The Senate created the privileged nomination process more than a decade ago, a procedure designed to speed up the confirmation of nominees for roughly 280 positions that are typically noncontroversial. Despite this well-intentioned effort, nominees on the privileged calendar are worse off today than they were before the reform was adopted.

An analysis of the data shows three notable trends for nominees navigating the privileged nomination process: 1) privileged nominees take longer to confirm now than they did before this system was instituted; 2) privileged nominees continue to take longer to confirm than nominees subject to the regular Senate confirmation process; and 3) part-time positions – the bulk of positions on the privileged calendar – take 72% longer to confirm than full-time positions on the calendar.

The creation of the privileged calendar was part of an effort to streamline the Senate confirmation process. In 2011, Congress passed the Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act which reduced the overall number of Senate-confirmed positions by 163. The Senate also adopted S. Res. 116 that created the privileged nomination process for roughly 25% of the approximately 1,200 Senate-confirmed positions. Even with these changes, the Senate confirmation process is slower now than ever before. Based on an analysis of the privileged nomination process, we recommend that:

- Congress converts more positions on the privileged calendar to presidential appointments not requiring Senate confirmation, nonpolitical career roles or agency-controlled appointments on boards and commissions.

- The Senate creates an expedited floor procedure for the privileged calendar process which would more easily allow nominees not referred to committees to be considered en bloc.

What is the privileged calendar?

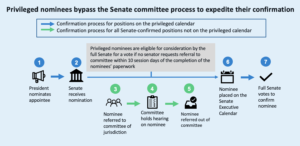

Figure 1: Privileged calendar process

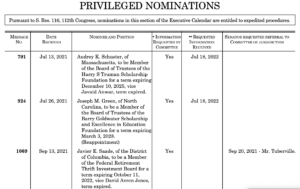

On June 29, 2011, the Senate agreed to S. Res. 116, creating the privileged nomination process that currently applies to 282 positions.1 While the process was primarily intended for part-time positions on boards and commissions, roughly 40 positions (or 14% of the privileged calendar) are full-time, including agency chief financial officers and select assistant secretaries.

The process was intended to shorten confirmations by allowing privileged nominees to bypass Senate committee consideration. After the Senate receives a nomination, these nominees can be placed directly on the privileged nominations section of the Senate’s Executive Calendar. These nominees are eligible for a vote by the full Senate vote if no Senator requests referral to committee within 10 session days of the completion of the nominee’s paperwork [See figure 1]. In 2020, the Congressional Research Service found that out of 467 privileged nominees submitted between 2011 and 2020, only 22 (or 4.7%) of those nominees were referred to committee by a Senator.

Since these positions are typically noncontroversial, the authors expected the privileged calendar would allow nominees to more quickly navigate the confirmation process. While the process allows nominees to bypass committee review, it does not provide for an expedited procedure once it reaches the full Senate. As a result, once privileged nominees are placed on the Executive Calendar, they wait alongside all other nominees for the final step of the process – a vote by the Senate. The data shows that positions on the privileged calendar are taking longer to confirm now than before its creation.

How have confirmation times changed for positions on the privileged calendar?

In order to understand the impact of the changed process, the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition studied the confirmation times of positions on the privileged calendar during the past 11 years. We also examined how long comparable positions took to get confirmed in the 10 years prior to the adoption of the procedure. Our data highlighted three main trends:

(1) The positions on the privileged nomination calendar are taking longer to confirm since the procedure was introduced than comparable positions took before the reform was adopted. The average time needed to confirm privileged nominees has increased by 47% since such positions were placed on the privileged calendar. Since this system went into effect during President Barack Obama's first term, the Senate has approved roughly 240 of these nominees, each taking on average of 251 days to confirm. That is roughly 80 days longer than similar positions took to confirm in the prior decade, when the average was 171 days.

The Senate has confirmed far fewer of these positions during the last 11 years (2011-2022) than it confirmed during the prior 10 years (2001-2011).

(2) Privileged nominees take longer to confirm than all other Senate-confirmed positions. Since 2011, privileged nominees, on average, have taken more than 75 days longer to confirm than all other nominees. That is roughly the same discrepancy that existed prior to 2011.

Simply put, the system designed to speed the Senate approval of noncontroversial presidential nominees has failed to expedite the confirmation process. This trend is part of a larger problem that has seen the confirmation times for all nominees increase during successive presidencies.

(3) Part-time positions on the privileged calendar have taken, on average, more than 70 days longer to confirm than full-time positions. Although part-time positions make up the vast majority of the privileged nomination process, the data shows that nominees for full-time positions have been processed through the system roughly 72% faster than part-time positions. This discrepancy results from the fact that part-time positions on the privileged calendar are some of the least controversial Senate-confirmed positions. As a result, they are likely to wait for confirmation behind more controversial, full-time positions

What factors may cause the delayed confirmation of privileged nominees?

The growth in the number of Senate-confirmed positions, a lower priority given to part-time positions and increasing politicization of the Senate confirmation process have contributed to the lag in confirmation times for these nominees.

|

|

|

|

|

Recommendations to improve confirmation process for positions on the privileged calendar

1) Take more privileged nominees out of the Senate confirmation process altogether: Removing appointees on the privileged calendar from the Senate confirmation process would increase the Senate’s focus on a smaller, more select group of positions. The Senate has already determined that many of these positions are noncontroversial and do not need the same level of scrutiny as standard Senate-confirmed appointees. The Partnership’s report, Unconfirmed, outlines what criteria Congress should use to determine which positions would be appropriate candidates for conversion out of Senate confirmation. These positions could be converted to political appointments not requiring Senate confirmation, nonpolitical career roles, agency-controlled appointments on boards and commissions or eliminated altogether.

For example, if a Senate-confirmed appointee reports to other Senate-confirmed individuals in more senior roles, that position may be a good candidate for conversion. For positions on boards and commissions, Congress could reduce the size of a board or commission, transfer a board or commission into a larger department or evaluate the responsibilities of part-time positions to determine whether the position needs to be subject to advice and consent.

2) Create an expedited floor procedure for the remaining positions on the calendar: The privileged calendar currently allows nominees to bypass committees but does not provide a quicker process once nominees reach the Senate floor. As a result, nominees can face long delays during the final step of the confirmation process. Because most privileged calendar positions are part-time, the Senate may have less incentive to confirm these appointees when full-time Senate-confirmed positions are also awaiting confirmation.

One way to improve this process would be for the Senate to establish a regular procedure whereby privileged nominees not referred to committees would be considered en bloc on a weekly basis while the Senate is in session. The revision could provide that a privileged nomination may be separated from the en bloc consideration if a certain number of senators sign a request for a separate vote. These changes would expedite the process from start to finish.

Conclusion

The privileged calendar was viewed as a potentially innovative solution to what had been and continues to be worsening problems for successive administrations – long delays in confirming political appointees, a declining confirmation rate and an increasing number of vacancies across the government. S. Res. 116 created the privileged calendar to provide an expedited path for nearly a quarter of these Senate-confirmed positions considered noncontroversial. However, these individuals have encountered the same issues that face all other nominees. As a result, their confirmation times have continued to increase alongside all other presidential appointees.

The Partnership for Public Service encourages Congress to consider changes to the Senate confirmation process and the privileged calendar to help future administrations more quickly fill roles that are critical for a more effective government.

and more.

Appendix: List of positions on the privileged calendar

Assistant secretaries: 16 total |

||

| Position name | Number of positions | Committee of jurisdiction |

| Assistant Secretary for Congressional Relations, Department of Agriculture | 1 | Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry |

| Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs, Department of Defense | 1 | Armed Services |

| Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Financial Management/Comptroller | 1 | Armed Services |

| Assistant Secretary of the Army for Financial Management/Comptroller | 1 | Armed Services |

| Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Financial Management/Comptroller | 1 | Armed Services |

| Assistant Secretary for Congressional and Intergovernmental Relations, Department of Housing and Urban Development | 1 | Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

| Assistant Secretary for Governmental Affairs, Department of Transportation | 1 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs, Department of Commerce | 1 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Assistant Secretary for Administration, Department of Commerce | 1 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Assistant Secretary for Congressional and Intergovernmental Affairs, Department of Energy | 1 | Energy and Natural Resources |

| Deputy Under Secretary/Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs, Department of the Treasury | 1 | Finance |

| Assistant Secretary for Legislative Affairs, Department of State | 1 | Foreign Relations |

| Assistant Secretary for Legislation and Congressional Affairs, Department of Education | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Assistant Secretary for Congressional and Intergovernmental Affairs, Department of Labor | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Assistant Secretary for Legislation, Department of Health and Human Services | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Assistant Secretary for Congressional and Legislative Affairs, Department of Veterans Affairs | 1 | Veterans’ Affairs |

Chief financial officers: 16 total |

||

| Position name | Number of positions | Committee of jurisdiction |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Agriculture | 1 | Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Defense | 1 | Armed Services |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Housing and Urban Development | 1 | Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

| Chief Financial Officer, National Aeronautics and Space Administration | 1 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Commerce | 1 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Transportation | 1 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Energy | 1 | Energy and Natural Resources |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of the Interior | 1 | Energy and Natural Resources |

| Chief Financial Officer, Environmental Protection Agency | 1 | Environment and Public Works |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of the Treasury | 1 | Finance |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of State | 1 | Foreign Relations |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Health and Human Services | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Education | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Labor | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Homeland Security | 1 | Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs |

| Chief Financial Officer, Department of Veterans Affairs | 1 | Veterans’ Affairs |

Other full-time positions: 8 total |

||

| Position name | Number of positions | Committee of jurisdiction |

| Commissioner, Administration for Children, Youth, and Families, Department of Health and Human Services | 1 | Finance |

| Chairman, Advisory Board for Cuba Broadcasting | 1 | Foreign Relations |

| Assistant Administrator for Legislative and Public Affairs, U.S. Agency for International Development | 1 | Foreign Relations |

| Commissioner, Rehabilitation Services Administration, Department of Education | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Controller, Office of Federal Financial Management, Office of Management and Budget | 1 | Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs |

| Commissioner, Administration for Native Americans, Department of Health and Human Services | 1 | Indian Affairs |

| Assistant Attorney General for Legislative Affairs, Department of Justice | 1 | Judiciary |

| Federal Coordinator, Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Projects | 1 | Energy and Natural Resources |

Part-time positions on boards and commissions: 242 total |

||

| Position name | Number of positions | Committee of jurisdiction |

| Members (5), Board of Directors, Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation | 5 | Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry |

| Members (6), Board of Directors, National Institute of Building Sciences | 6 | Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

| Directors (5), Securities Investor Protection Corporation | 5 | Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

| Members (13), Board of Directors, National Association of Registered Agents and Brokers | 13 | Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

| Members (3), Board of Directors, Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority | 3 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Members (5), Advisory Board, St. Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation | 5 | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Members (9), Board of Trustees, Morris K. Udall Scholarship and Excellence in National Environmental Policy Foundation | 9 | Environment and Public Works |

| Member (7), Board, Internal Revenue Service Oversight | 7 | Finance |

| Member (2), Board of Trustees, Federal Old Age and Survivors Fund | 2 | Finance |

| Members (3), Advisory Board, Social Security | 3 | Finance |

| Members (2), Board of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund | 2 | Finance |

| Members (2), Board of Trustees, Federal Supplemental Medical Insurance Trust Fund | 2 | Finance |

| Members (7), Board of Directors, African Development Foundation | 7 | Foreign Relations |

| Members (9), Board of Directors, Inter-American Foundation | 9 | Foreign Relations |

| Members (15), National Peace Corps Advisory Council | 15 | Foreign Relations |

| Members (8), Board of Directors, Overseas Private Investment Corporation | 8 | Foreign Relations |

| Members (8), Advisory Board for Cuba Broadcasting | 8 | Foreign Relations |

| Commissioners (7), U.S. Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy | 7 | Foreign Relations |

| Members (4), Board of Directors, Millennium Challenge Corporation | 4 | Foreign Relations |

| Members (15), Corporation for National and Community Service | 15 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Chairman, Board of Directors, U.S. Institute of Peace | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Vice Chairman, Board of Directors, U.S. Institute of Peace | 1 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (10), Board of Directors, U.S. Institute of Peace | 10 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (8), Board of Trustees, Truman Scholarship | 8 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (11), Board of Directors, Legal Services Corporation | 11 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (26), National Council on the Humanities | 26 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (8), Board of Trustees, Goldwater Scholarship | 8 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (6), Board of Trustees, Madison Fellowship | 6 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (18), National Council on the Arts | 18 | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Members (5), Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board | 5 | Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs |

| Members (11), Board of Directors, State Justice Institute | 11 | Judiciary |

| Members (2), Foreign Claims Settlement Commission | 2 | Judiciary |

- 1. The process took effect on Aug. 28, 2011. You can find the full list of positions on the privileged calendar in the appendix.

- 2. David Lewis’s analysis of U.S. Congress, Policy and Supporting Positions, various years; and Partnership for Public Service analysis of U.S. Congress, Policy and Supporting Positions, various years.

Valerie Smith Boyd

Director, Center for Presidential Transition

Troy Cribb

Director of Policy

Bob Cohen

Senior Writer and Editor

Christina Condreay

Former Associate Manager, Research, Analysis and Evaluation

Carlos Galina

Research, Analysis and Evaluation Associate

Carter Hirschhorn

Associate Manager, Center for Presidential Transition

Paul Hitlin

Senior Research Manager

Mary-Courtney Murphy

Research, Analysis and Evaluation Associate

Audrey Pfund

Senior Design and Web Manager

Loren DeJonge Schulman

Vice President, Research, Analysis and Evaluation

Max Stier

President and CEO

Betsy Super

Senior Manager, Center for Presidential Transition