1 Constitution of the United States, Article. 2, Section. 2, cl.2

2 Hill, Fiona. “Public Service and the Federal Government.” Brookings Institution, November 5, 2020. Retrieved from https://brook.gs/373ZZEe

3 “Why Is It So Hard for Joe Biden to Hire People?” The Economist, May 27, 2021. Retrieved from https://econ.st/3yapQGj

4 Most of the appointee data used in this report is based on appointee tracker databases from the Partnership for Public Service. Researchers at the Partnership follow presidential and congressional actions on approximately 800 top executive branch positions, a portion of the roughly 1,200 positions that require Senate confirmation. The tracker includes all full-time civilian positions in the executive branch that require Senate confirmation except for judges, marshals and U.S. attorneys. Military appointments and part-time positions requiring Senate confirmation are not included.

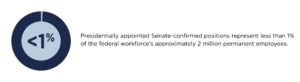

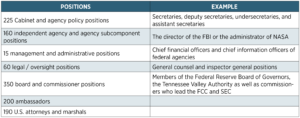

5 Plumer, Brad, “Does the Senate Really Need to Confirm 1,200 Executive Branch Jobs?” The Washington Post, April 28, 2019. Retrieved from https://wapo.st/3i4lDi2

6 David Lewis’s analysis of U.S. Congress, Policy and Supporting Positions, various years; and Partnership for Public Service analysis of U.S. Congress, Policy and Supporting Positions, various years.

7 The creation of additional layers of political and career management positions to our government’s leadership structure has also “thickened” the federal workforce. In 1961, John F. Kennedy inherited 451 positions; in 2017, Donald Trump inherited 3,265. From 1961 to 2016, the number of layers grew by 750%, and the number of leaders per layer grew by 625%. Light, Paul, “The True Size of Government.” The Volcker Alliance, October 2, 2017. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3l5M3BM

8 Lewis, David E., “The Contemporary Presidency: The Personnel Process in the Modern Presidency.” Presidential Studies Quarterly, 42 (3), 2012, pp. 577–596. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2012.03993.x

9 “Between 1960 and 2008, the number of appointees in the Bureau of the Budget/Office of Management and Budget (budgets, regulatory review) increased from 11 to 37 appointees, while the number of appointees in the Civil Service Commission/Office of Personnel Management increased from 3 to 30.” Lewis, David E., “The Contemporary Presidency: The Personnel Process in the Modern Presidency.” Presidential Studies Quarterly, 42 (3), 2012, pp. 577–596. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2012.03993.x

10 Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011 (2012). Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3zEbVJ6

11 David Lewis’s analysis of U.S. Congress, Policy and Supporting Positions, various years; and Partnership for Public Service analysis of U.S. Congress, Policy and Supporting Positions, various years.

12 “Senate Confirmation Process Slows to a Crawl.” Center for Presidential Transition, January 21, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3x7BkZW

13 Ibid.

14 Hitlin, Paul. “Senate Taking Longer To Confirm Biden’s Cabinet Than for Most Recent Presidents.” Center for Presidential Transition, Partnership for Public Service, 4 Feb. 2021, https://bit.ly/3f4nX6O

15 Beth, Richard S, et al, “Cloture Attempts on Nominations: Data and Historical Development Through November 20, 2013.” Congressional Research Service, September 28 2018. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3y8xi55

16 “Senate Confirmation Process Slows to a Crawl.” Center for Presidential Transition, January 21, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2TCpDNc

17 Carey, Maeve P., “Presidential Appointments, the Senate’s Confirmation Process, and Changes Made in the 112th Congress.” Congressional Research Service, October 9, 2012. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3eYinm7

18 “Senate Traditionally Confirms First Cabinet Secretaries Within Days of Inauguration.” Center for Presidential Transition, December 4, 2020. https://bit.ly/2UTrJJg

19 Kinane, Christina M., “Control without Confirmation: The Politics of Vacancies in Presidential Appointments.” American Political Science Review, 115 (2), 2021, pp. 599–614. doi:10.1017/s000305542000115x

20 Partnership for Public Service analysis of U.S. Congress, Policy and Supporting Positions, 2021.

21 Lewis, David E., and Mark D. Richardson, “The Very Best People: President Trump and the Management of Executive Personnel.” Presidential Studies Quarterly, 51 (1), 2021, pp. 51–70. doi:10.1111/psq.12697

22 “The Replacements: Why and How ‘Acting’ Officials Are Making Senate Confirmation Obsolete.” Partnership for Public Service, September 23, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3i7HOE4

23 O’Connell, Anne Joseph, “Actings.” Columbia Law Review, 120 (3), 2020, pp. 613–728. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/26910475

24 As of October 26 of 2020

25 It is estimated that President Trump had 1,583 political vacancies at the end of his term, including jobs for Senate-confirmed roles and other political appointments, such as statutorily created appointments not requiring Senate confirmation. Ogrysko, Nicole. “At Some Agencies, Acting Leadership Often Outlasted Permanent Appointees Over Last 4 Years.” Federal News Network, January 28, 2021. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3ycAPPF

26 Ibid.

27 Thrush, Glenn, et al, “How the A.T.F., Key to Biden’s Gun Plan, Became an N.R.A. ‘Whipping Boy’.” The New York Times, June 18, 2021. Retrieved from nyti.ms/3edFGs8

28 Bergengruen, Vera, and Brian Bennett, “Trump Ramps Up Coronavirus Response But Key Vacancies Remain.” Time Magazine, February 28, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2WlNfGN

29 Such as Assistant Administrator for Global Health; Associate Administrator for Relief, Response and Resilience; Assistant Administrator for Asia; and Associate Administrator for Strategy and Operations.

30 Similarly, the Department of State had no nominee for Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs, along with more than two dozen ambassadorships with no nominees.

31 This number reflects 2021 dollars based on an original estimate conducted in 2001 and assumes that the average annual salary for the reduced political appointee positions would be on average $164,200. Ogrysko, Nicole, “Why Political Appointees Are Getting a Pay Raise and Most Career Feds, for Now, Aren’t.” Federal News Network, January 8, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/371jTzR

32 Lewis, David, et al, “Strengthening Administrative Leadership, Fixing the Appointment Process.” Memo to National Leaders, National Academy of Public Administration, 2012. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3f3Z0It

33 Ibid.

34 “Reforming the Role of Chief Financial Officers.” Center for Presidential Transition, January 5, 2021. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3y846uJ

35 Like early versions of the Federal IT Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA)

36 Boyd, Aaron, “CIO Roundup: Here Are the Government’s Top Tech Chiefs So Far.” Nextgov.com, April 14, 2021. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2TEGvD9

37 Where’s the CIO? The role, responsibility and challenge for federal chief information officers in IT investment oversight and information management.” 108th Congress, 2004. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3yaiAKP

38 Carey, Maeve P., “Presidential Appointments, the Senate’s Confirmation Process, and Changes Made in the 112th Congress.” Congressional Research Service, October 9, 2012. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3f2g6Xr

39 Marchsteiner, Kathleen, “Presidential Appointments to Full-Time Positions on Regulatory and Other Collegial Boards and Commissions, 115th Congress.” Congressional Research Service, April 20, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3BOEHbW

40 Lewis, David E., and Mark D. Richardson, “The Very Best People: President Trump and the Management of Executive Personnel.” Presidential Studies Quarterly, 51 (1), 2021, pp. 51–70. doi:10.1111/psq.12697)

41 Hudak, John, “Appointments, Vacancies and Government IT: Reforming Personnel Data Systems.” Brookings, July 28, 2016. Retrieved from https://brook.gs/3iQPhXf

42 Congressional Research Service, Appointment and Confirmation of Executive Branch Leadership: An Overview (2015)

43 In recent administrations, politically appointed officials stay an average of 2.5 years. Several issues encourage short service, but two are noteworthy, the lack of express commitment to serving longer and inadequate training for the position.” Anne Joseph O’Connell, Memo #4: Decreasing Agency Vacancies, Memo to National Leaders.

44 According to a 1994 report from GAO, term-limited appointees generally serve longer in their positions than their indefinite-tenure counterparts. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Political Appointees: Turnover Rates in Executive Schedule Positions Requiring Senate Confirmation, April 21, 1994. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3x2gxag

45 Examples include the Director of the Bureau of the Census and members of the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority’s Board of Directors.

46 Due to some of the criteria mentioned above (e.g., require rare and difficult to source expertise).

47 Lewis, David E., “The Contemporary Presidency: The Personnel Process in the Modern Presidency.” Presidential Studies Quarterly, 42 (3), 2012, pp. 577–596. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2012.03993.x

48 Cohen, David M., “Amateur Government: When Political Appointees Manage the Federal Bureaucracy.” Brookings, July 28, 2016. Retrieved from https://brook.gs/3zH2iJH

49 Marchsteiner, Kathleen, “Presidential Appointments to Full-Time Positions on Regulatory and Other Collegial Boards and Commissions, 115th Congress.” Congressional Research Service, April 20, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2VfIhe6

50 Ibid.

51 Count based on the United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions (Plum Book) 2016.

52 Light, Paul C., “Federal Bloat Is at a 60-Year High.” Brookings Institution, November 3. 2020. https://brook.gs/2ULI0A3

53 Ibid.

54 Lewis, David E., and Mark D. Richardson, “The Very Best People: President Trump and the Management of Executive Personnel.” Presidential Studies Quarterly, 51 (1), 2021, pp. 51–70. doi:10.1111/psq.12697