Blog

September 26, 2024

Presidential appointments are hard to track – and growing

Every new president faces the management challenge of filling out the leadership ranks of federal agencies with more than 4,000 presidential appointees. The most senior of those positions must go through an increasingly difficult and lengthy Senate confirmation process. While figuring out how many positions require Senate confirmation would seem to be straightforward, getting a precise count is actually quite difficult.

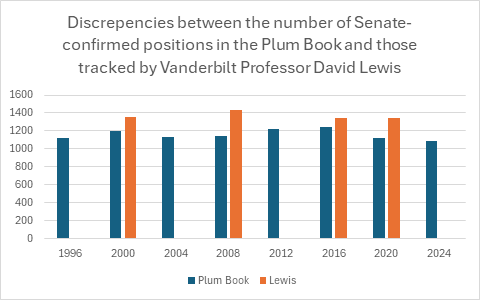

For years, the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition® has written that new presidents generally fill more than 1,200 such positions. By contrast, Vanderbilt Professor David Lewis—one of the leading authorities on presidential appointments—has compiled a list of 1,340 Senate-confirmed positions. Why the discrepancy? Shouldn’t there be a single, straightforward number?

In actuality, getting a single number is quite difficult. The primary reason is that there are many positions that are “on the books” and eligible to be filled with Senate-confirmed officials, but have not been filled for years. In other words, the best available count is that there are 1,340 eligible Senate-confirmed positions, but recent administrations have not filled all of these jobs and have instead appointed people to serve in slightly more than 1,200 positions.

Furthermore, the existence of 1,340 Senate-confirmed positions on the books – more than commonly understood – underscores the need for greater transparency and reporting. The government’s “Plum Book” listing political appointees and other top officials has traditionally been produced every four years and has been characterized by numerous omissions and other incorrect information. In 2022, Congress passed the PLUM Act, requiring the Office of Personnel Management to create and annually update a website listing such positions— a positive first step. However, more should be done to ensure that Congress and agencies provide more timely transparency when new positions are created or when positions are changed.

Determining the number

To arrive at his detailed list of 1,340 Senate-confirmed positions at the beginning of President Joe Biden’s presidency, Lewis cross-referenced multiple sources. These included the U.S. Government Policy and Supporting Positions book (often referred to as the Plum Book), reports from the Congressional Research Service, information from Congress’ official website Congress.gov, and the Partnership for Public Service’s political appointee tracker. Lewis’ list is the most detailed and accurate compilation available.

The last few presidential administrations, however, have not filled all 1,340 positions. Although the numbers change by administrations, slightly more than 1,200 of these positions have actually been filled in recent years. Some positions that are “on the books” have not been filled for decades. For example, the Peace Corps Advisory Board has 15 possible Senate-confirmed positions according to CRS reports. But no one has been nominated for any of those positions since 1992. Some positions have been kept vacant for policy reasons. There has not been an ambassador to Syria for the past decade since diplomatic relations between the countries ended.

The following sections provide additional details into why counting positions is not a precise endeavor.

The existing sources of information are inaccurate

The Plum Book has consistently undercounted the number of Senate-confirmed positions. In the 2020 Plum Book, Lewis found that 276 Senate-confirmed positions were missing. The Center for Presidential Transition found at least 10 agencies were omitted completely.

This number of missing positions is likely even higher based on information provided on the PLUM website in March of 2024, where only 1,093 Senate confirmed positions were listed—far less than the 1,340 positions included in Lewis’ list. The vast majority of the positions missing from the new Plum website are from part-time boards and commissions. OPM relies on agencies’ self-reports to identify Senate confirmed positions. Therefore, when agencies are under-resourced or inactive, OPM may not receive a timely report and omit these agencies from their accounting.

The second governmental source of information is a series of reports from the Congressional Research Service. CRS put out seven reports on the number of Senate-confirmed positions between 2003 and 2021. While CRS’ accounting of positions tends to be more accurate than the Plum Book, the reports do not include the nearly 200 ambassador positions, one of the largest classes of Senate-confirmed appointees.

Other challenges related to counting positions

Beyond inaccurate or incomplete reporting—and the existence of positions that have not been filled for years—there are several other reasons why a precise accounting of Senate-confirmed positions is difficult to achieve.

- Congress creates new Senate-confirmed positions: While the Senate added a provision in a 2011 resolution that required Senate committees to explain the justification for the creation in legislation of any new position to be appointed by the president, committees rarely comply with this requirement. Therefore, new positions are difficult to identify and might not be known more widely until a nomination is submitted. For example, Congress created a new organization in 2022 called the Great Lakes Water Authority that included a role for a Senate-confirmed co-chairperson, but no one was nominated to that position until May 2024.

- Some appointees serve in multiple positions at the same time: It is not uncommon for Senate-confirmed appointees to serve in multiple roles at once. When Steven Mnuchin was confirmed to be Treasury secretary in 2017, he was also serving as governor of the International Monetary Fund along with several other positions. Such dual roles are common with ambassadorship positions, as an ambassador may serve in their role for multiple countries or organizations.

- Some agencies have caps on the number of Senate-confirmed positions, but no specific assignments, which gives the agencies flexibility regarding titles and assignments: By statute, some agencies are assigned a number of Senate-confirmed positions without specific titles. For example, the Department of Defense is allowed to have 19 assistant secretaries. In early 2024, DOD established three new assistant secretary positions including the first ever assistant secretary of Defense for Science and Technology. This did not increase the number of assistant secretaries at DOD, but complicates the tracking of how positions change over time. Additionally, presidents may choose to not to use the full allocation, reducing the total number of positions they decide to fill.

- Changes to positions and titles over time: For years, the U.S. has had a single ambassador to both New Zealand and Samoa such as Tom Udall, who was confirmed in late 2021. In 2023, the Biden administration announced that Samoa would get its own resident ambassador and nominated James Holtsnider in May 2024. This means that a single position that was previously held by one person would now be split into two separate positions.

Opportunities for Increased Transparency and Reform

The vast number of Senate-confirmed positions and the growing difficulty of the Senate confirmation process result in presidents and the Senate focusing more time than ever on processing nominations. This also means that many important agency leadership positions remain vacant for lengthy periods, without adequate transparency into which positions are vacant or who performs the role in the absence of a Senate-confirmed leader.

The difficulty in coming to a full accounting of Senate confirmed positions suggests a need for more consistent and accurate government reporting. While the new PLUM Act database will make reporting more frequent, agencies and OPM have more work to do to ensure that more timely and accurate information is provided. And while the PLUM Act requires only an annual update of the information in the database, as OPM makes continual improvements to the database, it should aim for – and Congress should support – a system that provides as close to real-time transparency as possible.

The Senate also should consider stronger mechanisms to enforce the requirement that committees justify the creation of any new Senate-confirmed position. Additionally, the Senate could ensure that there is a public report at the end of each session of Congress on the total number of new Senate-confirmed positions created, so the new confirmation responsibilities being placed on both the presidency and the Senate can be fully understood.