The most fundamental function of our government is keeping us safe and, as Partnership for Public Service CEO Max Stier has said, doing so “requires extensive and thoughtful transition planning” during presidential election years.

On July 12, the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition® hosted a bipartisan discussion focused on how federal agencies can maintain security and continuity during periods of uncertainty, and the importance of responsibly sharing national security information when there is a change of administrations. The conversation led all four officials to offer deeper advice about leadership in government.

The panel consisted of Elaine Duke, the former deputy secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Karen Gibson, the current Sergeant at Arms of the United States Senate, Susan Gordan, the former principal deputy director of National Intelligence, and Essye Miller, the former acting chief information officer at the Department of Defense.

Key themes

An important theme of the event was the dynamic between the experienced career civil servants and the political appointees they serve alongside. Gordan framed the distinction as political appointees carrying out the “will of the people,” and the career officials possessing the fundamental knowledge about how to implement new policies.

To be prepared for surprises, Gibson recommended making the establishment of good relationships and linkages across agencies a top priority, stating that “even if you’re handed all the information on a platter, the toughest part is cohering as a team to deal with the crises.” Miller emphasized that career officials provide continuity in the government and she stressed the importance of establishing trust between career and political officials as early as possible.

Duke acknowledged that, even when the political climate creates barriers, civil servants “can take the first step to building that trust” and are well-qualified to do so.

Gordon said that civil servants are committed to making the government better. She emphasized that new leadership can be unnerving for career employees, but bring “real opportunity for change” and that change can be extremely positive for a new administration and the institutions of government.

The event served as a reminder of the importance of having a skilled civil service prepared to coordinate within and across agencies, and to work hand-in-hand with political leaders to help implement the policies of a new administration.

Check out the recording of this bipartisan discussion here on the Partnership’s website.

This blog post was authored by James Passmore, an intern with the Center for Presidential Transition

This piece was originally published on the Partnership for Public Service’s blog, We the Partnership, on September 9, 2021.

By Carter Hirschhorn and Dan Hyman

Saturday marks the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, a tragedy that changed our country and the world. In 2004, a bipartisan commission investigating the attacks issued the “9/11 Commission Report,” which made 41 recommendations to prevent future terrorist attacks and strengthen our national security. One of the report’s most notable findings was that a delayed presidential transition in 2000 “hampered the new administration in identifying, recruiting, clearing, and obtaining Senate confirmation of key appointees.”

Importantly, this finding revealed our country’s flawed political appointment process and showed how slow Senate confirmations can imperil our national security. The commission’s report recommended several improvements to this process to ensure both our country’s safety – particularly during and in the immediate aftermath of a presidential transition – and continuity within government.

Appointment delays in 2001

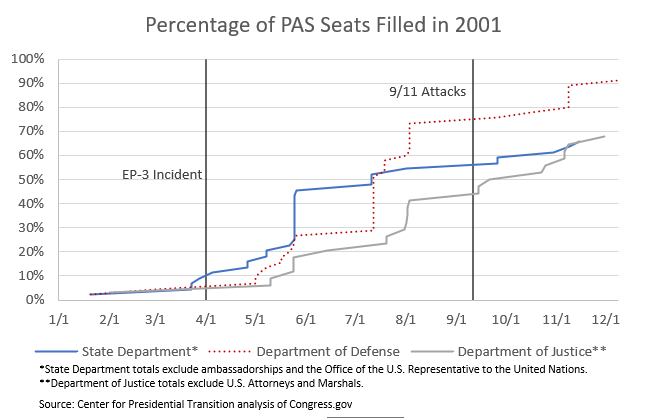

The commission found that George W. Bush lacked key deputy Cabinet and subcabinet officials until the spring and summer of 2001, noting that “the new administration—like others before it—did not have its team on the job until at least six months after it took office,” or less than two months before 9/11. On the day of the attacks, only 57% of the top 123 Senate-confirmed positions were filled at the Pentagon, the Justice Department and the State Department combined, excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys.

New legislation since 2001

In the aftermath of 9/11, new laws addressed several recommendations highlighted in the “9/11 Commission Report.” The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 expedited security clearances for key national security positions, recommended that administrations submit nominations for national security positions by Inauguration Day and encouraged the full Senate to vote on these positions within 30 days of nomination.

The Pre-Election Presidential Transition Act of 2010 provided additional pre-election services to presidential candidates and the incumbent administration, enabling them to better prepare for a transfer of power or a second term, and to more quickly nominate key officials. The Presidential Appointment Efficiency and Streamlining Act of 2011 also reduced the overall number of Senate-confirmed positions by 163 in an attempt to free up more time for the Senate to confirm higher-level, policy-making roles.

Key areas for improvement in 2021

Despite these advances, the Senate confirmation process takes longer than ever; and vacancies in key Senate-confirmed positions continue to increase. For example, the Partnership’s latest report, Unconfirmed: Why reducing the number of Senate-confirmed positions can make government more effective, revealed that the number of positions requiring Senate confirmation has grown more than 50% from 1960. Partly for this reason, several positions critical to our safety and national security remain unfilled more than seven months after President Biden’s inauguration. These positions include the assistant secretary for homeland defense and global security at the Defense Department, the assistant secretary for intelligence and research at the State Department, and the assistant attorney general for the national security division at the Justice Department.[1]

The fateful morning of Sept. 11 and the subsequent 9/11 Commission Report revealed our need for a more efficient Senate confirmation process. Accelerating this process and reducing the number of Senate-confirmed positions would strengthen our government’s ability to protect the nation and serve the public. To build a better government and a stronger democracy, we must efficiently fill vital leadership roles throughout the federal workforce. That can only happen if we continue to improve the way presidential appointments are made.

[1] As of Wednesday, September 8 the Senate had confirmed Biden nominees for 27% of the top 139 positions at the Pentagon, Justice and State departments combined – excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys.

Almost half of key national security positions requiring Senate confirmation were vacant on 9/11/2001

By Alex Tippett

A transition to a new presidential administration is a unique moment of vulnerability for our country. As President-elect Joe Biden selects his full national security team and the Senate prepares to consider presidential appointments, the experiences of previous transitions serve as cautionary tale for why slow nominations and lengthy confirmation processes can leave the nation vulnerable.

The most prominent example of how a prolonged confirmation process can undermine national security is the terrorist attacks of the Sept. 11, 2001, which occurred about eight months into President George W. Bush’s first year in office. At that time, many national security positions were vacant due in part to the shortened transition period after the contested 2000 election and the challenges associated with getting officials into Senate-confirmed positions.

At the time of the attacks, only 57% of the 123 top Senate-confirmed positions were filled at the Pentagon, Department of Justice and Department of State combined excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys. Of those officials who were in place, slightly less than half (45%) had been confirmed within the previous two months.

The bipartisan 9/11 Commission, which reviewed the causes of the attacks and its consequences, focused on the impact of the slow confirmation process. The commission suggested that delays could undermine the country’s safety, arguing that because “a catastrophic attack could occur with little or no notice, we should minimize as much as possible the disruption of national security policymaking during the change of administrations by accelerating the process for national security appointments.”

While Congress implemented a number of the commission’s recommendations, the nomination process continues to be a liability and underlines the importance of moving swiftly to confirm qualified nominees.

Confirming the Bush National Security Team

Most of Bush’s leadership at the Department of Defense took months to get into place. While Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was confirmed on Jan. 20, 2001 and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, was confirmed in late February and no other member of the DOD’s leadership team was confirmed until May.

It was during this period that the Bush administration faced its first major national security test. On April 1, 2001, a Navy surveillance plane collided with a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea. The Chinese pilot was killed in the collision and the American crew was taken into captivity. Over the next 11 days, a tense standoff ensued. While the crisis was eventually brought to a peaceful close, Wolfowitz and Rumsfeld were the only Senate-confirmed members of Bush’s DOD team, with the third and fourth ranking appointees confirmed on May 1, 2001—a full month after the incident began.

By the time of the 9/11 attacks, the Senate had confirmed a total of 33 DOD officials. Two-thirds of those officials had been on the job for less than two months. According to the 2000 Plum Book, there were 45 positions at DOD requiring Senate confirmation, leaving 12 important jobs empty on 9/11.

In an interview with the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, Stephen Hadley, Bush’s deputy national security advisor, suggested the slow pace of nominations undermined the administration’s ability to develop a response to the threat posed by the al-Qaeda terrorist group responsible for 9/11. “When people say, ‘Well, you had nine months to get an alternative strategy on al-Qaeda,’ no, you didn’t. Once people got up and got in their jobs you had about four months.”

Empty seats and a slow nomination process also hurt other parts of the Bush administration. Michael Chertoff, who served as head of the Department of Justice’s criminal division on 9/11, recalled, “We were shorthanded in terms of senior people….we essentially had to do double and triple-duty to pick up some of the responsibilities that would have been taken by others who were confirmed.”

Following a bitter five-week struggle, John Ashcroft was confirmed as attorney general on Feb. 1, 2001. His deputy, Larry Thompson, was confirmed on May 10, along with Assistant Attorney for Legislative Affairs Daniel Bryant.

Excluding U.S. marshals and attorneys, DOJ had 34 Senate-confirmedpositions in 2000. But Just 41% of those jobs were filled on 9/11. Half of those 14 officials—including then FBI Director Robert Mueller–were on the job less than two months before the attacks.

Bush’s State Department, supported by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, moved faster than other committees in the early days of the administration, but then slowed its pace. Before June, the State Department filled 20 of 44 Senate-confirmed positions, excluding ambassadorships. On 9/11, just 24, or 55%, of the 44 positions at the State Department were filled.

Conclusion

In light of these delays, the 9/11 commission recommended that, “A president-elect should submit the nominations of the entire new national security team, through the level of undersecretary of Cabinet departments, not later than January 20. The Senate, in return, should adopt special rules requiring hearings and votes to confirm or reject national security nominees within 30 days of their submission.”

Both the Senate and the Biden team should work to meet this standard. And while the Senate should carefully scrutinize every nominee, it also should recognize that unnecessary delays could undermine the ability of the new administration to respond to the threats we currently face and those that are unexpected.

By Alex Tippett

One of the most important components of the transition from one president to the next is the sharing of national security information. New administrations need to be aware of the threats facing the country and what option they have at their disposal.

Each of the last three administrations took substantive steps to ensure their successors were fully prepared. Much of this work was done by career officials in various Cabinet agencies and in the intelligence community, but in recent years outgoing White House officials and national security staff have participated.

In general, an outgoing White House prepares memos and hosts in-person briefings for their replacements. Both the George W. Bush – Barack Obama and the Obama-Donald Trump transitions included preparedness exercises to simulate real-world national security scenarios. With the passage of the Edward ‘Ted’ Kaufman and Michael Leavitt Presidential Transitions Improvements Act of 2015, such exercises are now required.

The following are examples of how the last three presidents prepared their successors.

2000-2001: Clinton-Bush Transition

According to George W. Bush’s National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley, President Bill Clinton’s administration relied primarily on written memos and several in-person briefings. The Clinton team held briefings conducted by National Security Council staff along with a limited number of principal-to-principal briefings with senior Bush officials on threats posed by al-Qaeda and the North Korean missile program.

2008-2009: Bush-Obama Transition

The outgoing Bush administration put a heavier emphasis on principal-to-principal briefings. These included meetings attended by both the incoming and outgoing secretaries of State, national security advisors and White House counsels.On the Monday following the 2008 election, Bush personally briefed President-elect Obama on ongoing covert operations.

The Bush team also relied heavily on mid-level staff. They prepared about 40 memos on specific national security concerns beginning eight months prior to the election. Meetings with members of the Obama security team began after Thanksgiving.

The Bush administration also left contingency plans for a variety of possible scenarios, and organized two tabletop exercises where outgoing members of their national security team paired up with their incoming counterparts. Roughly 50 senior officials attended. The first was held in December and focused primarily on the NSC and best practices for foreign policy decision-making. The second, conducted on Jan. 13, simulated the response to a terror attack.

On Inauguration Day, the two teams met in the Situation Room to discuss an immediate terror threat, Iran and the war in Afghanistan.

2016-2017: Obama-Trump Transition

The Obama White House followed a similar model as they prepared for Donald Trump’s transition team. National Security Advisor Susan Rice briefed Trump’s choice for the position, Michael Flynn, four separate times. The Trump team experienced personnel issues and challenges securing security clearances, delaying the first contact between Obama NSC staffers and their counterparts until Nov. 22.

These in-person briefings were supplemented by 275 briefing papers. Several, however, had to be rewritten to exclude classified information because of problems with security clearances on the Trump team.

On Jan. 13, the Obama national security team and Cabinet hosted a preparedness exercise for their counterparts in the incoming Trump administration. This exercise included a simulation exploring how the federal government might respond to a pandemic.

Stephen Hadley held key national security positions in three Republican administrations before working on the George W. Bush transition in 2000-2001 and serving as Bush’s national security advisor. Kurt Campbell is an expert on East Asian affairs who served in the Clinton and Obama administrations, and co-authored, “Difficult Transitions: Foreign Policy Troubles at the Outset of Presidential Power.” In this episode of Transition Lab, Hadley and Campbell join host David Marchick to discuss their experiences during presidential transitions and their concerns about the potential fallout from 2020 election. They also offer advice to Joe Biden’s transition team and those planning for a second term for President Trump.

[tunein id=”t157938388″]

Read the highlights:

Marchick asked Hadley how national security transitions have changed since the 1970s.

Hadley: “There’s been enormous improvement. …I came into the office the day after the [1976] election and I went to my file cabinets where I had all these classified papers. …They were all empty because these [had] become presidential records and [were] taken off to the presidential library. [Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter’s national security advisor] showed up with no documents, no paper and no staff. …I think we’ve gotten a lot better at developing the art … of transitioning from one administration to the next.”

Marchick asked Campbell to describe his transition into the Department of State after the 2008 election.

Campbell: “The State Department has it down to a science. You’re assigned a young officer, you’re checked in, he or she brings you readings every day [and] you have careful meetings you go through. …You talk a little bit about what’s expected in terms of what your role and mission would be. …It had a quality that was a little bit like going through orientation, but I found it extraordinarily interesting.

Hadley explained how he worked closely with President Clinton’s national security team during the 2000-2001 transition to the Bush administration.

Hadley: “…We took [National Security Advisor] Sandy Berger’s terrorism group … and basically said, ‘Stay on, be part of the Bush administration, keep doing what you’re doing to defend the country. We’re going to probably relook strategy and take some different approaches, but in the interim, keep doing what you’re doing to keep the country safe.’ I think that is important so that you’re not standing down a capability in a transition, but you’re able to continue to do those operational things where the country might be vulnerable.”

Hadley described the relationship between political appointees and career employees in a new administration.

Hadley: “Political employees are supposed to intermediate between the political agenda that has come out of the election, and the expertise and judgment that is inherent based on the experience of the permanent government. …It’s not that the deep state is subverting the political appointees. They’re supposed to actually live in a certain amount of dynamic tension. That’s how our system has been designed. I think it’s served us well, but … is not understood well by a lot of Americans today.”

Hadley and Campbell discussed their concerns about the 2020 transition

Hadley: “I think … China [and] Russia don’t want to do anything that looks like they’re intervening in our election in a decisive way … I do worry about once the votes are in. …It looks [like] we’re going to be in a period of fairly extended uncertainty as to who has actually won this election with a lot of contested lawsuits and contested ballots being recounted. …I’m more worried about a country trying to take advantage of us during that kind of period.”

Campbell: “I tend to agree with Steve. …You don’t realize how much of our transition is built on a degree of goodwill. When [Jim Steinberg and I] wrote [our] book, the worst that we could imagine was something like the Iran hostage crisis, the Taiwan Strait issue. But I think the real issue this time is not the threat externally.”

Marchick asked Campbell and Hadley to offer advice to Democrat Joe Biden’s transition team and those planning for President Trump’s second term.

Campbell: “Simpler is better. The key [for Biden] is to… focus on the right people. Build your teams. Make sure you understand what you’re trying to achieve. Have a few general policy aspirations laid down, but understand that really detailed plans that stretch out beyond what the eye can see are unlikely to be valuable to the incoming team.”

Hadley: “If the president is re-elected, I would say, ‘Mr. President, you were elected to be a disruptor in chief. …Your second term is an opportunity to be a builder in chief. Don’t be afraid to change personnel, to bring in people who can help you build on the foundation of the first term.’ For the Biden team, I would say, ‘Don’t think that you’re coming in and writing on a blank sheet of paper. You’re going to have a lot of the same problems that your predecessors had. There are a lot of good things that your predecessors did [that would] be smart [to] build on and make … your own. Don’t be afraid to do that.”

By Thomas Kean and Lee Hamilton

Presidential transitions are a time of great vulnerability for our nation, with a significant turnover in national security personnel occurring when the nation may be facing a foreign policy crisis or an adversary willing to cause significant trouble. Many of the laws and norms that presidential transitions follow today were put in place based on lessons learned in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

The independent, bipartisan 9/11 Commission, which we headed, examined the transition of power in 2001 from Bill Clinton to George W. Bush. We found, among other things, that the Bush administration, like others before it, did not have its full national security team on the job until at least six months after it took office.

Since a catastrophic attack can occur with little or no notice as we experienced on 9/11, we concluded that the government must seek to minimize disruption of national security policymaking during the change of administrations. In exploring this issue, our report made a series of recommendations to protect the nation from national security threats during a presidential transition.

Our proposals were adopted by Congress largely through the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004. The post 9/11 provisions have been integrated into the process for all transitions since and include:

- The designation of a single federal agency responsible for all security clearances. This task was originally given to the National Background Investigations Bureau at the Office of Personnel Management, and in April 2019 was moved to the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency.

- A requirement that the outgoing administration provide the incoming administration with a “detailed classified, compartmented summary” of national security threats, major military and covert operations, and pending decisions on possible uses of military force.

- A recommendation that the president-elect submit the names of candidates for high-level national security positions (through the level of undersecretaries of Cabinet departments) to the FBI as soon as possible after the general election, and that the responsible agencies conduct the background investigations necessary for the appropriate security clearances.

- A nonbinding sense of the Senate resolution calling on the president-elect to submit national security nominations to the Senate prior to the inauguration, and that all of those received prior to that date will receive a vote by the full Senate within 30 days of submission.

- The ability of each major party candidate to submit requests for security clearances for prospective transition team members who may need access to classified information to carry out their responsibilities. The law requires that necessary background investigations be completed by the day after the conclusion of the general election.

To be truly effective and help protect our nation from national security threats during and soon after a presidential transition, our outgoing and incoming leaders must be cooperative, take these requirements and best practices seriously, and act in the best interests of the nation.

Thomas Kean, a former Republican governor of New Jersey, and Lee Hamilton, a former Democratic congressman from Indiana, served as chairman and vice chairman, respectively, of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States.

Women are vastly underrepresented in leadership roles within the federal government and in national security fields. In this Transition Lab episode, Jamie Jones Miller, a former principal deputy assistant secretary of defense for legislative affairs, and Nina Hachigian, a former U.S. ambassador to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, talk to host David Marchick about their own careers in government, how they handled uncomfortable situations and the importance of bringing more women into leadership positions. Both women are members of the Leadership Council for Women in National Security, an organization dedicated to improving gender diversity in the national security field.

[tunein id=”t156025561″]

Read the highlights:

Marchick asked how Miller felt when she was the only woman present when decisions were being made.

Miller: “I was aware of it. I was aware I was the only woman in the room. That carries with it a certain burden. You want to perform well because you’re carrying the weight of all of the other women who want to be in the room and who should be in the room…And then I start to think about how I get more women…at the table. So I’ve made it. Great. I’m aware of it, but how do I open the door for others?”

Marchick asked how the women handled situations when male colleagues were dismissive. “How would you approach it to reduce tensions, but also stand your ground?”

Hachigian: “It helps to have some seniority and to be older. I wouldn’t suggest to younger women to just let it go…I think men don’t often realize what they’re saying can be offensive. It’s partly educating your colleagues to become allies.”

Miller: “It is not just the responsibility of the woman in the room to point that out or to correct the behavior. It is the responsibility of everyone in the room to build that culture of awareness and to point out behavior that is not appropriate and not productive or not welcome in the workplace.”

Marchick asked about the work of the Leadership Council for Women in National Security and how the organization hopes to get more women in important federal government positions.

Miller: We are compiling a database of women who are qualified for the most senior Senate confirmed roles. We want to be sure that we have a women of color. We’re also putting together advice about how (an administration) can hire diverse teams, some of the tricks of the trade. And I’m holding a series of webinars for women who are interested in advice about the appointments process.”

Marchick asked what the data show regarding organizations that have diverse workforces.

Hachigian: “The data show that diverse groups in leadership are more creative. They’re more innovative. They’re more likely to avoid group think. Women in Congress are judged to be as or more effective than their male colleagues, for example. And in the private sector, we have all kinds of data that show literally that firms are more profitable and that their turnover is less when there are women in management. But the point is that if you have different points of view to bring, you’re likely to get better results.”

Marchick asked about Mitt Romney being ridiculed during the 2012 presidential campaign for saying he had “binders full of women” when in fact he was making a concerted effort to find qualified women to serve in his Cabinet and other important government positions.

Miller: “Knowing what we know today, it is a best practice…to be intentional about finding a diverse slate of candidates. I have to give Romney credit for that. It sounds like there was the game plan and a process. Unfortunately I think `binders full of women’ became a quote that everybody seemed to be using and throwing around.”

Marchick asked Hachigian if she had advice for young women seeking mentors.

Hachigian: “Older people who have had some experience love to talk to younger people about their careers and really love to help. And so it really is just a matter of asking for some time to talk through your career, what you’re looking for in life and to ask advice and then just to keep up those relationships. That most often happened for me with people I’ve worked for and who I’ve kept in touch with, but it could be a professor or others.

Marchick asked Miller which parts of the government have done a good job promoting women and creating more opportunities and which have not?”

Miller: “Capitol Hill is a great place for women, especially today in that there are a number of congressional staff organizations dedicated to helping grow women professionally. My experience in the executive branch is limited to the Department of Defense. The most senior women in the department made a very concerted effort to get to know the younger political appointees and staff members, but those things were all led internally. We had to make those things happen.”

Marchick asked Hachigian about the opportunities for women at the State Department.

Hachigian: “I do think they’re trying, but as far as I can tell, the number of women in senior management hovers around 30%, so it’s not great. There’s no pipeline problem…People are entering the Foreign Service at about a 50-50 ratio. It’s just that they (women) fall out of the system for a variety of reasons. I think they’re trying, but we need to see more progress.”

Marchick noted that the CIA conducted a diversity study several years ago and found gender parity for entry-level jobs, but anemic numbers for those with 10 years of experience. He asked what causes women to leave.

Hachigian: “I think there’s a variety of reasons…It could be a sense that they’re not getting promoted and so they feel like this is a dead end. For some, they’ve encountered serious problems of harassment or assault. For some, it’s just being overlooked or not being heard. I think for some there’s the problem of balancing childcare responsibilities. There’s not good leave parental leave policies at all.”

Former Undersecretary of Defense Michèle Flournoy shares insights from her experience running the Agency Review team for the Obama transition and serving as Undersecretary of Defense. Flournoy also discusses the challenges associated with transitioning during an ongoing conflict, and the underrepresentation of women in national security.

Listen, rate and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher and TuneIn.

[tunein id=”t138085399″]

Read the highlights from the episode:

Dave: “So when you started your career, did you think you were going to be a trailblazer for women in the national security space?”

Michele: “I didn’t set out to be that, but I did find myself from the beginning in rooms where I was the only woman. I started my work working on nuclear issues, nuclear weapons, nuclear arms control and nuclear proliferation. And it was sort of the, the gray bearded priesthood and me in a lot of my early jobs. When I did have a chance to hire a team, I really tried to bring in a team that looks more like America and that had a greater diversity of background and perspective and experience to help us all make better decisions in the national security space. You’ve had female secretaries of state, but never a female director of a head of the defense department. It’s gotten better, but it’s still one of the least progressive areas in terms of gender opportunities.”