairs that was just terrific. …If I had to pick a piece of legislation, it was the Affordable Care Act because it meant so much to the president, it was difficult to do and we had to navigate so many problems.”

Melody Barnes has a distinguished political career. She has worked in various roles on Capitol Hill, held senior positions with the 2008 Barack Obama presidential campaign and transition teams, and led the White House Domestic Policy Council from 2009-2012. Currently, she is the co-director for policy and public affairs at the University of Virginia’s Democracy Initiative. In this episode of Transition Lab, Barnes joined host David Marchick to discuss post-election transition planning, how new administrations plan and implement policy and why we need a smooth transfer of power today.

[tunein id=”t158772969″]

Read the highlights:

Barnes described how a transition team sets priorities after its candidate wins the presidential election.

Barnes: “Immediately, the transition begins to think about what the president is going to do on the day that he or she is inaugurated. For better for worse, America has become fixated on the first 100 days. …So [new administrations look at] executive orders, what’s been done by a prior administration [and] what might be overturned because of the law. [They also examine] what’s going to happen on Capitol Hill [and] the first pieces of legislation that a new administration wants to push. …It really is three-dimensional chess when a new administration walks in the door.”

Barnes discussed how the Obama administration decided which issues to focus on early in its first term.

Barnes: “People often questioned why this versus that. Why not do a big push on immigration coming out of the blocks? Why so big and comprehensive a health care bill right out of the blocks? Those were decisions that we made based both on substance and timing. We believed we had political capital that we could spend [and] that the nation had been focused on the issue of health care, [which] was also wrapped up in the issue of the economy. So we were thinking about all of those things—the politics, the substance and the signals that [we] were sending as [we made those] decisions.”

Barnes explained how transition teams process information after the election.

Barnes: “For the transition, it feels as though several trucks back up to the front door and unload reports, documents and lists of names. They just come spilling out. …And [transition teams are] trying to figure out how to … sift through what’s coming in that may or may not be useful. [In 2008], we created a process for tagging and accepting all of the reports and ideas that were coming through the door so that we would have access to them. And there was a very organized meeting process that was put in place so that we could talk to people. …What you don’t want to do is look at everyone that has supported the campaign … and all the expertise that sits on the other side of those doors and outside of government, and say, ‘Thank you so much. See you later, never.’”

Barnes offered advice on how to approach landing a job in a new administration.

Barnes: “[Share your information with] those who are doing personnel or those on the outside— whether it’s a caucus of members of Congress, or others that have a relationship with the campaign and the transition. …That’s another opportunity to put your information in a place where it will be received and processed. I also tell people that if you don’t get a call in the first few months, it doesn’t mean that you’ll never get a call. …Presidential personnel are getting thousands upon thousands upon thousands of resumes. So it will take a while, even if you are quite qualified, before they may turn to your information.”

Barnes discussed how new administrations work to implement big policy ideas.

Barnes: “One of the things that I learned working for Senator [Ted] Kennedy was that the best policy processes often begin with people putting lots of ideas on the table. Some of them are wacky, but possess the germ of something interesting and important. …It is the process of [refining] those ideas and engaging with the policy people, the legislative affairs people, the political people, the communications team and others to create something that has a snowball’s chance of getting over the finish line.”

Barnes explained why we need a smooth transition now more than ever.

Barnes: “Even as we go through this period where the current president will not agree that President-elect Biden is, in fact, President-elect Biden, the health of the nation [and] our national economy hang in the balance. [The Biden-Harris agency review] teams should be able to meet with folks at the Defense Department and the Department of Health and Human Services to do planning and work around [developing and distributing a coronavirus vaccine].”

Barnes discussed the challenges President-elect Biden might face working in a divided government.

Barnes: “It’s certainly easier when you don’t have divided government. People have often spoken about the fact that the president-elect has a long standing relationship with [Senate Majority Leader] Mitch McConnell and long-standing Hill relationships from his days in the White House and the Senate. I think those relationships will and could make a difference when there is agreement to move forward. …[But] the road will be challenging.”

Marchick jokingly asked Barnes whether she was upset about Kamala Harris’ ascension to the vice presidency, meaning that Barnes would no longer be considered one of the most senior women of color ever to serve in the White House.

Barnes: “I think about colleagues like [former White House Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy] Mona Sutphen and others. What an amazing group of women to have as peers. And I would venture to say that, to a person, we would all say that this is one of the proudest moments for each of us as women and women of color. …There is a history of political engagement and activism—from anti-lynching campaigns and suffrage to civil rights and so many other issues— that is a leitmotif that plays behind the careers [of government leaders who are women of color]. To see Kamala Harris standing there and accepting the congratulations of the crowd when the election had been called was just one of the proudest moments that I have ever had.”

By Alex Tippett and Carter Hirschhorn

With less than three weeks to go before the presidential election, job seekers for either a Trump second term or a Biden first term are dusting off their resumes and positioning themselves for potential appointments.

During our Transition Lab podcasts, a number of transition veterans detailed some of the least productive approaches for prospective job candidates. The following is a list of five lessons derived from these conversations. If you stick to them, you can reduce the possibility that your resume ends up in the recycling bin!

Avoid overwhelming the transition team

Prospective appointees sometimes think the best way to get a job is to have all their friends call the transition team or the White House personnel office with words of support. Don’t do it!

During a transition and in the early days of an administration, there can be anywhere from 150,000 to 300,000 applications for presidentially appointed positions. Unnecessarily adding to that workload will not make you any friends.

Liza Wright, who directed the Office of Presidential Personnel (PPO) under President George W. Bush, said, “To have all of these people start berating the office with phone calls and things like that…is not a good approach.” Jonathan McBride, who ran PPO under President Barack Obama, added, “If somebody can speak to the substance of what you can do or your acumen…that’s great. Twenty people saying that they like you does not help. And it becomes a judgment question after a while. If you approach this [job search] this way, when you’re acting on behalf of the president of the United States, are you going to show similar poor judgment?”

Job applicants should wait until after the election to send in their resume. Right now, you should secure letters of recommendation and start filling out the necessary clearance and disclosure forms. Carefully calibrate the way you demonstrate your support.

Stay out of the press

There is always a temptation for job seekers to audition in the media. This is a mistake. Press stories can create headaches for the transition teams and distract from the only campaign that matters—the presidential campaign.

Speaking with reporters Nancy Cook and Andrew Restuccia about their transition coverage, Transition Lab host David Marchick pointed out that “the lesson here for someone who wants to get a nomination is not to be in one of these stories because you might have a better chance of getting the job if you’re not in the story.”

Don’t be presumptuous

For every job in an administration, there are dozens if not hundreds of qualified applicants. Even if you have served before, there is no guarantee you will get the job you want. Ironically, accepting that reality might increase your chances of getting a job.

According to Michael Froman, who led the Obama 2008-2009 transition personnel effort, “People who came in and said, ‘I am the greatest expert in this area…where do I fill out my employment forms,’ usually did not get hired.” Froman said. “The more successful approach was to make clear that that you were low maintenance,…that there were a variety of positions that you could envisage yourself doing, that you were not insistent on necessarily being the top person in any agency, but you were willing to play whatever role the president-elect felt was appropriate for you.”

Don’t show up unprepared

While you should not assume you will get a specific job, you should have a sense of what types of jobs you are interested in.

“I always tell people to do your homework,” Wright said. “It’s so helpful if someone has gone to this kind of taking the steps to really research what positions in the government they’re interested in, what they believe they’re qualified for.”

Doing this legwork will show you are committed and thoughtful, and that might just win you some friends. Coming unprepared, however, might cost your resume a second look.

Don’t wait until your nomination hearing to be honest – disclose all information from the start

Potential nominees should be straight-forward with the transition team. Clay Johnson, who led George W. Bush’s personnel operation during the transition and also served as PPO director, told candidates, “I’m expecting total honesty from you…and if it turns out you have problems or conflicts, and you aren’t able to serve, you have to know that we’re going to drop you like a hundred-pound weight.”

What should you do pre-election? Support your preferred candidate and get ready. Part of this process involves familiarizing yourself with financial and ethics forms and preparing those materials so you are ready if the next administration would like you to serve. If you have questions about these forms, consider registering for our October 21 Ready to Serve webinar about financial disclosures, or viewing our previous two sessions on YouTube.

By Alex Tippett and Troy Cribb

During election seasons, the status of political appointees in the federal workforce come under increased scrutiny. Under all recent presidents, some political appointees have attempted to become civil servants — a process commonly called “burrowing in.”

Unlike political appointments, civil service positions do not terminate at the end of an administration. Conversion therefore allows political appointees to stay in government after the president who appointed them has left office.

These kinds of conversions inevitably create concerns. Supporters of an incoming president may be suspicious of individuals hired by the previous administration. More broadly, some fear conversions can violate the merit system principles that govern hiring in the federal civil service.

The hiring process for civil servants is designed to promote a professional, apolitical workforce and to prevent discrimination, political favoritism, nepotism or other prohibited practices. To ensure these rules are followed, the Office of Personnel Management reviews requests to move a political appointee into the civil service. This review is designed to prevent improper conversions while providing talented individuals with the opportunity to join the civil service.

How does OPM conduct oversight?

While OPM has reviewed conversions since the Carter administration, the process has changed over time. Currently, agencies must submit a request to OPM whenever they seek to hire a current political appointee or one who has served in a political position within the last five years. OPM conducts multi-level reviews of each application to make sure the conversion follows federal hiring guidelines.

If OPM believes a conversion violates federal hiring laws or regulations, it may reject the conversion. If OPM finds the agency’s conversion attempt violates the federal government’s prohibited personnel practices, it may refer the issue to the Office of Special Counsel for investigation.

On occasion, agencies have converted political appointees without going through the OPM review process. In those cases, OPM retroactively reviews the conversions and issues any necessary corrective actions, which can include re-advertising the position. Recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the firing of an appointee who had converted to a career position without an OPM review.

OPM’s procedure is not laid out in statute. Instead, existing laws and regulations broadly empower OPM to protect the civil service’s merit system. Individual OPM directors have interpreted this authority differently, with the rules tightening over the years. Previously, agencies only had to file a request for a smaller subset of political appointees and only for conversions taking place close to an election. OPM’s current regulations require that every conversion receive approval.

Congress also created specific reporting requirements for conversions. The Edward “Ted” Kaufman and Michael Leavitt Presidential Transitions Improvements Act of 2015 requires that OPM submit an annual report to Congress detailing the conversions. During the final year of a presidential term, these reports must be submitted quarterly.

How common is burrowing?

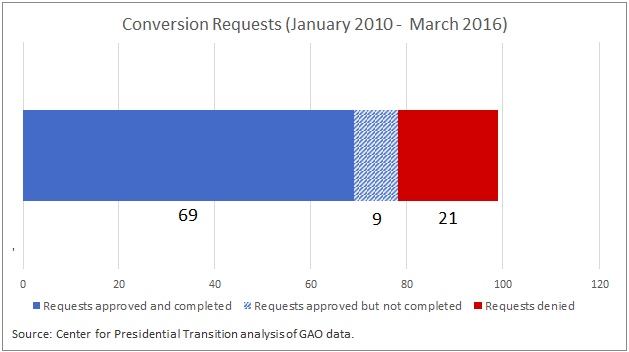

Investigations by the Government Accountability Office suggest that conversions are relatively rare. According to GAO’s most recent report in 2017, OPM received 99 conversion requests from January 2010 to March 2016. For context, during that period, the federal government hired about 100,000 people every year into full-time permanent positions.

Of those 99 requests, OPM approved 78, suggesting that most conversions followed proper procedure. The GAO found no reason to disagree with OPM’s assessments.

Of the 78 requests approved by OPM in the latest GAO report, only 69 were carried out. Occasionally, an applicant will decline to take the job after it is offered to them.

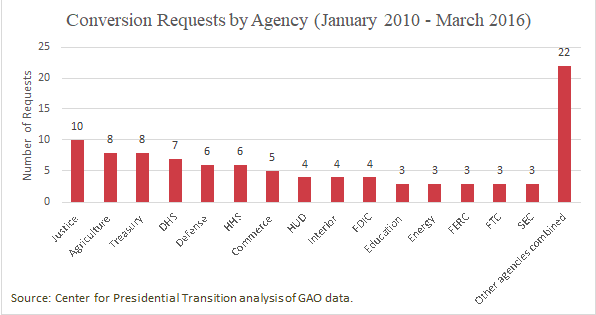

A relatively small number of agencies have accounted for a large portion of conversion requests. Between January 2010 and March 2016, approximately 10% of requests were initiated by the Justice Department. The top five agencies—Justice, Treasury, Defense, Agriculture and Homeland Security—accounted for nearly 40% of the conversion requests filed.

Some agencies have occasionally failed to request permission from OPM before carrying out conversions. There were seven instances of this cited by the GAO. When this occurs, OPM carries out a post-appointment review as soon as it becomes aware of the conversion.

Conversions themselves also tend to increase immediately before an election. While available data is incomplete, 47 conversions occurred in the final year of President George W. Bush’s presidency, up from 36 the previous year. At least 19 occurred in President Barrack Obama’s fourth year, up from 11 the previous year. GAO’s 2017 burrowing report does not include the final months of Obama’s administration or the entirety of the Trump administration.

Additional public data would be helpful

While the law requires OPM to report instances of burrowing to Congress, neither the agency nor the House Committee on Oversight and Reform or the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs have made the information public. Doing so is in the public interest and could help guard against potential abuses.

Michael Froman has had an extraordinary career. After serving in the Department of the Treasury under President Clinton, he became the head of personnel for the 2008 Obama-Biden transition team and later served as a White House deputy national security advisor and as the U.S. Trade Representative. In this episode of Transition Lab, host David Marchick asks Froman for an inside look at the world of vetting, selecting and appointing key presidential personnel. They discuss how Froman got involved in transition planning, the lessons his experience holds for future administrations and President Obama’s personnel strategy.

[tunein id=”t157772631″]

Read the highlights:

Marchick asked Froman how he got involved in the 2008 Obama-Biden transition.

Froman: “I had known President Obama from [Harvard] Law School. …And when he became senator, a group of us whom he had known either from law school or other places had helped … hire some of his initial staff. …When he decided to run for president, I offered to help him with the transition, in part because I wasn’t planning on going into government and thought that I could make a contribution by helping him with the personnel process.”

Marchick asked how potential nominees for President Obama’s Cabinet were selected.

Froman: “We’d look at the national security team, the economic team, the domestic policy team, the environment team and come up with lists of names of people who could fill potentially multiple positions. The approach was more to look at teams rather than individual positions. It wasn’t so much having five candidates for one job, but more of having 15 candidates for a handful of jobs. …It was more going out and looking for as many qualified, diverse candidates as possible so that the president would have maximum opportunity to … [put] together the Cabinet that he wanted.”

Marchick asked which personnel decisions took priority.

Froman: “His first decision was not a Cabinet position. It was the position of White House chief of staff and he chose Rahm Emanuel, which also then helped further the process because Rahm was very focused on both the Cabinet and the White House staff. …Because of the global financial crisis, there was a particular momentum for getting decisions around the economic team.”

Marchick asked whether the campaign staff jockeyed for jobs in the administration after the 2008 election.

Froman: “There certainly was an element of that, but people were actually engaged in pretty good behavior. …People [on the] campaign … of course had hoped to get into the administration, but there weren’t a lot of sharp elbows … [President Obama] had not been in Washington for years and years, and he didn’t have a list of a thousand people that he needed jobs for. …He was really quite open to meeting whoever was the the best candidate for the job.”

Marchick asked how successful candidates approached the vetting process for a position in the Obama administration.

Froman: “People who came in and said, ‘I am the greatest expert in this area, I have served the three of the last Democratic administrations and I am clearly the most qualified person for this position. Where do I fill out my employment forms?’ didn’t tend to [do] very well. …The more successful approach was to make clear that you were low maintenance; that you wanted to serve; that there were a variety of positions that you could envisage yourself doing; that you were not insistent on necessarily being the top person in any agency; [and] that you were willing to play whatever role the president-elect felt was appropriate.”

Marchick asked what lessons future administrations should take from the slower rate at which President Obama filled Senate-confirmed positions after his first year in office.

Froman: “One of the lessons of that is that it’s better to have somebody who is doing personnel during the transition into at least the first year of the administration—maybe into the first two years of the administration. Having that continuity would have been better in retrospect.”

Marchick asked why President Obama wanted to build a diverse Cabinet.

Froman: “The president had made clear he wanted an administration that looked like America, and we were committed to having a diverse Cabinet and sub-Cabinet … So one of our areas of focus was ensuring that the slates [of potential nominees] were as diverse as possible—whether it was racial diversity, ethnic diversity, gender diversity, among other attributes.”

Marchick asked Froman to discuss the advice he would offer presidential transition personnel planners.

Froman: “When you’re picking a team of Cabinet and sub-Cabinet officials, one should be thinking about who [we are] putting in the pipeline who could succeed the Cabinet, and how do we make sure that they get the support and the training … to fill out their attributes so that they could step up be Cabinet officers as well. The one thing we don’t do terribly well in the federal government compared to some of other organizations, including in the private sector, is [think] about succession planning [and] how to prepare people to step up into the next position.

Editorial credit: Katherine Welles / Shutterstock.com

By Bruce Andrews

This post is part of the Partnership’s Ready to Serve series. Ready to Serve is a centralized resource for people who aspire to serve in a presidential administration as a political appointee.

The opportunity to serve in a presidentially-appointed position in the federal government is a unique privilege and honor. For some positions, this means nominees must traverse the difficult Senate confirmation process before they can take office.

The confirmation process can be one of the biggest challenges a nominee will face in their lifetime. The process puts the fate of a highly accomplished individual in the hands of a Senate committee and a small group of staff, followed by the full Senate for a vote. Rarely do nominees depend so heavily on the judgment of others.

I had the opportunity to work on several sides of the process— first overseeing nominations for the Senate Commerce Committee as the general counsel, then helping nominees navigate the process as chief of staff of the Commerce Department, and finally working on my own nomination to be deputy secretary of Commerce. Here’s some advice for navigating the process.

Tip 1: Be honest

Nominees rarely know how intrusive the process will be and how deeply the background check and the committee will get to know them. In my experience, it is most important to be fully transparent and honest. It is always better to disclose everything, even embarrassing information, rather than be seen as untruthful or misleading.

Tip 2: Trust your team

Remember that confirmation is a team sport! Nominees need champions to build support and to work with potential critics.

The good news is that nominees have a confirmation team to help them. Trust the team. They are experts and their job is to help get the nominee confirmed. They are selected for their understanding of the process and have many resources to draw from.

Tip 3: Think about relationships

Prior to confirmation, nominees should catalogue their relationships and identify third party validators.

When thinking about relationships, some key questions to ask include:

- Which senators do you know?

- Do you have friends who know key senators?

- Do you have people who can vouch for the nominee?

- Can your home state senators help?

When I went through confirmation, I thought I would be fine with Democrats, but wanted to strengthen my support among Republicans. I was fortunate to have a group of well-connected Republicans who served as my “Shadow Confirmation Team.” They enthusiastically helped me by reaching out to key Republican senators, committee and leadership staff. Not everyone is as fortunate to have that kind of assistance, but all nominees will benefit from examining their own networks for potential help.

A crucial step in the process involves meetings with members of the Senate committee that has jurisdiction over the position you are seeking. These meetings may be with senators or their senior staff. They are the best way for nominees to introduce themselves, learn about the important issues from each committee member and earn their support.

Tip 4: Remember the hearing is part interview and part political theater

Next, the confirmation hearing will be scheduled. The hearing is not just an opportunity for the nominee to answer questions, but also for senators to impress on the nominee what they see as most important and show their constituents they are fighting for them. If senators want to spend three of their allotted five minutes talking about their positions, that is great. It is less time for the nominee to have to answer questions.

During my hearing, one senator asked me to come meet the fishermen in her state. I first suggested they meet with the regional official as instructed by my confirmation team. She then asked a second time, and I repeated the crafted response. On the third time she pressed me, I finally agreed to visit her state. (After the hearing, my eight-year-old daughter asked why I didn’t just agree when she asked in the first place.) After I was confirmed, my team reached out to her office to schedule a trip to meet with the fishermen, but her office never followed up.

Tip 5: Only answer the question that is asked

Many nominees want to show how smart they are. The most important thing is to listen to what the committee members are asking, and do not go beyond the question. Many nominees get in trouble by straying off topic.

I will never forget one hearing I staffed when a nominee violated this rule and tried to answer questions that were not asked to show the breadth of his knowledge. His responses raised concerns from several senators and led to an entirely new set of tougher questions. No one should want to be that nominee.

The confirmation process is not always easy, but it is a time-honored part of our democracy. Serving your country is an incredibly rewarding experience, but it is important to respect the crucial role of the Senate in that process, and preparing wisely will increase the chance for a successful confirmation.

Bruce Andrews is managing partner at SoftBank Group and a former deputy secretary for the U.S. Department of Commerce. He also served as general counsel to the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee.

By Thomas Kean and Lee Hamilton

Presidential transitions are a time of great vulnerability for our nation, with a significant turnover in national security personnel occurring when the nation may be facing a foreign policy crisis or an adversary willing to cause significant trouble. Many of the laws and norms that presidential transitions follow today were put in place based on lessons learned in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

The independent, bipartisan 9/11 Commission, which we headed, examined the transition of power in 2001 from Bill Clinton to George W. Bush. We found, among other things, that the Bush administration, like others before it, did not have its full national security team on the job until at least six months after it took office.

Since a catastrophic attack can occur with little or no notice as we experienced on 9/11, we concluded that the government must seek to minimize disruption of national security policymaking during the change of administrations. In exploring this issue, our report made a series of recommendations to protect the nation from national security threats during a presidential transition.

Our proposals were adopted by Congress largely through the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004. The post 9/11 provisions have been integrated into the process for all transitions since and include:

- The designation of a single federal agency responsible for all security clearances. This task was originally given to the National Background Investigations Bureau at the Office of Personnel Management, and in April 2019 was moved to the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency.

- A requirement that the outgoing administration provide the incoming administration with a “detailed classified, compartmented summary” of national security threats, major military and covert operations, and pending decisions on possible uses of military force.

- A recommendation that the president-elect submit the names of candidates for high-level national security positions (through the level of undersecretaries of Cabinet departments) to the FBI as soon as possible after the general election, and that the responsible agencies conduct the background investigations necessary for the appropriate security clearances.

- A nonbinding sense of the Senate resolution calling on the president-elect to submit national security nominations to the Senate prior to the inauguration, and that all of those received prior to that date will receive a vote by the full Senate within 30 days of submission.

- The ability of each major party candidate to submit requests for security clearances for prospective transition team members who may need access to classified information to carry out their responsibilities. The law requires that necessary background investigations be completed by the day after the conclusion of the general election.

To be truly effective and help protect our nation from national security threats during and soon after a presidential transition, our outgoing and incoming leaders must be cooperative, take these requirements and best practices seriously, and act in the best interests of the nation.

Thomas Kean, a former Republican governor of New Jersey, and Lee Hamilton, a former Democratic congressman from Indiana, served as chairman and vice chairman, respectively, of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States.

By Christina Condreay and Alex Tippett

The winner of this November’s presidential election will face daunting challenges—a devastating pandemic, a major economic crisis, civil unrest stemming from racial inequality and a long list of pressing domestic and national security issues. These are momentous times that accentuate the need for presidential transition planning, whether it’s a first term for Democratic candidate Joseph Biden or a second term for President Donald Trump.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout will impact presidential transition planning in four key areas:

- Planning a budget and policy agenda.

- Making priority appointments to top federal jobs.

- Developing executive actions.

- Creating the White House organizational structure.

Additionally, a first-term Biden administration will have to consider a fifth area–the preparation for “landing teams” that are deployed by incoming presidential administrations to review agencies operations and policies.

The president’s budget is an important opportunity to signal the priorities of an administration, shape the congressional debate and shore up alliances.

In 2021, the president’s budget will come on the heels of congressional approval of several trillion dollars in stimulus spending in 2020 and will involve weighing trade-offs between the administration’s long-term policy agenda and the requirements dictated by the current crises. This will necessitate a high-stakes appraisal—the funding choices in this budget could shape the economic and political landscape for the next four years. Due to these challenges, work on the budget should begin early and be given greater attention and resources than in previous election cycles.

Chris Lu, the executive director of the President Barack Obama’s 2008-2009 transition, said the severe financial crisis occurring when Obama took office pushed many policy concerns “to the backburner.” Transition planners should develop the budget to highlight major policy goals for the year ahead even if the immediate crisis remains the top priority.

Presidents are responsible for appointing about 4,000 officials throughout the federal government. A new president must fill these positions from scratch while second-term presidents often face significant staff turnover. According to previous research by the Partnership for Public Service, the first year of a second term coincides with an average turnover rate of more than 40% for senior leadership positions. Both before and after the Nov. 3 election, it is critical for transition planners to focus on public health and economic policy appointees who will be responsible for overseeing the response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the sagging economy.

The specific priority positions will depend on how a new administration structures its response, while a second-term administration may take the opportunity to reshape its efforts. A Cabinet-led response will require the administration to prioritize agency leadership positions while a response driven by the White House will call for a different staffing structure. Transition planners should develop a clear picture of what the post-election COVID-19 response will look like and identify key personnel for this effort.

The pandemic also has created several second-order threats such as increased cybersecurity risks with a remote workforce as well as greater global instability. The next administration should recognize that successfully navigating the current crises will require filling positions without traditional “pandemic-response” roles in agencies throughout the government.

The pandemic also will create operational challenges for presidential appointees. Procedures will have to be developed for previously routine issues, ranging from how to conduct safe and secure briefings with new appointees to the best way to work with a potentially remote Senate. The challenger’s transition team will need to closely coordinate with the General Service Administration (GSA), which provides the transition with office space, IT equipment and other support.

According to Mary Gibert, the federal transition coordinator at GSA, the groundwork for a virtual transition, however, has already been laid. In the last transition, much of the work was already conducted virtually, with many of personnel choosing to work on GSA-provided devices rather than come into the office. “COVID has not impacted our transition planning,” Gibert says. “We haven’t missed a beat. We’ve kept up with all our statutory requirements.”

Those involved in overseeing a second Trump term will have to ensure the Office of Presidential Personnel can ramp up its efforts to meet an expected turnover of political appointees on top of a high level of current vacancies, and determine where it can improve operations and procedures to better deal with the challenges resulting from the pandemic.

Prioritizing key executive actions will advance policy goals

Executive

actions are one tool presidents can use to enact significant change–and do so

quickly. Effectively using executive orders for achieving policy goals may

be more challenging in 2021 because so much attention must be devoted to

dealing with the immediate crises. Transition planners for both first- and

fifth-year administrations should take time to develop executive orders and

anticipate potential operational and legal challenges well before Jan. 20.

First-year administrations face a two-pronged challenge. They must advance the new president’s agenda while evaluating previous executive actions and rules they want to change. This can be a huge undertaking even under normal conditions. Resource constraints created by the pandemic will make it difficult for a new administration to accomplish all its goals. An incoming administration should concentrate on the most critical subset of issues. Doing so will prevent it from spreading itself too thin and increase its chances of success. Historically, there has been a decline in the number of executive orders issued by a president during the fifth year in office compared with the first term. In interviews with the Partnership for Public Service, former senior White House officials suggested the focus on re-election often limits formal planning for a president’s fifth year. If an administration is facing both a crisis and a re-election campaign, as is the case today, developing fifth-year executive orders may well fall to the bottom of the agenda. Investing time and resources in planning an executive agenda now, however, may allow the president to start the fifth year more effectively and set a productive tone for the rest of their presidency.

The White House structure must be equipped to respond to the current and future crises

All presidents seek a White House

organizational structure that will lead to a smooth functioning operation and enable

them to achieve their key policy priorities. New administrations must create this

structure from scratch while a second-term administration has the opportunity

to reexamine its White House design and improve areas of weakness. Any such

redesign, however, will need to be attuned to the demands of the current crisis.

Different presidents have relied on a variety of organizational structures to address crises. During Harry Truman’s presidency, Congress created the National Security Council in 1947 to help the president coordinate national security policy. In 1993, President Bill Clinton created the National Economic Council by executive order to help coordinate the economic policy-making process and provide economic policy advice.

These entities centralized decision-making and the flow of information. Other presidents have relied on temporary arrangements such as President Obama’s appointment of an Ebola czar in 2014 to coordinate what was then the world’s biggest health threat. This type of temporary structure can be valuable but cannot provide the same institutional knowledge offered by a more permanent organization. Both first- and fifth-year administrations should use the transition period as an opportunity to evaluate the current pandemic response structure and determine if changes are needed. The next administration also should assess how to operate in a partial virtual work environment. A new administration should seek expert guidance and develop contingency plans while the current administration should identify problem areas that need to be resolved. Identifying and resolving these issues long before Inauguration Day will ensure a smooth start for a new administration or lead to improved conditions for a second term. Lessons could be learned from the agencies across government who are currently operating partially or totally virtually. Despite working virtually, agencies like the IRS and FEMA have managed to fulfill their normal mission requirements in addition to the new demands created by COVID-19. A new administration will have to demonstrate a similar level of agility.

A new administration must understand how agencies operate

A

new administration must have a thorough understanding of every federal agency’s

capabilities and responsibilities. To do this, presidential transition teams traditionally

create landing teams that enter agencies following the election and gather relevant

information. The roles of various agencies can change rapidly during a crisis. The

transition landing teams must flag challenges related to the pandemic so that

those issues can be evaluated and resolved.

Landing teams should also map the statutory landscape for each agency. Do agencies have emergency powers they are not taking advantage of? Are agencies exceeding the legal limits of their authority? An incoming administration must be aware of all these issues to mount an effective COVID-19 response. In addition, federal agencies must coordinate with one another, the private sector, state and municipal governments, and international partners during a crisis such as a pandemic. Landing teams should document these relationships so an incoming administration can take immediate control and identify potential pain points that need to be resolved.

Conclusion

Whether it’s a second Trump term or a first term for Biden, our

government must be prepared to tackle the pandemic and the nation’s economic problems

in addition to the challenges associated with any presidential transition. This

will require thorough transition planning that accounts for the uniqueness of

the current crises.