Key National Security Positions Have Not Been Filled Quickly at the Beginning of Recent Administrations for Two Primary Reasons

(Photo credit: U.S. Department of Homeland Security/Benjamin Applebaum)

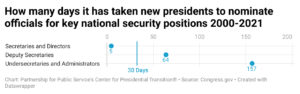

Reason 1: Recent administrations have encountered delays in nominating officials for all levels beyond Cabinet secretaries and directors.

Effective transition planning should include the vetting and naming of nominees to top national security positions prior to Inauguration Day, but vetting and disclosure requirements are increasingly complex. Recent administrations have cut through these challenges and moved efficiently in nominating Cabinet secretaries. Obama, Trump and Biden each had a person nominated or serving in the roles of secretary of Defense, Energy, Homeland Security, State and Treasury by their inaugurations.

However, the pathway to nomination has moved much more slowly on lower-level positions. During the past four administrations, it took an average of 64 days to nominate deputy secretaries and 157 days to nominate individuals for undersecretary and administrator roles. And the 2004 law did not seem to have much of an impact either. The Bush administration—which assumed office prior to the passage of the 2004 law—took an average of about 109 days for each undersecretary and administrator. The subsequent three administrations took an average of 167 days.

For context, it is important to note that each president had some officials as “holdovers” from the previous administration—meaning a Senate-confirmed official who served during a prior administration continued to serve into the new administration for a significant period of time. Eight officials from the Bush administration served into the Obama administration for at least 100 days, including Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and Secretary of the Air Force Michael Donley. While such holdovers can play an important role in maintaining continuity between administrations, the practice has been less common since. The Trump and Biden administrations held over just four officials each for at least 100 days.

(Photo credit: U.S. Secretary of Defense/Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo)

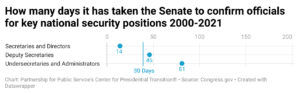

Reason 2: The Senate has moved too slowly to confirm most nominees.

The Senate confirmation process takes longer now than ever before, and not just in the national security area. The average length of time to confirm any nominee takes about twice as long than it did in the 1980s. Yet the delays in confirming leaders for national security positions leave the country vulnerable at a crucial time.

The Senate can move quickly to confirm nominees when it so chooses. Since 2000, Cabinet secretaries and agency directors have been confirmed in an average of 14 days. Almost one-third of such officials have been confirmed on Inauguration Day itself.

However, the Senate has moved much more slowly for lower-level positions. The average time to confirm a deputy secretary among key national security roles is 46 days. For undersecretaries and administrators, the average is 81 days.

The trend for the Senate is going in the wrong direction. In 2000, prior to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Senate took an average of 37 days to confirm Bush’s nominees for deputy secretaries, while undersecretaries and administrators took 36 days. Since then, the timing has increased despite the 30 day-goal set by Congress. Under Biden, deputy secretaries have taken an average of 60 days to make their way through the Senate while undersecretaries and administrators have taken 103 days.

(Photo credit: Shutterstock)

Some key national security positions have been without a Senate-confirmed official for years

The problem of filling some key national security positions does not just occur during the beginning of new administrations. Since 2000, 13 of these 46 national security positions had no Senate-confirmed official for more than two years. There was no Senate-confirmed undersecretary for Civilian Security, Democracy and Human Rights at the State Department for more than four years from January 2017—the beginning of the Trump administration—until July 2021—six months into Biden’s term. Even some of the highest-ranking security positions in the government have been without a confirmed nominee for a long time. There was no Senate-confirmed secretary of the Department of Homeland Security from April 2019 to February 2021.

There are many reasons why a particular position will be vacant or filled by an acting official for long periods of time. In some cases, vacancies may reflect an administration’s priorities or policies. In others, administrations have struggled to find people who could be confirmed in a fiercely divided Senate. Regardless of the reason, the length of time without a confirmed official in place introduces capacity and authority gaps, places a significant burden on acting officials who may be filling multiple roles, and prevents the sort of agility and long-range planning necessary to important national security activities.

As of May 2022, two high-level positions at the Department of Homeland Security—undersecretary for Science and Technology and undersecretary for Management—have been without a Senate-confirmed official for more than three years. Biden put forward nominees for both of these positions in 2021, but one was just withdrawn in May 2022 after not receiving a vote from the Senate for more than nine months while the other has been under consideration for more than six months.