This week’s episode of Transition Lab features three leaders from the Partnership for Public Service. One is special guest host Loren DeJonge Schulman, a national security expert who spent 10 years at the Defense Department and National Security Council, most recently as the senior advisor to National Security Advisor Susan Rice during the Obama administration. Currently, she serves as the vice president of Research and Evaluation at the Partnership. Joining Schulman is Max Stier, the Partnership’s president and CEO, and David Marchick, director of the Partnership’s Center for Presidential Transition, who previously held several positions in the Clinton administration and worked as an executive at the Carlyle Group. In this episode, Stier and Marchick discuss the Center’s work, their concerns about the 2020 transition cycle and why transitions have improved in recent years.

[tunein id=”t158272785″]

Read the highlights:

Max Stier discussed why the Partnership launched the Center for Presidential Transition.

Stier: Transitions were historically Groundhog Day exercises. There was no learning system, no resource that someone could go to and learn how to do this better, [and] no guidebook. …Pretty much every campaign understood that job number one was to win the election [and was] not willing to invest significantly in any effort that jeopardized that work. Campaign leaders would not do transition planning for fear that they would be accused of measuring the drapes.

Stier explained how transitions have improved during recent election cycles.

Stier: Every cycle, the knowledge base has gotten larger and the transition preparation has gotten better. It really begins in 2012 with the Mitt Romney transition. The “Romney Readiness Project” led by Mike Leavitt and Chris Liddell … moved the ball forward in a very dramatic way. …They were willing to raise the flag that [transitions were] something that was not to be done in the dead of the night. …In 2016 we saw not just a single challenger doing this kind of aggressive transition planning, but we saw the entire field thinking about that.

Loren DeJonge Schulman asked about the center’s recent transition work

Stier: We created, with the help of the Boston Consulting Group, a playbook for agencies to understand how they should best prepare. This last cycle, we recognized that there was also a transition that took place between an incumbent president’s first and second term. In each cycle, we build on what we know and help make [transitions] better.

David Marchick: We did a lot of work to understand the change between a first term and a second term. …If you look at the top officials across government, almost half of them half leave between the day the president is sworn in for a second term and six months later. …We’ve [also] had a much more significant public education campaign about the importance of transitions. …This podcast, for example, [has] been downloaded 50,000 times. That’s incredible how kind of a geeky subject like transitions could be of interest to a broader population.

Stier and Marchick discussed their biggest concerns about the current transition cycle.

Marchick: The peaceful transition of power—as [filmmaker] Ken Burns talked about on our podcast—is one of the bedrocks of American democracy. …So, obviously, talk [by President Trump] about not recognizing the will of the American people is troubling. …I’m hopeful that the rhetoric will tone down, but it makes everybody nervous. …[My second worry] is just the small things: will technology work, will security clearances be granted [and] will the Senate be able to act with speed to confirm people.

Stier: The biggest worry for me is making sure that whoever is president next is ready to govern on day one. …The lift is so large that it is scary to think about what’s required. That, to me, is the core issue here: will the next leadership team be ready to address [our] … complex problems immediately?

Stier explained how career employees help ensure smooth transitions.

Stier: We have a government that is largely run and staffed by career professionals. Someone like Dr. [Anthony] Fauci [from the National Institute of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases] is a prime example of someone who has spent his career developing an incredible expertise and then serving the public over many, many decades. …The nature of the government’s authority to deal with the problems that we have today requires fewer political appointees, so that we have more expertise in decision-making roles. I think the most important thing that a new political team—or any political team—can do is to connect well with the career workforce.

Marchick described how future administrations might organize better transitions

Marchick: What’s happened with the evolution of the [Presidential Transition Act of 1963]… is that a lot of the post-election activities were moved to pre-election. …I think that more of post-election activities … can be accelerated in the same spirit. I [also] think that there can be more money. Right now, a transition costs somewhere between $8 to $10 million. …Having more money earlier will give the candidates the ability to hire people, give them healthcare and have a professional staff leading up to the election.

Stier outlined some steps that new administrations can take to govern effectively from day one.

Stier: I think investing, first and foremost, in people who understand large organizational management issues [is critical]. …There is a tendency for administrations to bring in lots of smart policy people. They already exist in government. You don’t actually need them. You need people who can deploy the resources—that amazing career workforce— against the problems of the day. Point number two would be to build a relationship very early on with the career workforce—recognizing that it begins the transition [and] that the agency review process is really an onboarding experience for a new administration. Third would be to work across the silos. One of the big issues that exist are that today’s problems don’t respect the legacy lines that make up the formation of our government. Something like the pandemic or any other big issue … actually requires many agencies, a relationship with Congress, inter-governmental activity [and] public-private relationships. And I think that modernizing the rules of government will be fundamental here as well. …The last major reform of [federal] talent rules was over 40 years ago. We still have a pay system that comes from 1949. …We need to truly invest in a more modern government if we’re going to deal with the problems of today and tomorrow.

By Alex Tippett and Troy Cribb

During election seasons, the status of political appointees in the federal workforce come under increased scrutiny. Under all recent presidents, some political appointees have attempted to become civil servants — a process commonly called “burrowing in.”

Unlike political appointments, civil service positions do not terminate at the end of an administration. Conversion therefore allows political appointees to stay in government after the president who appointed them has left office.

These kinds of conversions inevitably create concerns. Supporters of an incoming president may be suspicious of individuals hired by the previous administration. More broadly, some fear conversions can violate the merit system principles that govern hiring in the federal civil service.

The hiring process for civil servants is designed to promote a professional, apolitical workforce and to prevent discrimination, political favoritism, nepotism or other prohibited practices. To ensure these rules are followed, the Office of Personnel Management reviews requests to move a political appointee into the civil service. This review is designed to prevent improper conversions while providing talented individuals with the opportunity to join the civil service.

How does OPM conduct oversight?

While OPM has reviewed conversions since the Carter administration, the process has changed over time. Currently, agencies must submit a request to OPM whenever they seek to hire a current political appointee or one who has served in a political position within the last five years. OPM conducts multi-level reviews of each application to make sure the conversion follows federal hiring guidelines.

If OPM believes a conversion violates federal hiring laws or regulations, it may reject the conversion. If OPM finds the agency’s conversion attempt violates the federal government’s prohibited personnel practices, it may refer the issue to the Office of Special Counsel for investigation.

On occasion, agencies have converted political appointees without going through the OPM review process. In those cases, OPM retroactively reviews the conversions and issues any necessary corrective actions, which can include re-advertising the position. Recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the firing of an appointee who had converted to a career position without an OPM review.

OPM’s procedure is not laid out in statute. Instead, existing laws and regulations broadly empower OPM to protect the civil service’s merit system. Individual OPM directors have interpreted this authority differently, with the rules tightening over the years. Previously, agencies only had to file a request for a smaller subset of political appointees and only for conversions taking place close to an election. OPM’s current regulations require that every conversion receive approval.

Congress also created specific reporting requirements for conversions. The Edward “Ted” Kaufman and Michael Leavitt Presidential Transitions Improvements Act of 2015 requires that OPM submit an annual report to Congress detailing the conversions. During the final year of a presidential term, these reports must be submitted quarterly.

How common is burrowing?

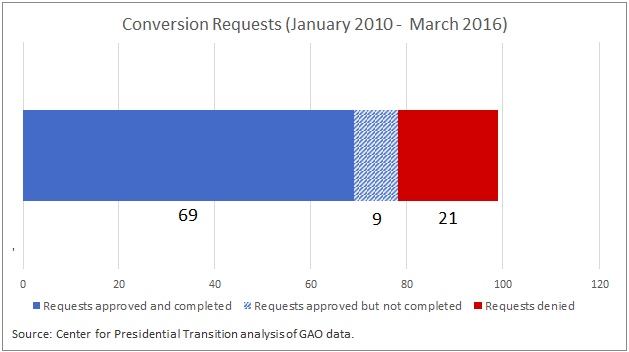

Investigations by the Government Accountability Office suggest that conversions are relatively rare. According to GAO’s most recent report in 2017, OPM received 99 conversion requests from January 2010 to March 2016. For context, during that period, the federal government hired about 100,000 people every year into full-time permanent positions.

Of those 99 requests, OPM approved 78, suggesting that most conversions followed proper procedure. The GAO found no reason to disagree with OPM’s assessments.

Of the 78 requests approved by OPM in the latest GAO report, only 69 were carried out. Occasionally, an applicant will decline to take the job after it is offered to them.

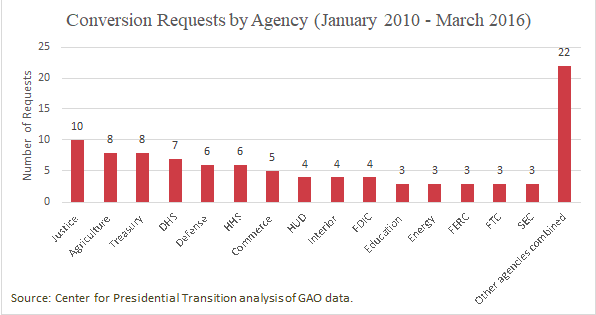

A relatively small number of agencies have accounted for a large portion of conversion requests. Between January 2010 and March 2016, approximately 10% of requests were initiated by the Justice Department. The top five agencies—Justice, Treasury, Defense, Agriculture and Homeland Security—accounted for nearly 40% of the conversion requests filed.

Some agencies have occasionally failed to request permission from OPM before carrying out conversions. There were seven instances of this cited by the GAO. When this occurs, OPM carries out a post-appointment review as soon as it becomes aware of the conversion.

Conversions themselves also tend to increase immediately before an election. While available data is incomplete, 47 conversions occurred in the final year of President George W. Bush’s presidency, up from 36 the previous year. At least 19 occurred in President Barrack Obama’s fourth year, up from 11 the previous year. GAO’s 2017 burrowing report does not include the final months of Obama’s administration or the entirety of the Trump administration.

Additional public data would be helpful

While the law requires OPM to report instances of burrowing to Congress, neither the agency nor the House Committee on Oversight and Reform or the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs have made the information public. Doing so is in the public interest and could help guard against potential abuses.

Agency review—the process of informing new administrations about the work of the federal government’s various departments—is a critical aspect of presidential transition planning. In this episode of Transition Lab, host David Marchick speaks to Lisa Brown, co-chair of agency review for the 2008 Obama-Biden transition team. Marchick and Brown discuss how this process works, why it is so important and the critical role played by career staff.

[tunein id=”t157435366″]

Read the highlights:

Marchick asked Brown why agency review is vital to presidential transitions.

Brown: “When [presidents] actually start governing on Inauguration Day, [agency review teams help ensure] they are ready to hit the ground running….The agency teams collect … critical information that the [president-elect] and his or her senior key advisors need to make strategic policy [as well as] budgetary and personnel decisions.…You don’t want gaps when one president leaves and another one comes in….You want to make sure that when the new [administration] comes in, they have the information they need to handle the crisis of the day.”

Marchick asked why career staff are so important to the agency review process.

Brown: “If you’ve ever worked in the government, you realize how critically important career employees are. They are in these agencies [and] they’re the ones who know how to get things done. You need them to be your friends. You need to be collaborating with them. The worst thing that you could do during agency review is to go in and alienate the career staff because you will find that it is much harder to get things done when you take office.”

Marchick asked how career staff tend to view agency review teams.

Brown: “I have found that career employees are professionals and they are accustomed to a change in political administration….They care about the mission of their agency. They care about the work that they’re doing. So they do want to partner with you to get that work done.”

Marchick asked Brown about her experience working with the Bush administration in 2008.

Brown: “President [George W.] Bush and his team in the White House really set the tone … for collaboration. They wanted to ensure that it was as seamless a transition as possible. This was after 9/11, so they had a real sense of responsibility to the country.”

Marchick asked Brown to discuss what she learned from spearheading agency reviews after the 2008 election.

Brown: “You need to anticipate demand for your work product quite early. The pre-election work that you do is vital….Post-election, you really do want to get people into the agencies very quickly so that you get that information fast to inform policy and to inform the personnel, particularly [during] confirmation hearings….Really think about how [to] best integrate policy teams with the agency review teams….I think you really want people [on the agency review teams] who are … familiar with the president-elect’s policies…..You [also] have to think about [creating] a structure with enough redundancy that your critical work continues … [even if] … somebody [takes on] a new role.”

Marchick asked Brown to describe how Joe Biden should handle the agency review process if he wins the election, but has an abbreviated transition.

Brown: “[A shorter post-election transition] puts a premium on engaging people who have worked in the government before. That is not to say that you don’t want fresh blood when you actually enter office on nomination day and after … You absolutely want a mix of new people and previous experience….Democrats have been out of power for not yet four years. There’s a lot of knowledge that people have that will still be relevant.”

Author Michael Lewis shares insights on the coronavirus pandemic and stories from “The Fifth Risk.” Lewis discusses the critical role federal employees play in managing the crisis, and his advice for presidential transition teams. Lewis also outlines the importance of effective government management, both in times of crisis and times of normalcy, and why we need to rethink what we’re told about the career officials running our federal government.

Listen, rate and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher and TuneIn.

[tunein id=”t140780123″]

Read the highlights:

Dave: “When you were writing about government workers, it seems like a boring subject to write about – people that work in the government. There are stereotypes about them as bureaucrats and slow-moving. What were your observations when you met people that were longtime career federal officials?”

Michael: “They were extraordinarily mission-driven, extraordinarily focused, passionate about the things they cared about. They were all moving and important characters, and easy to make a swing on the page because they cared so much about something that mattered so much, to which much of the country was completely indifferent or oblivious. I thought of them as our greatest patriots. It was as if you had a military that was off fighting and dying in a war without anybody acknowledging it.”

Dave: “Having written a whole book about transition, you’ve spent a large chunk of time on it. What advice would you have for the Biden or Sanders team on what they should be doing and how seriously they should take a transition planning effort?”

Michael: “It should be the number one priority, especially given what we’re living with now and what crisis might emerge between now and then… The biggest thing you’re being handed right now is this giant toolbox. A lot of the tools are broken, some of the tools are missing. But it’s all you’ve got. You can fill that toolbox up pretty quickly if you’re ready to go on day one, so the advice I would give them makes it a huge priority. No partisan litmus tests, the filter is not are you Democrat or Republican. The filter is, do you know what you’re talking about? Do you understand the subject? Do you have management ability?”

Lewis emphasized the importance of federal employees and the expertise they bring to their jobs.

“If you think you know what a federal government worker is, maybe you think again. When you actually meet the people doing the jobs, you think, ‘Thank God they’re there.’”