This piece was originally published on the Partnership for Public Service’s blog, We the Partnership, on September 9, 2021.

By Carter Hirschhorn and Dan Hyman

Saturday marks the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, a tragedy that changed our country and the world. In 2004, a bipartisan commission investigating the attacks issued the “9/11 Commission Report,” which made 41 recommendations to prevent future terrorist attacks and strengthen our national security. One of the report’s most notable findings was that a delayed presidential transition in 2000 “hampered the new administration in identifying, recruiting, clearing, and obtaining Senate confirmation of key appointees.”

Importantly, this finding revealed our country’s flawed political appointment process and showed how slow Senate confirmations can imperil our national security. The commission’s report recommended several improvements to this process to ensure both our country’s safety – particularly during and in the immediate aftermath of a presidential transition – and continuity within government.

Appointment delays in 2001

The commission found that George W. Bush lacked key deputy Cabinet and subcabinet officials until the spring and summer of 2001, noting that “the new administration—like others before it—did not have its team on the job until at least six months after it took office,” or less than two months before 9/11. On the day of the attacks, only 57% of the top 123 Senate-confirmed positions were filled at the Pentagon, the Justice Department and the State Department combined, excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys.

New legislation since 2001

In the aftermath of 9/11, new laws addressed several recommendations highlighted in the “9/11 Commission Report.” The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 expedited security clearances for key national security positions, recommended that administrations submit nominations for national security positions by Inauguration Day and encouraged the full Senate to vote on these positions within 30 days of nomination.

The Pre-Election Presidential Transition Act of 2010 provided additional pre-election services to presidential candidates and the incumbent administration, enabling them to better prepare for a transfer of power or a second term, and to more quickly nominate key officials. The Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011 also reduced the overall number of Senate-confirmed positions by 163 in an attempt to free up more time for the Senate to confirm higher-level, policy-making roles.

Key areas for improvement in 2021

Despite these advances, the Senate confirmation process takes longer than ever; and vacancies in key Senate-confirmed positions continue to increase. For example, the Partnership’s latest report, Unconfirmed: Why reducing the number of Senate-confirmed positions can make government more effective, revealed that the number of positions requiring Senate confirmation has grown more than 50% from 1960. Partly for this reason, several positions critical to our safety and national security remain unfilled more than seven months after President Biden’s inauguration. These positions include the assistant secretary for homeland defense and global security at the Defense Department, the assistant secretary for intelligence and research at the State Department, and the assistant attorney general for the national security division at the Justice Department.[1]

The fateful morning of Sept. 11 and the subsequent 9/11 Commission Report revealed our need for a more efficient Senate confirmation process. Accelerating this process and reducing the number of Senate-confirmed positions would strengthen our government’s ability to protect the nation and serve the public. To build a better government and a stronger democracy, we must efficiently fill vital leadership roles throughout the federal workforce. That can only happen if we continue to improve the way presidential appointments are made.

[1] As of Wednesday, September 8 the Senate had confirmed Biden nominees for 27% of the top 139 positions at the Pentagon, Justice and State departments combined – excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys.

By Emma Jones and Christina Condreay

For most people, the only way to find out who is serving in the top decision-making positions in government is to reference a document called the Plum Book. Unfortunately, this document has significant procedural and factual problems and could be greatly improved.

The Plum Book remains the best source of valuable information about our senior government leaders, including names, position titles, salary information and term expiration dates. It contains information on more than 4,000 political appointees – about 1,200 of whom are subject to Senate confirmation – along with thousands of other jobs filled by senior career officials in the federal civil service.

However, the Plum Book is only published every four years. This means that information about some positions is outdated before it is even made available to the public. Even more problematic, the most recent version of the Plum Book contains numerous errors and shortcomings. Here are three of the biggest mistakes in the latest Plum Book published on Dec. 1, 2020:

1. Some agencies are omitted without explanation.

The following agencies appear in the 2016 Plum Book, but not in the 2020 edition. These organizations remain active and are funded. Combined, they have about a dozen presidentially appointed positions requiring Senate confirmation and between 60 and 100 positions not requiring Senate confirmation.

- Department of Agriculture Office of the Inspector General.

- Office of the Director for National Intelligence.

- Administrative Conference of the United States.

- Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (United States Access Board).

- Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council.

- International Boundary Commission: United States and Canada.

- Presidio Trust.

- Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board.

- The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

- Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission.

2. The Plum Book is missing positions.

Other agencies appear in the 2020 Plum Book, but are missing key positions. Agencies with incomplete position totals include the National Endowment for the Arts, the United States Holocaust Memorial Council and the United States Postal Service. Scholars at Vanderbilt University have identified additional positions that were missing from both the 2016 and 2020 Plum Books. In total, hundreds of positions are not included in the 2020 Plum Book.

3. The appendix does not match the rest of the document.

The 2020 Plum Book contains appointment information for 170 agencies, while Appendix 1 provides summary counts for 158 distinct organizations. The 12 agencies excluded from the appendix include four legislative branch agencies and the Harry S. Truman Scholarship Foundation. Additionally, the last six agencies listed alphabetically in the Plum Book are also missing from the appendix in addition to part of the White House that employs 82 people.

The 2020 Plum Book also only counts filled positions in the Senior Executive Service, a change from previous editions. This means that roughly 1,100 vacant positions out of about 8,000 of the government’s senior executives are not counted in the agency position totals listed in the appendix.

Since the Plum Book is only updated every four years, these mistakes could remain uncorrected until 2024. The Plum Book also does not include supporting methodological information or documentation of any changes made from previous editions or explanations for omissions. But this is not the first time it has been filled with errors.

Fortunately, there are several fundamental improvements that would make the Plum Book more useful. First, the information should be updated as close to real-time as possible. Second, errors should be fixed as soon as they are caught. Third, while the Plum Book is available online as a PDF and through a few other options, it should be available in a more downloadable and machine-readable format. Fourth, providing data based on the self-identified demographic information of individuals holding positions listed in the Plum Book would help shed light on how well the government is doing in attracting and retaining a diverse workforce. Proposed legislation called the PLUM Act would accomplish all these objectives.

These improvements would bring increased transparency and accountability to the federal government by helping ensure the American people know who is serving in top decision-making positions. In addition, the PLUM Act would provide timely information on Senate-confirmed positions and whether they are vacant or filled by an acting official, providing transparency and reinforcing accountability under the Vacancies Act. On June 29, 2021, the PLUM Act was reported out of the House Committee on Oversight and Reform.

Congress should pass the PLUM Act to modernize the Plum Book and prevent major mistakes from occurring in future editions of a critically important government document.

By Shannon Carroll

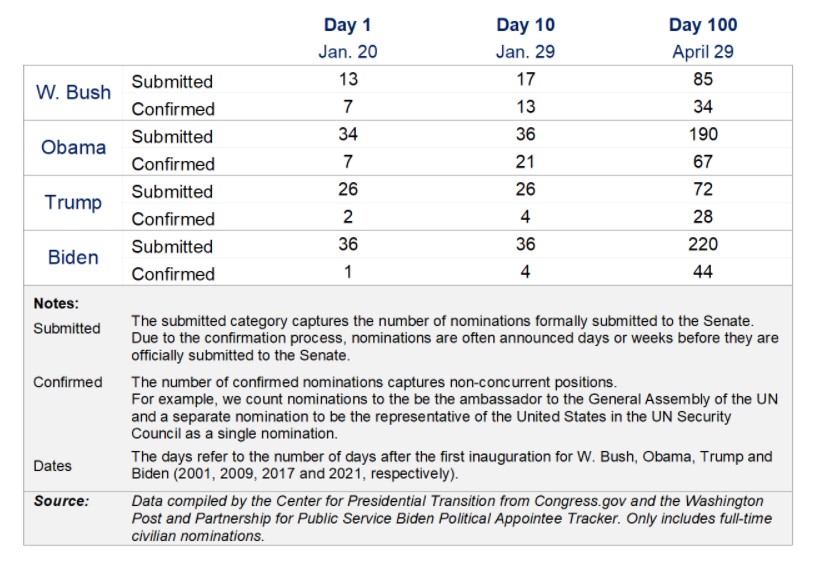

At the 100 day mark of his administration on April 29, President Joe Biden had outpaced his predecessors by appointing a record of nearly 1,500 officials to government positions not requiring Senate approval and by nominating 220 others for Senate confirmed jobs, a tribute to the extensive work that took place during the presidential transition.

But like his predecessors, Biden has been impeded by the slow Senate confirmation process that has kept him from getting key leaders in place across the government.

Of the roughly 1,200 positions that require Senate confirmation, the administration announced the selection of more individuals, and officially submitted more to the Senate, than prior administrations. In addition, the diversity and representation among the appointments is historic, and that includes the Cabinet.

However, only 44 of 220 appointments submitted to the Senate were confirmed by the 100th day. This compares to the 67 appointees confirmed by the 100th day during President Barack Obama’s administration, still a small number given the size of our government and importance of many of the unfilled positions.

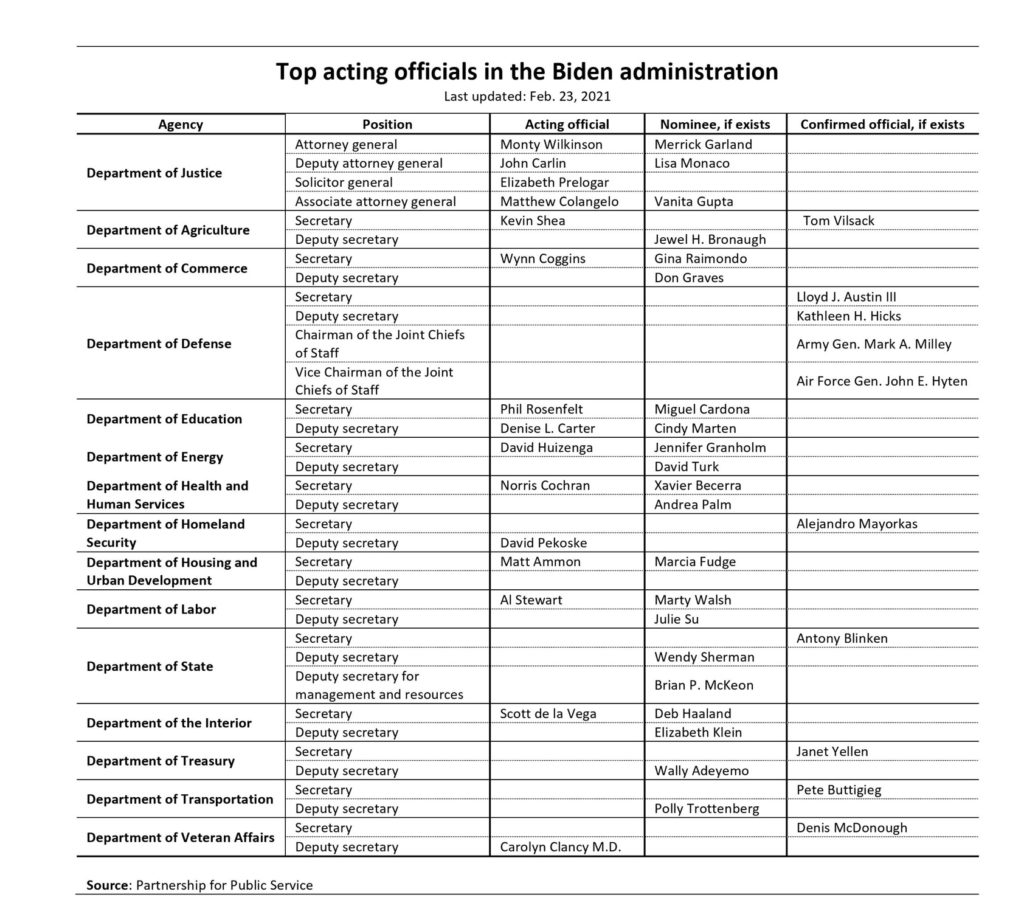

Currently, for example, Biden nominees awaiting Senate approval include the deputy secretaries for the departments of Health and Human Services, Commerce, Labor, Agriculture and Education.

Unfortunately, no administration has been able to get more than about 5% of Senate confirmed jobs filled during the first 100 days. This is largely due to a Senate confirmation process that is slow and broken. In fact, the pace of Senate confirmations more than doubled between the Reagan and Trump administrations.

While the Constitution gives the Senate the responsibility to “advise and consent” on administration appointments, the sheer number of appointees requiring confirmation combined with institutional bottlenecks has created an untenable situation that is doing a disservice to the country.

The Partnership for Public Service, which is dedicated to making the federal government more effective, is eager to collaborate with members of Congress on both sides of the aisle to improve the system, to reduce the number of political appointees, and ultimately to help presidents get qualified leaders on the job in a more timely manner so they may serve as stewards of our federal government

By Will Butler

On Jan. 20, the world watched as Joe Biden was sworn in as the 46th president of the United States. Despite all of the challenges and turmoil surrounding the election results, Biden’s presidency got off to a fast start due to extensive transition planning that began in the spring of 2020, with more than 1,100 political appointees sworn in and nine executive orders signed during his first few hours in office. The Biden team kicked off preparation for these activities nearly 10 months earlier, and the Partnership’s Center for Presidential Transition® provided crucial support throughout.

Our new report, entitled, “Looking Back: The Center for Presidential Transition’s Pivotal Role in the 2020-21 Trump to Biden Transfer of Power,” details how the Center aided the Biden team’s efforts. As the go-to expert on transition planning efforts since 2008, the Center shared key insights, historical documents, access to subject-matter experts and extensive research on nearly every key transition topic and workstream.

The Center also collaborated with the Trump White House to support their dual role: planning for a second term and executing their statutory duties as the incumbent administration in case there was a transfer of power. The Center supported career agency transition officials across the federal government, worked with Congress to make policies and processes, and created Ready to Serve, a comprehensive resource for those looking to serve as a political appointee.

In total, the Center created over 1,000 pages of new resources and provided various transition stakeholders with more than 150 historical documents. The Center connected nearly 200 subject-matter experts to share their advice with the Biden transition team, the Trump administration and career agency officials. The retrospective report offers an in-depth look at the pivotal support the Center provided—from laying the groundwork with the Biden and Trump teams almost a year ago to preparing prospective political appointees in recent months—and its role as the go-to resource for nonpartisan counsel and support for presidential transitions.

Read the full report here.

Last updated April 30, 2021 at 8:00 a.m.

Presidents are responsible for about 4,000 political appointments, about 1,200 of which require Senate confirmation. This blog includes a comparison of how Biden’s pace of appointments and confirmations compares with the previous three presidents.

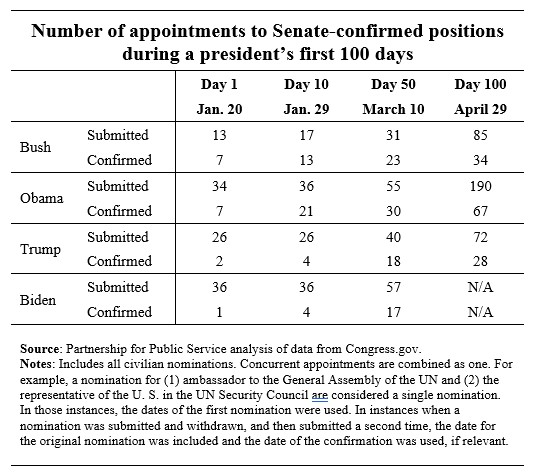

This table provides the number of nominations submitted to and confirmed by the Senate for positions in the executive, legislative and judicial branches on key dates early in an administration. Nominations for concurrent positions, like the ambassador to the General Assembly of the United Nations and the representative of the United States in the United Nations Security Council are counted as a single nomination.

For a detailed list of many key nominees and their statuses, see the Biden Political Appointee Tracker which is updated daily by the Partnership for Public Service and The Washington Post.

Nominations and confirmations by key dates

By Paul Hitlin and Christina Condreay

March 10th marked President Joe Biden’s first 50 days in the White House. One of the main tasks for any new president is to fill approximately 1,250 positions in the federal government that require Senate confirmation. Biden has submitted more nominations than his recent predecessors at a comparable time, but the Senate has confirmed fewer of those nominees.

Through his 50 days in office, Biden officially nominated 57 people for Senate confirmed positions. That is more than each of the previous three presidents. Obama nominated almost as many with 55. However, the Senate has only confirmed 17 of Biden’s picks. Each of the three previous presidents had more nominees confirmed, although President Donald Trump had only one more with 18.

There are multiple reasons behind the Senate’s slower pace. The Jan. 5 runoff election in Georgia, which decided party control of the Senate, was certainly a contributing factor. So was the second impeachment trial of Trump, the prolonged negotiation over how power would be shared in an evenly divided Senate, and a variety of other political factors. Regardless, the Senate has an obligation to act quickly to ensure that our government has qualified and accountable leadership in place, especially during times of crisis.

For current information on the status of Biden’s nominations and Senate actions, visit the Biden Political Appointee Tracker which is maintained by The Washington Post and the Partnership for Public Service.

By Jaqlyn Alderete

Ethics requirements are now essential for transition teams planning for a new administration and for appointees once a president takes office. These plans ensure that staff members do not personally benefit from their roles or promote agendas that create a conflict of interest.

The 2020 Presidential Transition Enhancement Act codifies the practice of previous transition teams implementing ethics plans that include provisions relating to classified information, lobbying, foreign agents and conflicts of interest. And once taking office, recent presidents have issued executive orders with ethics rules that govern executive branch appointee interactions with the public, provide for transparency and ensure coherence with laws regarding lobbying. If an individual is appointed to a position in a department, they must also abide by ethics rules issued by their own ethics division.

President Joe Biden’s transition team and his administration both issued ethics requirements and made them publicly available. While each plan centers on ensuring high ethical standards, there are differences which reflect the distinctions between serving on a transition team and serving in public office.

The Biden transition ethics plan called on staff members not to misuse their positions for personal benefit. It also emphasized safeguarding classified information and protecting the reputations of Biden, his running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris, and other top transition officials. The administration’s ethics pledge emphasizes restoring and maintaining public trust in government by focusing on preventing or resolving conflicts of interest.

Some of the differences in Biden’s two ethics requirements include:

- The transition ethics plan had a lobbying restriction of one year while the administration’s pledge has a two-year prohibition. Both the administration’s and the transition’s ethics rules include provisions barring individuals from engaging in matters they worked on as lobbyists or as foreign agents, but for different periods of time.

- The transition ethics plan included provisions regarding disclosure of nonpublic information while the administration pledge has no such provision. Transition team members were required to obtain authorization before seeking access to nonpublic information and pledge to not use such information for personal gain.

- The transition ethics plan restricted team members from promoting their work in marketing materials during and for 12 months after their service.The administration’s ethics pledge does not include the same requirement. However, it states that appointees should not use their positions for personal gain and advises them to avoid using or appearing to use their government position for private benefit.

- The transition plan restricts team members, their spouses and minor children from buying or selling individual stocks unless they get approval from the general counsel. Officials in presidentially-appointed positions requiring Senate confirmation are required to follow rules issued by the Office of Government Ethics regarding divestiture of investments and other financial interests.

- The transition plan stated that team members could not make any representations on behalf of Biden or then-Senator Kamala Harris, their designees, or transition team officials without authorization.The administration ethics pledge does not mention this matter.

The goal of ethics agreements for a transition team and an administration is to ensure accountability and integrity among those serving in these institutions. Individuals serving on presidential transitions and in government must understand and follow all ethics rules to ensure their work is transparent and in the public interest.

Editorial credit: Andrea Izzotti / Shutterstock.com

By Paul Hitlin

The withdrawal of Neera Tanden’s nomination to be the director of the Office of Management and Budget has left President Joe Biden with a challenge faced by the previous five presidents – an unsuccessful Cabinet-level nomination early in their tenure.

Biden becomes the sixth president in a row who has notched at least one unsuccessful Cabinet-level nomination by the end of their first two months in office. Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Donald Trump each had one, while President Barack Obama had three.

The large majority of early Cabinet nominations are confirmed. The three presidents preceding Biden – George W. Bush, Obama and Trump – announced 59 nominations combined for Cabinet-level positions within two months of taking office. Of those, 54 were approved by the Senate and five were unsuccessful.

The few who did not succeed received significant attention. For example, Trump’s initial secretary of Labor nominee Andrew Puzder was withdrawn before a Senate hearing due to concerns over financial issues and personal conduct. Tom Daschle, Obama’s first pick for secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, withdrew before a hearing due to a widely-covered tax controversy. The controversy over the hiring of undocumented immigrants for Clinton’s first attorney general nominee, Zoë Baird, was so widely covered it earned the moniker “Nannygate.” Eight years later, a similar controversy derailed George W. Bush’s first nominee for Labor secretary, Linda Chavez.

As with Tanden, most unsuccessful nominees are withdrawn prior to a Senate vote when it becomes apparent there is not enough support for confirmation. Administrations typically anticipate a candidate cannot win in the Senate and withdraw the nomination before a failed vote takes place. In fact, only one Cabinet nominee has been rejected in a Senate floor vote in the last 60 years – George H. W. Bush’s nominee for secretary of Defense, John Tower, in 1989.

In some instances, presidents have withdrawn nominations before the paperwork is officially submitted to the Senate. Of the five early Cabinet nominees named by George W. Bush, Obama and Trump who did not get confirmed, three were never actually received by the Senate.

As in the case of Tanden, failed nominations represent a temporary setback for the administration, unleash political jockeying among those promoting replacement candidates, and leave a department or agency without a Senate-confirmed leader. In this case, the Biden administration will have to proceed with its preparation of a new budget and be delayed in crafting a new management agenda without the head of OMB in place.

While this process creates complications for a president, it is one envisioned by the framers when they gave the Senate its advise and consent role on presidential nominations. Like other presidents, Biden will choose a new nominee, reach accommodation with the Senate and seek to make up for lost time.

By Drew Flanagan

Slightly more than one month into his administration, just over half of President Biden’s 15 Cabinet secretary nominees have been confirmed. At a comparable time, the previous four presidents had 84% of their Cabinet picks confirmed. In fact, President George W. Bush had his entire Cabinet in place and President Bill Clinton had all but one position filled.

The pace of confirming Cabinet secretaries historically influences the staffing of other leadership positions such as deputy secretaries and undersecretaries. Recent presidents have rarely nominated anyone to fill sub-Cabinet positions until the agency head has been confirmed. Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump collectively announced 274 sub-Cabinet nominations by the end of their first 100 days in office. Of these, only 18 or just 7% were sent to the Senate before the confirmation of their agency head.

This practice reflects deference toward the Cabinet secretaries and provides them with an opportunity to participate in the selection of officials who would work with them.

However, the current slow pace of confirmations has forced the Biden administration to operate differently. The White House has already submitted 22 sub-Cabinet positions to the Senate, 19 of which were sent before the Cabinet secretaries were confirmed (86%). Biden’s decision to take a fresh approach is likely the result of his transition team anticipating Cabinet confirmations taking longer than usual.

It is worth noting that Senate action in 2021 has been hindered by various highly unique events, including the Senate run-off election in Georgia, impeachment proceedings and negotiations over the Senate power-sharing agreement. Even so, the negative impacts of these delays remain significant, extending far beyond sub-Cabinet nominations. Without confirmed Cabinet secretaries, important decisions get postponed and government employees face uncertainty – problems that are magnified now as the country deals with the pandemic, an economic crisis and many other domestic and foreign policy challenges.

Overall, the Biden administration is ahead of the pace of nominations set by previous presidents. Biden has submitted 55 nominations to the Senate, 15% more than any of the previous five presidents at a comparable moment. Despite the high pace of personnel announcements, the Senate has confirmed just 11 of the 55 submitted nominees, including eight of 15 Cabinet secretaries.

Filling key administration jobs has taken on added significance due to the vulnerabilities posed by the crises facing our country. The sooner Biden’s Cabinet secretaries and other nominees are confirmed, the sooner they can get to work.

By Drew Flanagan, Carlos Galina and Paul Hitlin

As President Joe Biden continues to staff his administration, he has named acting officials to fill some of the 1,200 positions that require Senate confirmation – a power granted by Congress to presidents ever since George Washington’s first term. These temporary, acting officials play a vital role in maintaining continuity and providing leadership during times of change.

The rules governing the use of acting officials are found in the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998, which spells out who is eligible to be selected and how long they can serve. In most instances, the law places a 210-day limit on how long someone can execute the functions of a position, although the limit is extended to 300 days for vacancies during a president’s first year.

While acting officials are always significant, their roles may be magnified now due to the Senate’s slower than normal pace of confirming Biden’s nominees. For a detailed list of the nominees and their status, see the Biden Political Appointee Tracker which is updated daily by the Partnership for Public Service and The Washington Post.

The following is a list of acting officials named by the Biden administration for top positions at the 15 Cabinet agencies. The administration has not named acting officials for every position. The information was compiled from agency websites and public news reports.