Personal Impact

During the wait for confirmation, nominees not only risk their job prospects, but also their reputations and professional status. These potential burdens worsen the longer it takes to get confirmed. “You want to say it’s not personal, but it feels awfully personal because it’s your reputation on the line,” said Chris Lu, a former representative to the United Nations for Management and Reform. “Nowadays, it’s not uncommon for most nominees to be raked through the coals, and the scrutiny is often unfair and completely unrelated to the nominee’s qualifications. It’s emotionally draining.”

The uncertainty of a final confirmation falls particularly hard on the children of nominees, who may struggle to thrive amidst the uncertainty. Jen Gavito, former nominee for U.S ambassador to Libya, illustrates the toll that an extended confirmation process takes on an entire family. After undergoing a lengthy pre-nomination process, her nomination waited in the Senate for nearly a year before she asked for her nomination to be withdrawn. “We [had] been existing in a transient status for three years on one bureaucratic salary,” said Gavito. “After my hearing in June, my colleague from the other side of the aisle informed me that [a senator] was going to put a hold on my nomination. After getting off the phone, my son asked, sobbing, what I had done wrong to cause that. [My kids] had thought they were leaving. You see it in them. The younger one had not invested in any relationships because he thought we were moving on soon.” Ultimately, Gavito said, she withdrew because “I could no longer prioritize this at the expense of my family.”

Professional Impact

Delays impact the careers of nominees before they are confirmed. Nominees lucky enough to continue holding jobs during the wait are hamstrung as “lame ducks” in their existing roles. Whether in the public or private sector, once a nomination is officially announced, a nominee’s colleagues know that they’re not long for the role, which many nominees cite as a challenge. Their looming exit may prevent them from taking on new work or effectively completing current tasks; too often, it can damage relationships with their colleagues, forcing them to end roles on a sour note.

Once I was named officially for the nomination, I became a lame duck to my colleagues since they would ask, “Aren’t you leaving? Aren’t you going to your new post?” This…eroded my effectiveness.A U.S. ambassador

A key feature of the confirmation process is the freezing effect that it has on those in the midst of it: nominees cannot take on new roles or make major life changes while they wait, or they risk having to revisit and update their vetting paperwork – to reflect changing financial and background information.

Withdrawing from the process can also damage professional relationships and reputations. Nominees who have been waiting a long time and suffering the consequences can find themselves trapped in a catch-22. “You can drop out and apply for other positions,” said Pam Tremont, U.S. ambassador to Zimbabwe, “but doing that after two years – forcing the agency to start from scratch – would likely have burnt bridges.”

Financial Impact

For nominees who find themselves out of work and unable to take on new jobs while waiting for confirmation, delays create financial difficulties that fall particularly hard on long-time civil servants without large reserves of wealth.

Nominees who are coming from other government jobs may be able to keep serving until their confirmation, but some end up like Joyce Connery, who had been an agency detailee to the National Security Council when she was nominated to the Nuclear Defense Facilities Safety Board. Once nominated, she helped find a successor for her NSC role but then couldn’t be sent back to her agency because of a potential conflict of interest. “I negotiated a role to sit as a detailee somewhere else,” said Connery, “because I didn’t know how long I would wait.” In the end, she waited 114 days.

An official up for renomination to the Postal Regulatory Commission faced an even more frustrating situation. Despite being renominated in a timely manner, the official’s hold over year expired while waiting for reconfirmation and they retired under involuntary separation status for just under a year until they were reconfirmed and rejoined the Commission. “It was very frustrating to find myself retired when I wasn’t expecting it,” said the official. “I had lost my income. That in itself is a hardship. And not knowing what was going to happen – when do I start looking for a job?”

Former nominees who managed to wait out a gap in employment leaned on partners or prior income to do so, though these individuals tended to come from the private sector and jobs more lucrative than those in government. “Being in government, it’s much harder to go paycheck to paycheck, role to role,” said Jim Schwab, former director of the Office of Management Strategy and Solutions at the State Department. “The wealthier you are, the more options you have. If you’re wealthy, you can wait for a year, work on your ranch, sit on boards, or do advisory work, then say, ‘Oh hey, my hearing’s next week… time to go back to D.C.’” A nominee without these resources may not be able to afford waiting for a confirmation that might never come. Excessive delays hinder the government’s ability to draw the best talent for appointed positions from across the economic spectrum.

The confirmation process itself also incurs expenses. “Nobody’s paying for your travel expenses or reimbursing you for lost compensation. Like me, many nominees have to stop working to avoid potential conflicts arising from their nominations,” said Michael Desmond, a former IRS chief counsel who lived in California at the time of his nomination. Nominees like Chris Koos, who was based in Illinois, can run up major bills. To keep his nomination moving, Koos needed to make multiple cross-country trips to Washington, D.C., during the 630 days that his nomination to the Amtrak board of directors was pending, all of which he paid for out of pocket.

Nobody’s paying for your travel expenses or reimbursing you for lost compensation. That often has the effect of limiting the nominee pool to a select group of independently wealthy people who can afford to travel, relocate to Washington and forego work indefinitely, ultimately taking office at a compensation level that is often a fraction of what they were previously earning. This is why it is often only millionaires and billionaires who are able to take these positions: because no one else can afford the process.Michael Desmond, former IRS chief counsel

Nominees may need to pay for professional support to get them through the process. From financial advisors to lawyers, administrative assistants and even public relations consultants, professionals can help nominees but come with a hefty price tag. Steve Preston, the former head of the Small Business Administration and later the Department of Housing and Urban Development, said that it was costly when he was up for his nomination to HUD in 2008, “It was over $17,000 simply to update my previous filing. It’s very expensive and keeps a lot of people away.”

Family Impact

Delays in the confirmation process impact not just the individual under consideration, but also their families. Partners and children of nominees may find themselves in limbo about whether and when they may need to relocate. This uncertainty becomes a particularly challenging hurdle for nominees with children, who need to plan around school schedules.

Multiple ambassadorial nominees shared stories of needing to leave their children behind to complete school while they went on to new jobs overseas. Former nominee to be U.S. ambassador to Libya Jen Gavito’s son was an eighth grader when she was first nominated. By the time of her withdrawal, he was a high school junior.

Other members of the Gavito family felt the impact of the confirmation delay, too. “We have been existing in a transient status for three years on one bureaucratic salary,” Gavito said. “My son plays travel soccer [that we had to sign on for in the spring], which is about $3,500 that we would have forfeited if confirmed. We had to re-sign our lease in May and my hearing was in June. Had I been confirmed, we would have paid a significant fee to break that.” The individual they were renting the home from then returned, forcing their family of four to move into a 1,100 square foot apartment in Washington, D.C., where they were still living at the time of our interview. The stress weighed on all of them: “My husband woke up on multiple nights wondering what he had done, in his words, ‘to derail my career,’” Gavito said.

The process took a significant toll on the health of my family…the impact of this on people is not understood. I can go on and on about the impact on my family, financial security, college savings, quality of life.Jen Gavito, former nominee for U.S. ambassador to Libya

I had to leave my assignment in Sweden while my son was completing his IB program and we weren’t sure if there would be the right course offerings in Zimbabwe. We paid…for boarding school but it was expensive and being across the ocean for the last two years of my son’s high school was extremely difficult.Pam Tremont, U.S. ambassador to Zimbabwe

Another nominee from the West Coast spoke about the layers of stress with the uncertainty of the confirmation process. Because they didn’t know the timing of confirmation, should it occur, he and his wife struggled to figure out when she needed to start applying to jobs in Washington, D.C., as well as when to move their two school-age children, including one with a disability. Ultimately, they chose to move the family to Washington the summer after the nomination was announced so that the children would be able to start school in the new year, but the nominee himself then waited in limbo until the following April when he was finally confirmed. Unable to take on new roles or opportunities, he spent this time learning what he could from current and former officials and stakeholders, but the strain and expense of moving cross-country and the time out of work had a real impact on his family.

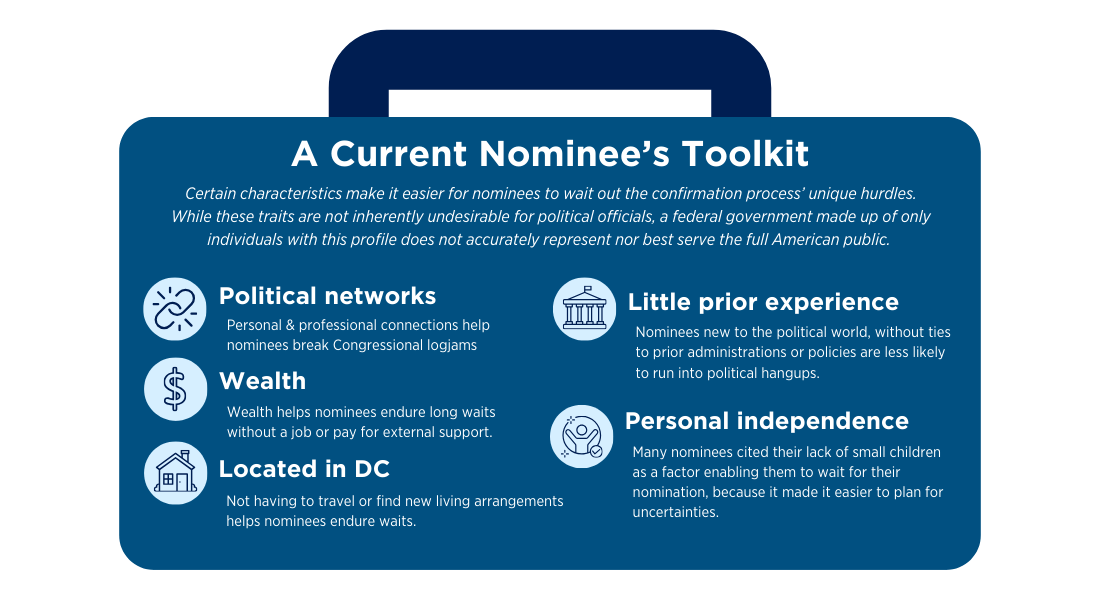

Notably, of the nominees we interviewed who were ultimately confirmed, most did not have young children while attempting the confirmation process and many cited this as a factor enabling them to wait it out. Self-selection of parents out of consideration for roles that require Senate confirmation eliminates a major proportion of mid-career talent that have much to offer as potential appointees.