Executive Summary

Photo credit: White House/Joyce N. Boghosian

The transfer of presidential power is always a difficult process, but the 2020–21 transition from Donald Trump to Joe Biden was particularly arduous due to a combination of crises facing the country. This included the COVID-19 pandemic, an economic downturn, a nationwide reckoning on race, the outgoing president’s unwillingness to accept the election results and the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

| The United States ultimately upheld its long tradition of the peaceful transfer of power on Jan. 20, 2021, and Biden began governing immediately with a substantial foundation of planning and personnel in place. This was in large measure due to months of preparation taken well in advance of the election, including contingency planning and the tireless efforts of many career agency executives, dedicated public servants within the Trump White House, and a Biden-Harris transition team that succeeded in building an impressive, well-resourced and organized transition

Nonetheless, the events of 2020–21 revealed longstanding areas of fragility in the presidential transition process. Trump’s refusal to concede the election led to a delay in ascertainment—the formal decision that initiates the government’s post-election financial and substantive support for the winning candidate. In addition to delaying funding and access to federal agencies, some members of the Trump administration were not fully cooperative with the incoming Biden team, further complicating matters. In previous transitions, some practices have been determined by law. Other major elements have been governed by norms and traditions. Sitting administrations helped a new administration prepare to take office regardless of party. While the Trump White House and federal agencies worked hard to meet the statutory transition planning requirements during the preelection period, Trump’s doubts about the integrity of the election and, in some instances, the lack of cooperation from his administration after the election exposed areas where norms and precedents were not enough to ensure a seamless transfer of power. |

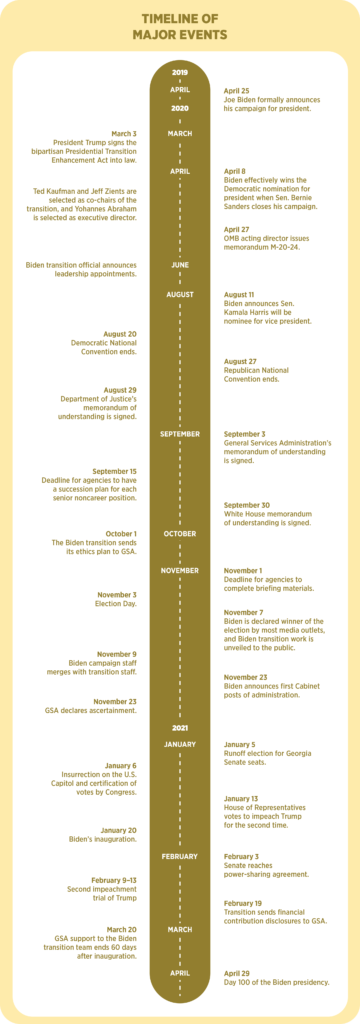

Click to enlarge |

This report offers a detailed examination of the planning and execution of the 2020–21 presidential transition from the perspective of the Biden transition team, the incumbent administration and the federal agencies, with recommendations for future transitions.

Our findings reflect significant improvements to the presidential transition process created by a series of amendments to the federal transition law since 2010, and highlight areas requiring attention:

The role of an incumbent administration in a transition is as important as the work of the incoming team. Post-election events in 2020–21 demonstrated the potential for incumbent presidents seeking reelection to impede or fail to provide support for planning by their opponent. For future elections, Congress can reduce the potential for conflict and lost time by amending the Presidential Transition Act to ensure that a delay in ascertainment—for any reason—does not interrupt critical transition assistance for viable candidates, including post-election agency briefings.

The entire appointments process needs reform. Personnel vetting and disclosure requirements are increasingly complex, and delays in the Senate confirmation process grow with each transition. Although the Biden transition had a large and well-organized personnel team, which allowed for more than 1,000 nonconfirmed political appointees with a high degree of previous governing experience to be sworn in on Day One of the new administration, only about one-third of key national security positions requiring Senate confirmation were filled within seven months of Biden taking office. We describe in further detail options to streamline vetting and security processes and improve the Senate confirmation process.

The events of 2020 and other post-election issues that have occurred during the modern era underscore the need for contingency planning by transition teams to handle a wide range of unconventional challenges. In 2000, a close election shortened the transition period for George W. Bush; in 2016, key personnel changes to the Trump transition leadership after the election required a restart from scratch; and in 2020, the disputed outcome delayed the funding and access to the agencies after the election. The early decision by the Biden transition to devote time and resources to contingency planning helped the team deal with the unprecedented obstacles. The threats posed by cybersecurity risks, foreign actors and increased political polarization will only make contingency planning even more important in future years.

To reduce disruptions and better shift from the transition to governing, transition teams should create continuity in both personnel and policy planning. On personnel, transition teams should transfer the senior staff of their hiring teams to the Office of Presidential Personnel after the inauguration. On policy, transition teams should establish procedures that ensure materials created during the transition are shared with future officeholders.

The work of experienced career officials is the foundation for a successful transition. Many departments and agencies, including most notably the General Services Administration, benefited from selecting transition directors with extensive transition experience. These directors were crucial in helping the incoming administration be prepared to govern on Day One despite the delay in the ascertainment declaration.

By requiring virtual collaboration on an unprecedented scale, the remote work environment fostered by the COVID-19 pandemic presented real opportunities and significant challenges for the transition and agency teams. The 2020–21 transition was the first to be conducted almost entirely remotely. In hindsight, many government officials and transition staff felt remote options made meetings more efficient and allowed a wider range of people to participate in the process. At the same time, employing remote workers in many different locations created increased administrative burdens and collaboration challenges.

In addition to political leaders of all parties, the media, civil society and business leaders can contribute to the health of our country by supporting the peaceful transfer of power. All voices are important in communicating about, advocating for and defending transition planning and the transfer of power through a nonpartisan lens.

Since 2008, the Partnership for Public Service has served as the nation’s premier nonpartisan source of information and resources designed to help presidential candidates and their teams lay the groundwork for a new administration or for a president’s second term. Our 2010 “Ready to Govern” report on modern transition planning provided a roadmap to formalize and improve the culture, operations and resources of presidential transitions, and we have successfully advocated for a series of amendments to the 1963 transition law that have improved the process.1

During the past decade, perceptions that it is presumptuous to “measure the White House drapes” have given way to a general—but not universal—understanding that new presidents must plan ahead to provide leadership and continuity in a fast-paced and dangerous world.

Candidates have started transition planning during the first half of the election year as a matter of course. Following an election, presidents-elect now appreciate the importance of nominating their top national security and economic advisors, and the Senate has typically offered better-than-average attention to confirming these most senior positions soon after Inauguration Day while lagging behind on subsequent appointments.

The events of the 2020–21 transition, however, brought attention to longstanding areas of fragility and point to issues that require a stronger legal foundation, the need for increased financial support for a range of transition activities, improved agency planning and a focus on reforming the appointment process. Indeed, Biden transition team co-chair Jeff Zients said the Biden team’s goal was not only to prepare the best transition ever, but to do so in the hardest transition environment ever.

This report was produced by the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition® and the Boston Consulting Group. Both organizations played crucial roles in assisting all three of the major stakeholder groups throughout the 2020–21 transition. A detailed summary of the Center’s work is available in the report entitled, “Looking Back: The Center for Presidential Transition’s Pivotal Role in the 2020–21 Trump to Biden Transfer of Power,” produced in April 2021.2

The Toughest Transition in History

Photo credit: Architect of the Capitol

Ever since George Washington handed the keys to John Adams, the peaceful transfer of power from one president to the next has been an American tradition. This critical aspect of our democracy, however, has often been quite challenging.

In 1861, Abraham Lincoln took office as southern states seceded from the Union. In 1933, Franklin Roosevelt became president during the Great Depression. And in 2009, Barack Obama became president during a major economic crisis. But none had the confluence of crises that faced the transition of 2020–21.

In the weeks following the 2020 election, filmmaker Ken Burns summarized3 the environment:

“We are in totally unprecedented territory … We are in a kind of perfect storm that in some ways outranks … the Second World War, the Great Depression and even the Civil War.”

“The inauguration occurred as prescribed by the Constitution, yet the circumstances were far from normal,” summarized the director of the White House Transition Project Martha Kumar. “With a nation scarred from the COVID-19 pandemic, a faltering economy and months of racial disturbances, followed by the insurrection at the Capitol, President Biden came into office with challenges few presidents have faced.”4

Challenges prior to the election

The largest public health crisis facing the country in 100 years began in January 2020 when the first confirmed case of COVID-19 appeared in the U.S.5 A lockdown followed in many parts of the country beginning in March 2020. By Biden’s inauguration in January 2021, the disease had killed more than 400,000 Americans.6 The pandemic and subsequent quarantine led to a global economic crisis as U.S. unemployment neared 15% and the global economy shrunk by an estimated 4.4%.7

In addition, the country was experiencing a racial reckoning following the May 25, 2020, death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. Along with a series of other police shootings of Black men and women, protests throughout the country brought the issues of race relations and police violence to the forefront.

The election occurred during a period when the country was experiencing historic levels of polarization.

A Pew Research Center survey in November 2020 showed almost nine in 10 registered voters who supported Biden or Trump worried a victory by the other candidate would lead to “lasting harm” to the country.8 The problem was exacerbated by the spread of misinformation on social media and other platforms, accelerating the spread of conspiracy theories that sowed mistrust and deepened divisions in the country.

While not identified at the time, the country faced additional overseas threats. In early 2020, Russian hackers launched one of the largest cyberattacks ever against the federal government and private companies. Later called the SolarWinds hack, the attacks went undetected for months and were not reported publicly until December 2020. The confidential data and communications of the government were breached, including at the departments of Homeland Security, State, Energy and Treasury.

Problems post-election

The events following the election, from Trump’s refusal to accept the election results to the storming of the Capitol, were likewise unprecedented. The decision known as ascertainment—the official recognition by the General Services Administration of an apparent successful candidate that allows a formal post-election transition to begin—did not occur until nearly three weeks after Election Day and about two weeks after most news organizations called Biden the winner.

A post-election transition period that was expected to be 78 days wound up being only 57 days.9 Even after ascertainment, the Trump White House and Biden transition differed in their views on the type of support an outgoing administration should provide.10 While the transfer of information was straightforward in many places, several agency officials were not fully cooperative.11 The Biden transition claimed they were not supplied with some crucial information related to national security, the budget, COVID-19 trends and vaccine preparation, and more.

The transition was further complicated by the violent insurrection on Jan. 6 against Congress as it met to officially certify Biden as the next president. The attack left about 140 police officers injured and one Capitol police officer dead.12 Four other officers died by suicide in the months following.13 One protester was shot and killed. When Congress reconvened that evening to certify Biden’s election, 147 Republican lawmakers voted to overturn Biden’s victory and made claims without any proof that the November election had been stolen from Trump. In the immediate aftermath of these events, some members of the Trump administration resigned in protest.

The control of the Senate was not decided until after the special election runoff in Georgia on Jan. 5, in which Democrats won the two races. Those victories created a 50-50 split and effectively gave Democrats control of the Senate because Vice President Kamala Harris would become a tiebreaking vote. Even though the 117th Congress was sworn in on Jan. 3, the Senate did not reach a power-sharing agreement until Feb. 3, which determined how committees and floor procedures would operate. Senate business cannot proceed in full without such an agreement, and the delay was one factor contributing to the slow pace of confirmations of some of Biden’s nominees for important government positions.

A week before Biden was sworn in, the House impeached Trump for inciting the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol, the second impeachment of his presidency. The Senate trial was held from Feb. 9 to Feb. 13, during Biden’s first month in office, further delaying the confirmation of Biden appointees. The Senate voted 57-43 to convict Trump, falling 10 votes short of the two-thirds majority required by the Constitution to convict a president.

The country had experienced presidential transitions during other times of crises, but never had such a combination of problems come together quite like it did in 2020–21.

Improving the Transition Process

Photo credit: Shutterstock

| “Current transition teams need to look at prior transitions to learn how they were managed,” explained Gail Lovelace, a former General Services Administration official who served as the government’s director of presidential transition from 2007 to 2010. “Every transition is going to be different based on a variety of factors, including what is going on at the time in our country. Learn from the past, but really look for opportunities.”14

Both laws and norms guiding transitions have improved during the past 20 years. Looking back at how the process has changed can help inform how more improvements can be made in the future. One shift has been the perception surrounding transition planning. In 2008, Republican presidential nominee John McCain accused his opponent Barack Obama of “measuring the White House drapes” and was hesitant to engage in advance planning out of superstition.15 In 2010, the Partnership wrote, “Rather than viewing early, preelection transition planning as premature and presumptuous, our nation must recognize it as prudent and necessary, and acknowledge that failing to plan for the transition can leave the country vulnerable to issues ranging from national security to the stability of financial markets.”16 |

PRESIDENTIAL TRANSITION ACTPassed by Congress in 1963, the Presidential Transition Act was created to promote the orderly transfer of power from one administration to another. The law has been amended over the years to recognize the increasing complexities of transitions. The law requires the General Services Administration to provide office space and other core support services to presidents-elect and vice presidents-elect, as well as preelection space and support to major candidates. It also requires the White House and agencies to begin transition planning well before a presidential election, benefiting both first- and second-term administrations. Another benefit of the law is that it has offered political cover for career officials so they can fulfill the needs of a potential change in administration with minimal political interference. As has been done following recent presidential transitions, Congress should examine how the law might be updated to better address the challenges of modern transitions. This report offers multiple suggestions in the recommendations sections at the end of this document. |

Thanks to laws passed by Congress and public education efforts—especially the visibility of the thorough 2012 preelection preparations for Republican candidate Mitt Romney led by chairman Mike Leavitt—transition planning is now seen less as an act of overconfidence and more as an obligation for aspiring presidents to fulfill their constitutional obligations.

For much of the country’s history, presidential transitions have been informal processes. The transition process was formalized when Congress passed the Presidential Transition Act of 1963, which has been amended four times during the last two decades.

The law clarifies the assistance an incumbent administration must provide to eligible candidates even before the election. Sitting presidents, even if they are running for reelection, must create a White House Transition Coordinating Council as well as an Agency Transition Directors Council composed of career officials. The GSA administrator must designate a senior GSA career executive to serve as the federal transition coordinator. The law has been both a guide for presidential transitions and offered political cover for career officials so they can fulfill the needs of a potential change in administration without too much political interference. The law also requires GSA to provide office space and support to eligible candidates immediately after the national political conventions.

Recent history shows that advances in the presidential transition process can happen. The transition of 2020-21 illustrated several other areas where more improvements are necessary.

The Biden Transition Team

Photo credit: Shutterstock

| Candidate Joe Biden and his transition chairs decided the key to a successful process would require a large, experienced team that improved on processes of the past and produced innovative ways to design policy. The ongoing crises the new president would face meant there was not much space for people to learn on the job.

To match the breadth of problems facing the country, the Biden transition leadership subscribed to many best practices used by previous transitions, made early decisions about how their organization would run and made some innovative choices that allowed for the successful transfer of power despite many unforeseen obstacles. |

Click to enlarge |

Preelection: Transition planning begins

March–November 2020

The Biden transition team—which later became the Biden-Harris transition team—began initial transition planning in March of 2020, about eight months before the election and 10 months before a potential inauguration—roughly the same timeframe some of the most recent presidential hopefuls began planning.

From the outset, the goal of the transition was to prepare an administration that would be able to act on the policies and promises made by the candidate. By drawing on his vast experience, Kaufman created four guidelines the transition followed throughout and became the foundation of the effort.

- The transition does nothing to hinder the campaign.

- What happens during the transition stays with the transition.

- Policies are made by the campaign, not by the preelection transition team.

- Staff for the transition and agency review teams should mirror the demographics of the country.

Among Kaufman’s first acts was to assemble a team to select transition leaders, including people who worked on President Barack Obama’s 2008 transition and advisors Biden had known for years. The group decided former National Economic Council director Jeff Zients would be the best person to oversee the transition. “We wanted somebody with lots of successful experience—not experienced in transitions, just experience in management—who was highly organized and totally discreet,” Kaufman explained.18 Zients recommended Harvard Kennedy School of Government lecturer Yohannes Abraham to be executive director and run the day-to-day operations. Abraham, like Zients, was known as a disciplined manager. Having taught a class on presidential transitions at the Kennedy School and served in senior roles in the government, private and nonprofit sectors, Abraham brought a wealth of experience to his position as the Biden team’s leader and organizer.

By that point, most of the country was already in a lockdown with stay-at-home orders due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “We had no idea how long [the pandemic] would last … We realized we needed to plan for a virtual transition, which would increase the degree of difficulty considerably,” Kaufman said.19

Many of the transition staff would later agree that having a virtual transition was, in some ways, more efficient and inclusive than an in-person effort. People living outside of the Washington, D.C., area could participate more easily, and staff members did not have to take time between meetings to relocate. Nonetheless, the early and ongoing challenges presented by the remote work environment–from maintaining security to building a cohesive team culture–required constant effort to overcome.

The transition team followed the public health guidelines related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. As with the Biden campaign, in-person transition events were intentionally limited in size and frequency. Transition staff members worked almost exclusively from home throughout the entire process. After the election, a few members of the transition team went to in-person meetings to access classified information.20

The transition officially announced the appointments of Kaufman, Zients and Abraham in June.21

Learning from previous transitions

The Biden leadership studied past transitions and uncovered several problems that had plagued those efforts. They also knew the unprecedented pandemic required innovative approaches. The transition team made several key choices that would allow them to successfully complete transition planning even during the most trying of circumstances.

Connecting transition planning with the campaign

A natural tension exists between the transition and the campaign staff. Both represent distinct teams vying for personnel, influence, and the candidate’s time and attention. Kaufman anticipated such challenges, which led to his first rule that the transition must not hinder the campaign in any way. This shaped the entire transition.

Staffing and the transition as an employer

Most organizations do not start with a small team and ramp up to a staff of thousands in the span of a few months. The Biden transition knew the creation of such an organization required innovation and room to grow. Building a culture and infrastructure that could be scaled quickly was a top priority. This meant the team needed to create clear rules on issues such as pay, health care and onboarding practices that were communicated clearly and consistently to everyone involved.

When discussing the staffing plan and how they built their culture, Abraham mentioned the importance of finding people who matched the ideals of the candidate and leadership. “We only looked at people who … really shared a sense of passion about this moment in time,” Abraham said. “Everyone we brought onto [our] teams, really at a gut level, internalized their responsibility to their colleagues on the campaign side, their responsibility to keep things quiet, to keep things to themselves and to not do anything that could in any way distract from the goings-on of the campaign.”23

This unintentionally precluded some qualified individuals from participating because they could not afford to take a leave of absence from their jobs. Some volunteers who wanted to devote a significant amount of time to the transition depended, in part, on the goodwill of employers to make it possible by allowing them to keep benefits such as health insurance while on leave.

Furthermore, ethics and conflict of interest policies applied by the transition prevented some skilled people from getting involved, especially from the technology community. Policy leaders on the transition—including DJ Patil, the country’s former chief data scientist—stated that many people could not afford to join the transition for little or no pay. They also highlighted that the structure of conflict of interest rules for the federal government were too broad which discouraged some qualified people with technical backgrounds to join the transition.

Despite the difficulties, the transition team’s leadership adopted stringent ethics requirements to signal the incoming administration’s commitment to increasing public trust in the federal government and those who serve.

Emphasizing the importance of IT security

Technology security was a top priority for the Biden transition in part because of the new threats of ransomware as well as hacking from external actors, which occurred during the 2016 election. Hackers were not just interested in stealing official information, but were also interested in personal emails and correspondence.

Integrating the transition IT systems, which were started in April, with systems used by government agencies, was a challenge. The transition team set up a comprehensive IT system months before Biden officially became the Democratic nominee. By the time the political party conventions ended and GSA was able to provide IT services, the Biden transition team had its own infrastructure in place. Even after the Biden team received access to GSA systems, the ascertainment delay created an additional set of timing concerns that complicated the process.

Creating integrated transition policy teams

Another innovation was the creation of a team focused on technology policy and implementation led by Patil and Jennifer Anastasoff, a founding member of the U.S. Digital Service. Some previous transitions grouped the challenging work of forming technology policy with their internal IT teams. The Biden transition divided those two critical functions. The team knew that the successful implementation of many policies, such as the ongoing Paycheck Protection Program passed by Congress, would be dependent on first-rate planning.

Preparing to fill as many political appointments as possible on Day One

New administrations must make about 4,000 political appointments, roughly 1,200 of which require Senate confirmation. Because the Biden transition officials were focused on confronting the challenges facing the country as soon as they took office, they sought to get more of the roughly 2,800 nonconfirmed appointees in place on the first day in office than any other administration had in their first 100 days.

| “That was basically born of our observation that we had to hit the ground running early after Inauguration Day,” Abraham said. “We wanted to make sure that our senior Cabinet officials, upon confirmation, had appropriate and adequate support … And we wanted to make sure that given the degraded capacity of some agencies … we knew that argued for having more slots filled earlier in that first term than prior transitions had invested in.”25

According to the transition, a record number of 1,136 political appointments were made on Biden’s first day in office, and about 1,500 by the 100th day.26 |

Increasing diversity in government was one of Kaufman’s four primary rules and a clear objective of the president-elect. This meant factoring in elements such as gender and geography along with racial and ethnic diversity. The transition also prioritized including representation of first-generation college graduates, first-generation Americans and disabled people.

For example, the Office of Presidential Personnel noted social media accounts complicated the vetting process during transition and after the inauguration. In addition to the process of reviewing each nominee’s taxes and employment history, the Biden White House deployed about three dozen people to review the social media history of new appointees.29

Some ethics requirements also serve to rule out otherwise qualified individuals and can play a role in hindering diversity. For example, rules on stock ownership “were written for people on Wall Street, but do not apply for people working in tech startups,” one transition advisor said. Many people involved with technology company startups receive stock as a major part of their compensation package, and having to divest those stocks is a financial challenge. Others suggested that rules regarding marijuana usage should also be revisited in the wake of changes to many state laws.

Well-intentioned ethics rules and vetting requirements have expanded so much in recent years that the process is occasionally in danger of becoming inaccessible for all but the most advantaged appointees.

The involvement of multiple overlapping forms and agencies in vetting and appointments, combined with a lack of transparency, has left appointees without a clear picture of where they stand in the process at any given time, and when they can expect to move forward. This lack of clarity prevents appointees from planning with their families and employers, and agencies from knowing when their leaders will come aboard.

A tool that tracks and displays the status of appointees in real time—and consolidates data requests—would reduce the uncertainty that clouds the appointment process, make public service more appealing for those outside government and enable better decision-making by appointees, agencies and the White House. The White House would have to champion a project that would require participation of multiple agencies. This tool would be useful for the Office of Presidential Personnel going forward and should be made available to transition teams to smooth the path for initial appointments.

Creative and risk-conscious contingency planning

Early in their planning, Biden transition leaders created a specific workstream they referred to as “unconventional challenges.” Not only would a new administration be confronting a pandemic and an economic crisis, but they felt it was important to prepare for unforeseen or unpredictable obstacles. To transition leader Kaufman, planning for risks was an obvious decision. “It’s management 101,” he said. “Any business school would tell you to plan for risks.” The team made a list of 70 potential problems before they stopped counting. At first, the team divided the challenges into three categories: challenges to the integrity of the election and validity of the results, challenges to the economy and challenges to effective governance.30

In retrospect, the contingency planning wound up being among the most critical decisions the transition team made. “I don’t know what probability … I or others would have assigned to the possibility that ascertainment would be delayed,” Abraham recounted. “But it was not a zero. And the fact that it was nonzero and it was appreciable meant that we had to have a plan for it.”31

Abraham added, “The agency review teams led by Cecilia [Muñoz] built a whole suite of programming that the agency review teams could do in the scenario where … it was post-election and that we were not ascertained, and we did not have access to the federal agencies.”32

Led in part by the transition’s general counsel, the contingency planning focused on the memos of understanding signed by the transition and considered what problems could arise in the case of a delayed ascertainment or other unpredictable events. The planning discussions determined that the most critical potential problems involved access to funding, technology and information from agencies.

To prepare for these potential problems, the team raised additional money before the election to ensure there would be adequate cash on hand if federal funding was curtailed. The team set up a comprehensive technology platform using software that could function independently of federal services. And in lieu of contacts with agencies immediately after the election, agency review teams created detailed plans to consult with former political and career officials, policy and operations experts who possessed knowledge of what was happening inside federal agencies. Talking to former officials is not as informative as speaking with current staff. But this decision allowed the agency review teams to begin their substantive inquiries as they waited for ascertainment.

Transition policy work going unused

The Biden transition was aware that in the past, some of the transition policy work went unused or unshared once the new administration took office, which affected the shift from the transition to governing. And although the Biden transition tried to mitigate this problem, it encountered similar issues.

Members of the Biden transition policy teams expressed concern that significant portions of the planning work conducted prior to the inauguration were not received by White House officials or agency leaders once they were in office. This gap required new officials to start from scratch or simply not reflect the hard work of the transition period, wasting months of innovative thought leadership and analysis.

There is no single reason for this communication breakdown. Some of the work was pre-decisional or exploratory, some was sensitive, some was likely protected due to public records requirements at agencies, and some was simply lost.

Future policy teams should establish methods to better share materials created during the transition with officials who take office, being conscious of potential barriers and designing their processes with this in mind. If content is meant to transfer to agencies, policy leads should be aware of future Freedom of Information Act or presidential record requirements up front rather than discard work at the end of the transition due to last-minute risk aversion. They also should work with appropriate counsel to understand what this may entail.

Structure of the Biden transition team

When creating the transition team’s structure, the leaders wanted to improve on previous efforts by breaking down silos and making the vetting and hiring processes more efficient. They also knew the organization needed to be agile and technologically savvy.

The Biden transition team considered May through August their “prep period” where they identified leadership, set up infrastructure and determined how the organization would function. They also created the groundwork for how policy planning for a potential Biden administration would be developed.

The team started small. However, by the time the Biden transition team was in full gear, it had about 1,500 staff and volunteers.33 The transition was led by five co-chairs including Jeff Zients, Anita Dunn, Ted Kaufman, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and Cedric Richmond, then a congressman and co-chair of the 2020 Biden presidential campaign. Executive director Abraham oversaw 13 departments.

Post-election: getting ready for Day One

November 2020 – January 2021

Once the election is finished and a winner is declared, transition planning kicks into another gear. The transition team can begin to have contact with federal agencies and receive financial and operational support from the General Services Administration. The 2020 transition was hindered by the delay in ascertainment and the refusal of the sitting president to acknowledge that a transition would occur. But the Biden transition team found ways to work around such obstacles, thanks in part to their prior contingency planning.

Ascertainment delay

The ascertainment delay was unprecedented and placed a burden of stress and complexity on the public, the Biden transition team and federal agencies. For the Biden team, it presented financial, relational and coordination delays. Some of these harms were mitigated by implementing a backup plan based on their early contingency planning.

With this foresight, and due to the mission-specific focus of transition staff and volunteers, the impact of ascertainment did not monopolize the concerns of most transition staff.

“The focus for [Biden] was standing up the incoming government, and that’s what all of us were focused on,” said Cameron French of the communications department. “I think [Biden’s] comments were limited [on external events] because we had a list of 25 things to do every day, and maybe No. 25 was worrying about the ascertainment decision.”

Still, the very practical effects of the delay were real and preventable, meriting attention from Congress and from future White House and transition team planners.

Jan. 6 attack

On the day of the Jan 6. attack on the Capitol, Biden described the events as “an assault on the citadel of liberty” and blamed President Trump for stoking the mob.35 But members of the Biden team said the reverberations from the attack did not require much change in their strategy or timeline.

“To some extent, we were like every other American watching it unfold, but were not able to intervene. There was a sitting government in place that was responsible for that,” French said.

Planning to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic

Consistent with Biden’s focus on the COVID-19 pandemic during the campaign, the transition prepared extensively to combat the virus once assuming office.

One of Biden’s first major post-election actions was to establish a COVID-19 advisory board, which included three prominent co-chairs: Marcella Nunez-Smith, a Yale physician and researcher; Vivek Murthy, a former U.S. surgeon general; and David Kessler, a former Food and Drug Administration commissioner.

Biden announced Ron Klain would be his chief of staff. Klain worked with the transition on its COVID-19 plan and was part of the Obama White House team that combated the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Klain told Politico that Biden’s view was “that information should come from medical experts so it would be seen as neutral, expert-based advice and not shaped by political considerations.”36

Other priorities were to ensure hospitals had necessary protective gear and to build a public communication campaign combatting vaccine hesitancy. “We are fully eyes-open that there needs to be a rebuilt trust in government and institutions and what is communicated to the American people, and that’s part of the discussion,” said Jen Psaki, who would later become the White House press secretary.37

In early December, Biden named several officials to lead the nation’s public health functions. He tapped Zients, his transition co-chair, to serve as the White House COVID-19 coordinator; California attorney general Xavier Becerra to lead the Department of Health and Human Services; and Dr. Rochelle Walensky, chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, as the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In addition, Biden named Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health as chief medical advisor on COVID-19.

In January, Biden announced his $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief plan known as the American Rescue Plan. To develop the plan, the transition team worked to gain access to the Trump administration’s data before and after ascertainment. Murthy said the transition team sought real-time data on metrics such as hospital bed capacity, medications in government stockpiles and vaccine distribution plans.38

The Trump administration allowed transition officials to attend the coronavirus task force meetings beginning on Jan. 11. The transition team gained access to Tiberius, the government’s vaccine distribution tracking software, in mid-January.39 While participation in these meetings and access to the system demonstrate cooperation on the Trump team’s part, both came later than the Biden team requested.40

Agency review teams

Agency review teams are responsible for collecting information about the roles and activities of each major department and agency of the federal government, and for providing insights that will be useful to the new administration as it assumes power and pursues its policy agenda.

The nearly three-week delay in the declaration of ascertainment proved especially challenging for the agency review teams. They were unable to have contact with career agency employees. However, the transition created a contingency plan for such a scenario and began interviewing hundreds of former career and appointed officials from each agency, as well as experts in think tanks, nonprofit organizations and academia. The review teams also stepped up their research efforts on publicly available information. While these efforts could not replace engagements with current federal officials, the effort helped minimize the negative impacts of the delay.

| The Biden agency review effort differed from previous transitions in two more significant ways. First, team members were selected not just for their knowledge of policy, but also for their ability to help execute policy. The teams included budget and legal advisors along with technologists who examined how technology could be used to administer programs. The organization of a nationwide vaccine distribution plan, for example, would involve technical capabilities and planning. Learning from examples such as the problematic launch of HealthCare.gov in 2013, the transition emphasized implementation and technical knowledge.

Second, the Biden transition placed a large emphasis on engaging career civil servants. The transition hired many former agency leaders and former civil servants who had longstanding relationships with career executives. Research by the Center found that nearly 76% of agency review team members previously served in government. Agency review team leaders stressed the importance of treating the civil service with respect and admiration, and incorporated these themes into onboarding and training sessions. Another priority for the transition was to include many prospective appointees on the agency review teams. Muñoz studied previous transitions and determined there needed to be effective strategies for getting information to incoming officials. |

AGENCY REVIEW TEAMS

|

“We tried hard to recruit people, both for the agency review teams as well as for the policy teams … who fit the profile of folks that would be likely to land in those jobs,” Muñoz said. “We set a goal of trying to convert more agency review team members into government officials than previous transitions.”

Integrating campaign and transition teams

An issue that plagued previous election winners has been the integration of campaigns and transition staff, who often competed for jobs in a new administration. The Biden transition planned accordingly. While members of the transition policy teams are often well-prepared to get a White House job based on their transition experience, many members of the campaign staff are also hopeful of landing such a job, which can cause tensions between the two organizations. Part of the transition team’s mitigation strategy was to reserve jobs specifically for campaign staff.

“We knew from previous transitions that moving from the campaign to the transition was uniformly a pretty uncomfortable experience,” Muñoz recalled. “We understood that a relatively small number of campaign staff were going to move over to the transition [after the election], but we tried to make sure that they had clear roles we identified with the campaign leadership in advance so they felt some sense of connection. We had specific spots reserved on the agency review teams since the agency review work ramps up right after the election.”

Integration takes place as well between the transition team and the emerging administration. Transition officials must adapt quickly as some team members are selected for positions in the administration. This involves a balancing act between incorporating new leaders, executing transition responsibilities and preparing for permanent positions. After the selection of Ron Klain as White House chief of staff, for example, he coordinated with transition leaders and assumed a more public role in speaking for the incoming administration.

Post-inauguration: transitioning to governing

Work on a presidential transition does not conclude when a new president is sworn in. While the Biden transition organization worked to shut down operations in accordance with relevant laws, some of the policy and personnel planning conducted during the official transition carried over to the first few months of the new administration.

Winding down the transition organization

Since the offboarding for a large staff would take time and resources, the Biden team began this process around Dec. 15, 2020. This included staff returning laptops and turning off access to email and other systems. On a few occasions, work was dropped prematurely, necessitating a process to “re-onboard” people. Full-time employees who were not getting a job in the administration had their health insurance covered until Feb. 1.

Sixty days after the inauguration, March 20, GSA support for the transition team ended while 18 people remained on the transition team to complete its work. Six months after the election, only a small number of people still remained working for the transition organization to handle outstanding requests and complete tax requirements.

Early executive orders and legislation for the new administration

The Biden transition identified executive orders as a critical tool to address key policy goals and signal they were moving quickly to address the country’s problems. These executive orders were written during the transition period so they would be ready to issue soon after taking office. Biden signed nine executive orders during his first day in office and 19 by the end of his third day.41 By contrast, Trump signed just one during his first three days, Obama signed five and George W. Bush did not sign any executive orders.

Biden’s executive orders included direction on preventing discrimination and advancing racial equity in the federal government’s services, programs and procurement, and several related to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. Biden invoked the Defense Production Act to bolster vaccine production and increase the availability of personal protective equipment.

In addition to planning for executive orders, future transition teams should assure their personnel teams prioritize appointees who can implement those initiatives quickly and effectively. Without such skilled appointees in place, the implementation of executive orders becomes more difficult.

Two major pieces of legislation that had been part of Biden’s campaign promises were proposed to Congress on Inauguration Day. The first was the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, also known as the COVID-19 relief package. The second was the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, which aimed to create a roadmap to citizenship for undocumented individuals and create a permanent solution for recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

The Biden administration credited its policy work during the transition along with outreach to Capitol Hill prior to Biden taking office for the early legislative action.

Slow pace of Senate confirmations

The substantial number of presidential appointments requiring Senate confirmation—about 1,200—has been an obstacle for all recent administrations to get their staff in place quickly. A reduction of the number of such positions would speed up the overall confirmation process and decrease the length of vacancies in essential positions. As the late editor of The Washington Post’s editorial page Fred Hiatt wrote, “It’s difficult to put meat on the bones of any agenda without ambassadors, assistant secretaries of state and defense for different regions in the world.”42

The Senate should also review and streamline its confirmation process, including fixing the privileged nominations calendar to make the confirmation of noncontroversial nominees simpler and faster.

Even though Biden announced more nominees for presidential appointments than previous presidents, the pace of confirmations by the Senate was still slow after he assumed office. For example, Biden announced all 15 of the primary Cabinet positions by Jan. 7—about two weeks prior to his inauguration. However, 15 days into Biden’s presidency, the Senate had confirmed only five Cabinet secretary nominees. At a comparable time, President Bill Clinton had 13 nominees confirmed, George W. Bush had 14, Barack Obama had 11 and Donald Trump had four.43

All recent presidents have faced challenges getting confirmations through the Senate, and the Biden administration suffered a similar problem even though it submitted more nominees than recent presidents. By the 100th day in office, Biden had submitted 220 nominations to the Senate, 30 more than Obama and 130 more than each of Trump and Bush. However, only 44 of those submissions had been confirmed, far fewer than the 67 confirmed for Obama.

Not only do new administrations have to get officials confirmed to leadership positions, but they must prepare those officials to do the jobs. Congressional appropriations for the 2020 transition provided GSA with $1 million for orientation activities for new Biden administration appointees. Orientation activities for new appointees—whether experienced government veterans or new public servants—can be incredibly valuable to incoming leaders as a means to set common assumptions and values, level-set on new or challenging dynamics, and increase awareness of specific substantive issues. These orientations present a unique opportunity to train incoming appointees, and agencies should consider offering orientation sessions as part of their onboarding process.

Budget delay

New presidents are required by law to submit their budget proposal by the first Monday in February. Preparing to revise and submit a federal budget is a crucial part of transition policy planning and is one of the most significant opportunities to demonstrate priorities for a new administration. The Biden administration did not release its budget until May 28, well after the statutory deadline. However, this delay is not uncommon. Trump released his first budget in mid-March while the previous three incoming presidents did not meet the deadline either and released theirs in April or May. Each of those, however, advised Congress regarding the general overview of their policies in a message submitted to Congress in February.44

The Biden administration claimed one main reason for the late release was lack of cooperation from the outgoing Trump administration’s Office of Management and Budget.

“The previous administration’s political appointees at OMB placed severe limits on the type of assistance career professionals could provide the Biden transition team, including blocking analytical work that is necessary to developing a budget,” OMB spokesperson Rob Friedlander told Roll Call.45 Transition executive director Yohannes Abraham suggested the lack of cooperation would complicate COVID-19 plans for the incoming president.46

Contrary to past practice, the Trump White House did not believe it had an obligation to help the incoming Biden team on the budget during the transition. “OMB staff are working on this Administration’s policies and will do so until this Administration's final day in office,” Trump OMB director Russell Vought wrote. “Redirecting staff and resources to draft your team’s budget proposals is not an OMB transition responsibility.”47 OMB’s sparse provision of resources and lack of analytical support did more than just inhibit the Biden team’s development of a budget. It also hindered government-wide planning for regulations and rulemaking. As Martha Coven, the OMB agency review team lead, explained, “OMB is so crucial to everything that government does that blocking our team there effectively blocked our team elsewhere too.”

Agency Preparation and Review Teams

Photo credit: Department of Agriculture/Bob Nichols

In 2020, despite major crises facing the country and the controversies that surrounded the aftermath of the election, most federal agencies followed the applicable laws and handled their roles with professionalism.

Preelection: Transition planning begins

Early 2020–November 2020

A career civil servant with more than 40 years of federal service and deep knowledge of presidential transitions, Gibert was picked because she was “experienced, honest, straightforward, transparent and knew how to do it right,” according to former Deputy GSA administrator Allison Brigati.”48

Career executives found the statutory requirements of the Presidential Transition Act, along with external communications, helpful in creating space for them to begin their work. Paula Molloy, transition lead for the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, said, “What really helped prompt us [to start with transition planning] were the GSA communications and the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition’s communications. That actually helped me work with leadership and say, ‘We must appoint someone responsible for this and we need to ensure we successfully complete each project assignment.’”

Agency transition planning gets underway

According to Gibert, GSA began planning for a potential transition at least two years before the election.49 The staff wanted to make sure they were prepared to support other federal agencies when those agencies started their own planning.

The preparations that GSA and others must make in advance of an election are extensive. GSA works closely with several agencies—the Office of Government Ethics, Office of Personnel Management, National Archives and Records Administration, and Department of Justice—that are informally known as the service providers because they support preparations government-wide for a presidential transition.

- OGE trains executive branch agency ethics officers, issues guidance to outgoing administration appointees and reviews ethics forms from prospective nominees.

- OPM creates transition guides for agency HR professionals and compiles information for the Plum Book on presidential appointments.

- NARA works closely with agency records officials and the White House to preserve all necessary records.

- DOJ must work closely with transition teams and the Federal Bureau of Investigation to process hundreds of clearances for transition team members before and after the election. DOJ typically signs two memoranda of understanding with transition teams: one after the party nominating conventions and then a second after the election.

The service providers must make these preparations without compromising their core responsibilities, which presents significant resource challenges and tradeoffs. Past transitions have appreciated the dedication of these agencies, but also experienced frustrations in the limits on capacity of these service providers.

To strengthen the service provider agencies, Congress should take several steps. First, Congress should consider additional appropriations to support a surge of personnel and resources for service provider agencies that experience increased workloads during transition years. Second, GSA would benefit from appropriations that are dedicated to its own transition needs in addition to appropriations that are given for the purpose of disbursement to transition teams. Finally, Congress should reinforce OMB’s role as a service provider to transition teams. Given OMB’s central responsibility for regulations and rulemaking across all departments and agencies, treating OMB as a service provider similar to OGE, FBI and NARA would help incoming teams develop their agendas.

The service provider agencies themselves may also consider ways to improve future transitions. One step that DOJ may consider, for example, is consolidating its memoranda of understanding with transition teams, following GSA’s example. Early in the transition process, GSA signs one MOU with each transition team that accounts for both preelection and post-election planning. Having a single agreement would expedite post-election cooperation, particularly if an ascertainment delay occurs.

Some agencies began planning for transition early in 2020. At the Department of Homeland Security, for example, Mark Koumans was appointed transition coordinator and started assembling a team and examining previous transitions as early as February. Agency transition efforts formally began on April 27 when acting OMB director Russell Vought issued memorandum M-20-24. This memo instructed the heads of executive departments and agencies to designate a senior career executive as the agency transition director by May 1.

In smaller agencies, an experienced senior career executive generally worked with a small team of two to four people. Agencies with effective transition efforts provided timely communications to keep their colleagues informed. Since much agency work is based on precedent, agencies should clearly document all the steps and procedures they use each cycle.

The agency transition directors selected for 2020 were a seasoned group. According to an analysis by the Center, about half of ATDC members worked on transition planning in 2016 while about one-third served in the same role. These transition veterans were deliberate in thinking of how best to support a first- or second-term administration.

Convening transition leaders from various agencies

There were two primary forums for agency transition leaders to convene and share information: the Agency Transition Directors Council and the Agency Transition Roundtable. Both forums met monthly and provided opportunities for agency transition directors to build relationships with their counterparts, exchange ideas, share best practices and hear from experts.

The ATDC was created by the Presidential Transition Act and is co-chaired by GSA’s federal transition coordinator and the OMB’s deputy director for management. The council includes agency senior career officials responsible for transition activities. It is required to meet at least once a year in non-presidential-election years. During presidential election years, the council meets on a regular basis starting six months before the election. In 2020, the ATDC was chaired by GSA and OMB. It consisted of representatives from 15 Cabinet departments and six other agencies, and began monthly meetings in May. During these meetings, agency transition directors discussed the state of preparations and guidance from the White House. They also conferred with former agency transition directors on best practices for transition planning and meeting requirements. The members and topics covered by the ATDC during each presidential election provide a unique opportunity to connect experienced officials throughout government with agencies that require specialized help on certain transition issues.

The ATR meetings were led by two groups outside the government: the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition and the Boston Consulting Group. The ATR met six times between June and Election Day, coordinating topics and questions with GSA. Each meeting was attended by more than 100 senior career executives from 65 agencies. Many officials stated they found immense value in the ATR meetings, especially the opportunities to hear from former agency transition directors and presidential transition team members. The Transportation Department’s transition director Keith Washington reported the meetings created helpful opportunities for “small groups where people were able to meet each other and to tap into networks.”

Although there were similarities, the ATR was able to provide opportunities the government-led ATDC meetings could not. ATR meetings were open to a larger group of agencies and people beyond the agency transition directors. ATR meetings explored how agencies could meet core transition objectives and fulfill the guidance they received from the ATDC and GSA. The experience with ATR shows an area of opportunity for future ATDC meetings that could be used to review lessons learned from previous transitions and identify possible future improvements.

Agency deliverables

Under the Presidential Transition Act, agencies are required to produce two categories of deliverables:

- Succession plans for each senior noncareer position by Sept. 15 of an election year.

- Briefing materials for new appointees by Nov. 1 of an election year.

The succession plan requirement was slightly different in 2020 than it was in 2016. Previously, the Presidential Transition Act required the head of the agency to designate a career employee to serve in an acting capacity for every noncareer position they deemed “critical” if that position were to become vacant. Legislation signed into law in 2020 required agencies have succession plans for each “senior” noncareer position.50 In both cases, agency transition directors were often unsure about which positions required succession plans. Agencies made decisions by drawing on past precedent, consulting with general counsels and asking other agencies like their own. GSA reported that almost every agency completed its succession plan by the scheduled deadline of Sept. 15.

Agencies should share their succession plans with transition teams. Considering that acting officials often remain in place for months, agencies should support these future acting officials with training, resources and support necessary for them to conduct the full scope of their responsibilities.

As Molloy of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation explained, “Being forced into an electronic process made things more efficient. [After] going through 2016, 2012 and 2008, I was used to really big binders. It was really nice to know that your final deliverables were actually the electronic documents. Once you did that … you were done, and you didn’t need a huge conference room for putting binders together.”

Scott de la Vega, the agency transition director for the Department of the Interior, added, “We made [an online] site that was secure, password protected and somewhat interactive … I was able to press a button and share the access to the entire set of materials. It took a lot of work by our IT folks … but I highly recommend that in future transitions … we continue to do that.”

Some agencies found creative ways to share information with the landing teams, the transition team representatives who interact with agency officials following the ascertainment decision. The Department of Homeland Security, for example, placed briefing materials onto specially designed iPads that were sent to members of the Biden transition team to ensure security and prevent IT complications.

Working remotely

Prior to the election, the ever-changing COVID-19 situation created a need to plan for both remote and in-person work arrangements. This added a new layer of complexity to communications between agencies.

One challenge was that the government does not share a single IT platform across all agencies. This issue impacts the federal government even beyond transitions. But the incompatibility of video conferencing, file sharing and other collaborative software proved especially problematic when time was limited during a transition period. Software that might work well for some agencies cannot be used by others for security or technical reasons. Consequently, connecting and collaborating virtually with GSA was easier for some agencies than others. Scheduling and connecting using different video conferencing software made internal coordination less efficient. Gibert and her deputy, Dorsy Yoffie, attempted to make themselves as accessible as possible to help rectify some of these issues.

Ultimately, many agency transition directors reported that while it took some getting used to, the remote working environment did not hinder their preparations. In fact, many felt remote work enabled them to be more efficient. James “Mouse” Neumeister, chief of staff of the Department of Homeland Security’s Presidential Transition Office, said, “We didn’t need to travel, move around, park and get access into most facilities. The pandemic was initially a curse, but it was then a blessing—especially following the three-week delay in ascertainment, which would have been difficult to overcome in a nonvirtual environment.”

Post-election: Agencies get a delayed start

November 2020–January 2021

The Presidential Transition Act required agencies to have transition briefing materials ready by Nov. 1, two days before Election Day, so they would be ready to support the winner of the election. No amount of work, however, could have prepared agencies for what would take place. The delay of GSA to declare ascertainment created confusion among career officials. Agency leaders were unable to share information with their employees about when the transition would begin or even to publicly acknowledge that a transition would take place. The absence of timely information and the contrast between the business-as-usual approach inside the agencies and the reality that a transition would occur on Jan. 20 placed great strain on the career workforce across the government.

Many senior leaders wanted to give clear directions to their staff, but struggled to communicate since there was no precedent for the situation.

Ascertainment occurs

GSA administrator Emily Murphy formally made the ascertainment decision on Nov. 23, three days before Thanksgiving. Within hours, Gibert and GSA connected agency transition directors with their counterparts on the Biden transition review teams. Even though it was about three weeks later than planned, the agency transition directors put their months of planning into action. The limited time was an unexpected and difficult challenge. But thanks to the advanced planning and the flexibility of many civil servants, most agencies were able to make up for the lost time and deliver the necessary information to the Biden team in a few weeks.

Agency officials added that collaboration was made easier by the presence of experienced leaders on the Biden transition review teams. Many had served recently in the agencies they were now studying and already had strong professional and personal relationships with current officials, making it easier for the two sides to accomplish what was needed in a shortened time period.

Agency transition teams presented their briefings on issues they believed a Biden administration would be interested in and on topics that they felt the new administration should know about. Most agency transition directors adopted a customer-focused approach, responding to inquiries from the Biden transition. Many agencies answered hundreds of requests; DHS, for example, recorded fulfilling about 240 requests for information. Rigorous project management was essential to ensuring no requests for information slipped through the cracks.

Several agency transition teams also played important roles in supporting appointees through the confirmation process. Some of this support came in the form of assistance to agency review teams, which were tasked with gathering information to prepare nominees for confirmation hearings.

During past transitions, agency transition directors have been called upon to support confirmation preparations at the highest levels. For example, when President-elect Obama announced his intent to nominate Arizona Gov. Janet Napolitano as secretary of the Department of Homeland Security in 2008, DHS’ transition director, Coast Guard Rear Adm. John Acton, organized flights to Phoenix for the appropriate agency staff to prepare the governor for confirmation hearings.51 This support can vary by agency, by the instincts and preferences of the incoming administration, and by the desires of the nominee, but agencies themselves can offer a wealth of experience, best practices and insight on the confirmation process and associated congressional dynamics.

While the Biden transition team agreed most agencies were fully cooperative during the shortened transition period, reports of interference from some political appointees and a lack of assistance from some agencies hindered some of the crucial work.

Working with outgoing officials

At the time they were supporting the incoming administration, agency transition teams also assisted Trump administration appointees departing government. These efforts were complicated by Trump’s refusal to publicly acknowledge a transition was going to occur. In some agencies, appointees were unable to avail themselves of standard out-processing and outgoing services typically available. Career staff typically brief outgoing appointees on separation requirements, career assistance, health insurance options and other important topics.

Scott de la Vega, who led the Department of the Interior’s transition team, described some of the problems created. “You could be hurting your own people,” he said. For a brief period of time we couldn’t give [outgoing officials] information on health insurance and other employment matters. We could not give briefing sessions previously scheduled for days after the election about post-government employment rules. If you are a young staffer and you’ve just had a baby, not knowing things like that [is a problem]. Post-government employment rules can be complicated, but several appointees at Interior could not look for jobs because they didn’t know what they would be recused from since formal ethics briefings were delayed. Not being able to start a credible job search for over two weeks created anxiety for more than a few of the political appointees.”

Policy

Consistent with the principle that there is only one president at a time, agency staff continued to advance Trump’s priorities throughout the transition period. In previous transitions, some outgoing agency heads ceased certain activities to allow the incoming administration flexibility to make its own decisions. In 2021, however, some appointees carried on as if Trump had won and initiated activities that career staff knew they would have to reverse after Biden was sworn in.

During engagements with the Biden transition agency review teams, most agencies reported that outgoing appointees did not interfere with their conversations and preferred to be briefed periodically. There were, however, appointees in several agencies who insisted on being present in every videoconference meeting. Some agency staff stated this put them in awkward positions.

The Trump White House

Photo credit: White House/Tia Dufour

Most officials in the Trump administration cooperated with the Biden transition team. However, leaders in a few prominent agencies were not accommodating. The Biden team claimed they were unable to get valuable information related to intelligence and the budget.

Ultimately, the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol became a tipping point for some in the administration as several high-level officials resigned. Liddell decided to stay on to complete the critical work of preparing for the inauguration of the new president.

Preelection: Transition planning begins

January – November 2020

Liddell was an experienced transition planner who served as executive director of the 2012 Mitt Romney transition team and co-authored the Romney Readiness Project, a comprehensive transition guide. Liddell knew it was crucial to start early. In January 2020—about a year before the next inauguration—the White House team began transition meetings and planning conversations considering two scenarios: reelection and a new incoming administration.

Planning for a second Trump term

The Trump administration prepared for a second term by focusing on two areas: policy and personnel.

Liddell led the effort and aimed to ensure that decisions would be “a continuum rather than a significant change.”52 In January 2020, he convened an offsite meeting with all the major White House deputies to discuss potential policies for a second-term administration and how those would come out of first-term objectives.

In April, the Office of Management and Budget sent an initial memo to agency and department heads providing guidance on their obligations, which formally kicked off the government’s transition process. The memo called for agencies to appoint transition representatives and outlined the requirements of the Presidential Transition Act. By May, the White House Transition Coordinating Council was set up following the requirements of the transition law. By fulfilling these requirements on time, the White House transition team wanted to signal the transition process was moving smoothly and was not being politicized, regardless of the political climate.

Liddell planned for three possible outcomes of the election: A clean victory for the Trump administration, a clean victory for the challenger Biden and a disputed election outcome. Procedures were straightforward if the outcome of the election was clear, but more complicated with a disputed outcome. Unfortunately, the scenario that worried the transition team the most became the problem they were forced to confront.

Post-election: The White House gives conflicting messages

November 2020 – January 2021

Trump’s refusal to acknowledge the results of the election created problems for the transition and complicated matters for those working in the White House on the transition.

In particular, GSA administrator Emily Murphy faced pressure to not declare Biden as the “apparent” winner.53

In the 20 days between the election and ascertainment, the Trump transition team was on hold waiting for Murphy to recognize the election result. Liddell and his staff were ready to execute a transition. During those weeks, the White House transition team considered scenarios where the transition could occur over a compressed period while making sure they were ready to go the moment ascertainment was established.

When GSA finally declared the ascertainment, the White House transition team contacted the Biden transition and granted access to agencies. Liddell and his team maintained near-daily contact with the Biden team. Together, they discussed the high-level challenges encountered by the transition. The contents of those discussions were kept confidential by both teams.

Even though Trump refused to acknowledge the election results, Liddell and Brad Smith claimed they had all the support they needed to prepare for a successful transfer of power. Smith, who served as the Medicare innovation chief, played a key role in sharing COVID-19-related information with the incoming Biden transition team. Smith stated, “Chris Liddell and [senior advisor] Jared Kushner were both very clear about what the goal was for the work we were doing, which was to give the Biden-Harris team everything they needed … Hearing that message from them every time I took them a question was really helpful and gave me confidence to push where I needed to push.”

Still, the president’s lack of acknowledgement of the election results influenced the agency transition operations even after ascertainment. Many agencies cooperated fully. However, the Biden transition team and news reports suggested some agencies—especially those related to national security and the budget—were not fully forthcoming.

Jake Sullivan, Biden’s incoming national security advisor, said the Pentagon stopped holding meetings with the incoming team on Dec. 18 for the next two weeks and did not answer dozens of written requests.54 Biden himself claimed the Defense Department was not fully cooperating on cybersecurity issues. Defense officials said both sides had agreed to a holiday pause, an assertion disputed by the Biden transition.55

Several media outlets reported that political appointees in the Trump administration were joining almost every discussion between career staff members and the Biden transition, and were monitoring conversations on key issues.56

One agency transition director explained the difficulty. “I had some career executives behind-the-scenes ask me, ‘Can I reach out to the [Biden] review team and have a discussion with them without the current administration being involved?’” the director recounted. “I said ‘No, you can’t.’ I had several agency officials reach out and ask if it was possible to have a separate discussion [without the current administration], all walk to Starbucks or whatever … The current administration at the time did not want to go in that direction and I tried to do everything in my power to make sure I was managing expectations on both sides.”

In a few instances, members of the Trump team were outright hostile. Education secretary Betsy DeVos was recorded saying career employees at the Education Department should “be the resistance” to the incoming Biden administration.57

Managing the pandemic during the transition

Since the transition was occurring amid a pandemic, both teams needed to guarantee the response to the health emergency would not be disrupted, and that the Biden administration would have the necessary tools to manage and respond to the health emergency from Day One.