This blog was updated on February 4, 2021.

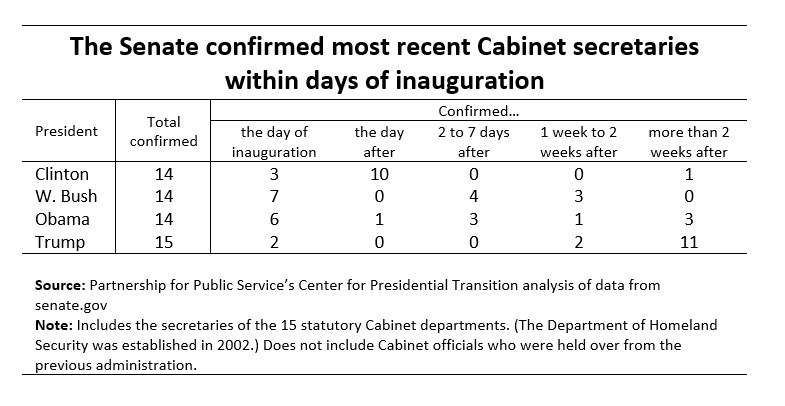

Fifteen days into President Joe Biden’s administration, the Senate has confirmed just five of his 15 statutory Cabinet secretary nominees. At a comparable time, the Senate had confirmed 90% of the Cabinet secretaries for Presidents Clinton, Bush and Obama combined.

By Paul Hitlin

Choosing 15 officials to fill their Cabinet is among the most important decisions new presidents make. The Senate plays a crucial role in considering and confirming those nominees. This year, the Senate is taking longer than it has for most other new administrations. At this time of multiple concurrent global and national crises, having a well-qualified Cabinet has taken on a new sense of urgency.

Fifteen days into Joe Biden’s presidency, the Senate has confirmed only five of 15 Cabinet secretary nominees. At a comparable time, President Bill Clinton had 13 nominees confirmed, President George W. Bush had 14 and President Barack Obama had 11. The official Cabinet consisted of 14 positions until 2002 when the Department of Homeland Security was established, and the Cabinet expanded to 15. Each president has the option to expand their Cabinet with additional members, but those positions are not part of the Cabinet as established by legislation. The Senate has confirmed one of Biden’s expanded cabinet of 23 officials – Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines.

The delays are not due to the lack of speed of Biden’s announcements. The official beginning of Biden’s transition was hampered by the delay in ascertainment – the formal decision made by the General Services Administration which triggers the government’s official preparation for a handover of power. However, Biden still announced nominations quickly. He publicly named 12 of his Cabinet choices by the end of 2020 and all 15 by Jan. 7, 2021 – about two weeks prior to his inauguration. In fact, Biden announced more nominations for Senate-confirmed positions during the time between his election and inauguration than any other president-elect.

The Senate delays began even before Biden was sworn in. The Senate can hold hearings for nominees prior to the president taking office to speed up the confirmation process. All of Clinton’s Cabinet secretary nominees had a preliminary hearing prior to Inauguration Day. The same was true for all but one of Bush’s nominees and 11 of Obama’s 14. By contrast, only five hearings were held for Biden’s picks prior to his inauguration, all of which took place the day before Biden was sworn in as president.

The confirmations of President Donald Trump’s initial Cabinet nominees took longer. Only four of his choices were confirmed within two weeks of his inauguration. However, Trump’s experience represents the exception rather than the rule. Trump’s transition team changed leadership immediately following his 2016 election, which slowed the vetting of candidates. Additionally, Trump announced nominees for secretaries of Veterans Affairs and Agriculture just days before his inauguration. Trump’s first choice for Labor secretary withdrew and other nominees did not have their paperwork completed or faced various controversies.

The reasons behind the Senate’s sluggish pace in considering Biden nominees are unclear. The Jan. 5 runoff election in Georgia, which decided party control of the Senate, is certainly a contributing factor. So is the impending impeachment trial and the prolonged negotiation over how power would be shared in an evenly divided Senate. The delayed ascertainment and refusal of the Trump to acknowledge the election results were additional factors that served as disincentives for the Senate to move forward with Biden’s nominees.

Regardless, the Senate has an obligation to act quickly to ensure that our government has qualified and accountable leadership in place, especially during times of crisis.

Now that a power-sharing agreement has been reached and committee leadership is becoming clear, the Senate has an opportunity to accelerate its consideration of Biden’s nominations. Precedents set by previous transitions suggest the Senate can – and should – move faster to fill critical vacancies so that government can serve the public effectively.

By Emma Jones

Every president is responsible for making about 4,000 political appointments, including members of the Cabinet, senior agency leaders, White House staff and lower-level appointments. Despite the importance of these jobs, there is no up-to-date source of information about who holds these positions, which jobs are vacant or the status of Senate confirmations.

To address part of this problem, the Partnership for Public Service and The Washington Post launched a webpage in December to track more than 750 of President Joe Biden’s Senate-confirmed political appointments. Positions in the Biden Political Appointee Tracker include Cabinet secretaries, deputy and assistant secretaries, chief financial officers, general counsels, heads of agencies, ambassadors and other critical leadership jobs.

For the first few months of Biden’s term, the Partnership will update the tracker on a daily basis.

Most of the information regarding nominations and the Senate’s confirmation process comes from Congress.gov, the official website for federal legislative information. We also rely on the “United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions,” known as the Plum Book, that is published by Congress every four years and includes information about Senate-confirmed positions. We also rely on information on resignations and informal appointee announcements from publicly available sources such as news stories and government websites.

This isn’t the first time the Partnership and The Washington Post have collaborated. In December 2016, we launched a similar tracker to follow the progress of President Donald Trump’s nominees to key Senate-confirmed positions. This tracker provided timely data illustrating how the Senate confirmation process has slowed to a crawl, with the average confirmation taking twice as long under Trump as it did during President Ronald Reagan’s administration. Data on the Trump administration appointees will remain accessible.

The Partnership recommends presidents fill the top 100 Senate-confirmed positions by the end of April – if not sooner – with an additional 300 to 400 by the August recess. By Inauguration Day, the Biden transition team had announced 52 nominees for Senate-confirmed positions – more than each of the previous three presidents. Now, it is the Senate’s responsibility to expedite confirmation of qualified nominees.

For the next four years, the Biden Political Appointee Tracker will serve as an important accountability tool to keep the public informed about the status of important, Senate-confirmed government jobs.

On the final episode of Transition Lab, David Marchick is joined by guest host Yamiche Alcindor, the White House correspondent for the PBS NewsHour and a political contributor for NBC News and MSNBC. As one of America’s leading journalists, Alcindor covered a transition like no other, one marked by a global pandemic and an economic recession, a racial reckoning, a president’s attempts to overturn a fair election, and an attack on the Capitol.

In this episode, Alcindor interviews Transition Lab’s regular host, David Marchick, about this historic period. Marchick, director of the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition, describes how the Trump and Biden teams approached this transition cycle, how the delay in ascertainment and Capitol insurrection impacted the transition, and how this transition stacks up against previous ones.

Coming soon! Season two of the Partnership for Public Service podcast. This is the last episode on the 2020 transition, but the podcast will return later in the year with a new focus. Stay tuned.

[tunein id=”t160354938″]

Read the highlights:

Marchick discussed how the Biden team prepared for an uncertain transition cycle.

Marchick: “[The Biden team] anticipated almost everything. …It anticipated a delay in the outcome of the election because so many people would vote remotely or by mail; it anticipated a decent likelihood of a delayed ascertainment; it anticipated the impact of an uncooperative president and parts of the administration; and it anticipated a lack of cooperation from certain agencies. …For each of these risks or potential challenges, [the team] built a mitigation strategy.”

Marchick assessed whether agencies cooperated with the Biden team.

Marchick: “Most agencies kicked into high gear once ascertainment was made. They wanted to work with the Biden team, do what was right for the country and implement the law. …Certain agencies—the Defense Department and the Office of Management and Budget—simply just didn’t want to help. …With those agencies, there was real damage done. That damage was ameliorated by the fact that President-elect Biden had so much experience and his team had so much experience. …But it’s still really unfortunate that there was a delay and I think it hurt the country.”

Marchick described how the Capitol insurrection impacted the transition.

Marchick: “There’s only 78 days [between Election Day and Inauguration Day]. Because of the delayed ascertainment, the Biden team only had 57 days. And because of the entire episode on the Capitol—not just on Jan. 6, but in the days leading up to it—[the team] lost another week or 10 days. So that brings the transition down [about] 45 days, which is about the same as George W. Bush had because of the delayed Florida outcome. …[The delay] further slowed the Senate process, which was already slow because of the Georgia [Senate] elections, and it impeded the Biden team’s ability to get people confirmed. …[The riot] shocked the nation, and I think we’re seeing the impact of that today.”

Marchick talked about the pace of Biden appointments thus far.

Marchick: “[The team] built a machine, a personnel machine. …Ron Klain, the White House chief of staff, [has] appointed more than twice as many officials to the White House staff than any other previous president at this time. …President-elect Biden [has] nominated 52 [Senate-confirmed officials]. The previous record was 42 by President Obama. …[The team also] had 1,100 [non-confirmed officials] sworn in by Inauguration Day. That is more than Obama and Trump had combined on Day 100. The personnel team has been fantastic and highly productive.”

Marchick compared this transition to previous ones.

Marchick: “You can’t say this is worse than 1860 when states seceded and [we approached] the Civil War. …In 1932, [there was] the Great Depression. We had bank runs in 25 states, Hitler came to power and Hoover did nothing. Both Roosevelt and Marriner Eccles, who was the head of the Federal Reserve, begged Hoover to call a bank holiday—to stop the banks from running and to stop people from losing their homes and their savings—and Hoover refused. That was a pretty bad transition. But as Ken Burns said [in an earlier podcast], no shots had been fired, nobody had been killed, no arms had been raised in any previous transition. So I would say that this one has to be somewhere between 1860 and 1932, ameliorated by the fact that the Biden team was so experienced and so buttoned up. It was a bad transition this year.”

Marchick outlined several reforms that would strengthen future transitions.

Marchick: “I think there are a few things the Congress should look at. For ascertainment, there has to be a lower standard for starting the process. We could have close elections again (actually this was not really a close election) and we could have contested elections again, but the president-elect and the challenger need access to the services and support from the GSA and the government earlier. I think that the challenger should get more money for staffing and everything should be moved up earlier. …78 days is really not enough to get started on Jan. 20. I’m confident that Congress will look at that and … improve the laws.”

Chris Liddell is the Trump administration’s leading transition expert. A deputy chief of staff, he previously served as executive director of the Romney transition team and helped author The Romney Readiness Project, a comprehensive presidential transition guide. In this episode of Transition Lab, Liddell joins host David Marchick to discuss the good, the bad and the ugly of the 2020 transition. Liddell talks about managing a delayed post-election transition, his experiences working with the Biden team and how he reacted to the recent attack on the Capitol.

[tunein id=”t160220623″]

Read the highlights:

Liddell described his approach to planning for a second Trump term.

Liddell: “The first area that I wanted to focus on was on policy. …In January 2020, we had an off-site [meeting] with all of the major deputies here at the White House and set down not only the policy objectives for 2020, but [also examined] how they would flow into 2021—in particular, some of the most significant legislative ideas. …I [also wanted to] think about how we could structurally change the White House to make it significantly more efficient.”

Liddell described how he helped agencies plan for a Biden victory.

Liddell: “In April of last year, we sent out an initial memo to agency and department heads providing guidance on what their obligations were. …We worked with the GSA in particular, which was then working with agencies to put together the briefing books and all of the requirements that we would need once the election happened. So we had these main markers and below the surface of those markers, we were just working away steadily with career people to make sure that we were as ready as possible. We tried to emphasize that despite the politics out in the open, the transition side of things should continue as normally as possible.”

Liddell explained how the delay in ascertainment affected his work.

Liddell: “That was one of the most frustrating periods I’ve ever seen. We were just on hold, we couldn’t do anything. …[GSA Administrator] Emily Murphy was in a terrible position for that period of time. We were literally sitting on our hands, having done all the work but not being able to do anything. …We need to look at a solution where the incoming administration can get access to a lot of the things that it needs as a result of the Transition Act, regardless of where the politics and the dispute associated with the election are. …We should have legislation that allows a provisional ascertainment to occur so that an incoming administration [and] the president-elect can get security briefings for a lot of the time-sensitive issues regardless of whether the formal election has been settled or not.”

Liddell discussed whether agencies cooperated with Biden officials during the transition.

Liddell: “Over 90% of the agencies and components went about the job really well. …There were some reluctant people, but I rang them up and basically appealed to their better side, and we managed to smooth it over. …There were some agencies that I think were uncooperative. And I tried my best to do [fix those situations], but I didn’t really have the teeth to do it. …It’s an unusual situation to have the outgoing administration in charge of the transition to the incoming one. That relies to some extent on goodwill. And when goodwill is absent, it’s hard to actually make [agency review] happen.”

Liddell described how he reacted to the recent attack on the Capitol.

Liddell: “I was in the West Wing working on transition matters when it all broke. I saw it on the television screen at the same time as everyone else. I was horrified initially and heartbroken afterwards. The event … was a disaster for the country [and] from the transition point of view, it made everything exponentially more difficult.”

Liddell explained why he chose not to resign after the attack.

Liddell: “I respected that some people decided that this was their opportunity to leave. I came to a different conclusion. I felt that for the following couple of weeks leading up to [the inauguration], it was probably more important rather than less important that I was here. …To walk away when the most important time was coming up, and at a time where tensions had gone through the roof, I just didn’t feel like that was my duty. My duty was to be here.”

Liddell described the mood among White House staff in the days leading up to the inauguration.

Liddell: “We’re down to a core staff now, a skeleton staff. I think everyone’s focused on [the inauguration]. …The relationship with the Biden transition team has been as good as it could possibly be. It’s been challenging at times, particularly during the last couple of weeks, but most of my interactions over the last few days have been about how we land the plane as well as we possibly 12:00 p.m. [on Inauguration Day]. Those of us that are left here are really focused on that.”

Liddell reflected on his time leading the Trump transition effort.

Liddell: “This has personally been the toughest assignment of my life. None of us want to go through what we went through during the last few weeks again. …But maybe I can finish on a slightly more positive note. In the last few weeks, we’ve thrown just about every possible bad scenario that you can think of at the country. And I believe we will have a successful and peaceful transition tomorrow. The institutions of this government have held. …At 12:00 tomorrow, President-elect Biden will become President Biden. The incoming transition team will be here, set up, ready to go. I think we’ve covered every possible scenario and I think this will be a successful transition. So in the most difficult circumstances that are humanly possible, the institution of the U.S. government, and the transition associated with it, will be successful.”

This week’s episode of Transition Lab features Yohannes Abraham, executive director of the Biden-Harris transition. He previously worked on Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign and held several positions in the Obama White House, including senior advisor to the National Economic Council and deputy assistant to the president for the Office of Public Engagement and International Affairs. Later, he helped direct Obama’s 2012 campaign and served as chief operating officer for the newly established Obama Foundation.

In this episode, host David Marchick spoke with Abraham about leading the Biden-Harris team, the lessons he has learned from previous transitions, and how the country’s health and economic crises have affected his work.

[tunein id=”t159975749″]

By Max Stier, President and CEO of the Partnership for Public Service

In the aftershock of the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Wednesday, I wanted to share my reflections as our country continues to collectively process what transpired.

Like so many of you, I was appalled and sickened by the violence that erupted in the hallowed chambers of our Capitol. The attack on our democracy was a moment of heartbreak and a loss of faith in some of our elected leaders whose rhetoric led to the actions that were laid bare on Wednesday.

We have experienced many contentious elections in the 230-year history of our great nation. Yet, there has always been a peaceful and orderly transition of power, and this has been a hallmark of our democracy and vital to the safety of the public. To see it under threat is shocking and disheartening.

Yet, the peaceful transfer of power is not in itself enough to sustain our democracy. There also must be an effective transfer of power, which is now threatened.

Under ordinary circumstances, the effective transfer of power is incredibly difficult given the scale, complexity and shortness of time to prepare to govern, and these are by no means ordinary times. The Trump administration has been slow to cooperate, and the pandemic has added urgency to what is at stake and made the transition process more difficult given that much of the work must be done virtually.

The most important element of a transition is getting a new leadership team in place quickly, up-to-speed and working well together with the professional career workforce. President-elect’s Joe Biden’s team has done an exceptional job in preparing to govern, but the hardest work is just beginning.

The Senate has a critical role to play in quickly reviewing and voting on the new president’s nominees. According to research by the Partnership’s Center for Presidential Transition, presidential appointees requiring Senate confirmation face a process that is longer, harder, more public and more complex than their predecessors faced 40 years ago. The Senate must move swiftly and across party lines to confirm qualified appointees.

Getting this right is essential to solving our country’s biggest problems and rebuilding trust with the people our government serves. To do so will require reimagining the responsibilities of our government leaders. The core expectation must be for our leaders to be motivated and held accountable for serving the public interest rather than their own private or partisan interests.

During his 1863 Gettysburg Address, Abraham Lincoln made an impassioned plea for the country to heal from the wounds of the Civil War, asserting that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Our government, wholly owned by the people of this nation, can achieve great things. Our government defeated fascism, made factories safe places to work, eradicated polio and measles, provided pensions and healthcare to seniors, cleaned up our air and water, put astronauts on the moon, invented the Internet, and is now on the frontlines battling the COVID-19 pandemic.

The work of strengthening our democracy and repairing and rebuilding our institutions does not belong to one party or person. It requires each of us, including our elected leaders and political appointees, to play a critical role. Recognizing that and acting on it is part of what it means to be an American.

This piece was originally published on the Partnership for Public Service’s blog, We the Partnership.

By Bishop Garrison

This post is part of the Partnership’s Ready to Serve series. Ready to Serve is a centralized resource for people who aspire to serve in a presidential administration as a political appointee.

The chance to work in a presidential administration is an experience like no other, offering a unique opportunity to serve the nation and its citizens.

From my experience in various positions during President Barack Obama’s administration, I gained insights into issues candidates should consider when deciding whether to pursue a political appointment. The following advice will help you decide if a presidential appointment is right for you.

Before accepting a position, ask yourself about your motivation to join and if now is the right time to serve.

An offer to serve your country can be one of the highest honors of an individual’s professional life. Securing such a position is a competitive process and can lead to more prestigious jobs in the future. However, there is a thin line between a true desire to serve and an interest in furthering your career. If you are offered a political appointment, make sure you are accepting it for the right reasons. Ensure it is the right fit for your own interests and career. You will need to give your all every day, so make sure it’s a position that can make you happy.

If you accept a position, seek out new challenges that may not have been part of your original career goals.

A presidential appointment will lead to opportunities for professional development and for learning new skills. When circumstances allow, seek out new challenges, especially ones you did not anticipate. Many of the best opportunities to grow will come from tasks outside of your primary responsibilities. It may be supporting a project in another directorate serving as an extra pair of hands or joining optional professional development sessions. There is no one true path to success, and exploring less obvious avenues will provide unexpected, yet rewarding experiences.

Prepare for difficult times and view them as opportunities to learn and grow.

Former Secretary of State Colin Powell once said, “All work is admirable.” While Powell’s statement rings true, not every part of your job will be like the inspiring television episodes of The West Wing or Madam Secretary. There will be times of exhaustion and frustration, but they can be buoyed by the opportunity to accomplish important work and rebuild faith in our government. Meet with your career colleagues and learn from them. They can provide a wealth of knowledge based on their varied experiences. They understand these institutions intimately and what it will take to engage the public through smart, thoughtful policy and action.

The Bottom Line

Before accepting a political appointment, make sure you consider all potential factors that may affect you, such as personal motivation, work-life balance, financial concerns and the demands of the position. Many appointees do not think about these questions until it is too late, and they should play a role in in whether to accept a presidential appointment.

At the end of the day, however, serving in a presidential administration is an honor and a unique opportunity to make a difference. Whatever you choose, ensure it is the right decision for you.

Bishop Garrison served in various national security positions in the Obama administration and as deputy foreign policy adviser for the 2016 Hillary Clinton campaign. He is currently director of national security outreach for Human Rights Watch.

Filling key health-related positions was not a priority during recent presidential transitions. By their 100th day in office, only 28% were filled under Trump and 35% under Obama.

By Christina Condreay

As medical professionals and essential workers begin to receive the coronavirus vaccine, the nation enters a new phase of the pandemic. Yet even with this positive development, the country faces thousands of deaths from the virus each day and will likely be dealing with the pandemic for months to come. With the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden only days away, the new administration will need key health officials in place quickly to coordinate the government’s response and assure continuity during the change in leadership.

Biden’s plan for a COVID-19 response includes providing 100 million vaccines in 100 days and reopening schools safely by May. To achieve these goals, he must have personnel in key decision-making positions. Recent history, however, shows that under the last two presidents, most health-focused jobs were not among the earliest filled. In fact, under Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama, only about one-third of leadership positions responsible for coordinating health efforts were confirmed by the Senate within 100 days of taking office.

To study the priority given to these roles, the Partnership for Public Service’s Center for Presidential Transition identified 50 Senate-confirmed positions relating to public health and emergency response. The list is comprised of positions held by individuals on the current coronavirus task force, health-related nominees already announced by Biden and the positions of those who participated in the 2016 transition pandemic tabletop exercises. Additionally, the Center examined job descriptions for more than 400 positions across 22 agencies. The final list of 50 includes agency heads and Cabinet department secretaries, as well as assistant and undersecretaries responsible for less visible but important agency subcomponents.

Pandemic response positions during the Trump administration

Of these 50 key positions, only 14 were filled during the first 100 days of the Trump administration (28%). When the pandemic began in early 2020 – and Trump had been in office for three years – only 28 of these 50 positions or 56% were filled with a Senate-confirmed official. Even though the Senate confirmed these officials, significant turnover occurred during Trump’s first three years. Between Inauguration Day and March 1, 2020, 20 Senate-confirmed officials in pandemic response positions had resigned.

The lack of Senate-confirmed officials was due in part to Trump’s slow pace of nominations. During Trump’s first year in office, he submitted nominees for just 27 of the selected positions. In his second year, Trump submitted nominations for only 11 more. Another cause of the delays was the length of time it took the Senate to vote on nominations.

All told, 42 of the 50 health-related positions were filled at some point during the Trump presidency, even if not by the start of the pandemic. On average, the Senate took 99 days to confirm those nominations.

Pandemic response positions during the Obama administration

The Obama administration filled a few more of these health-related jobs early in its first year, but only by a small margin. During the first 100 days, 35% of these positions had a Senate-confirmed official, including four holdovers from President George W. Bush’s administration. There was a notable difference, however, in staffing these positions during Obama’s second year. By the end of Obama’s second year in office, the administration had sent nominations for 39 of the 50 positions to the Senate.

Due to key holdovers from the Bush administration and five recess appointments, a permanent official served in 49 of the health-related positions by the end of Obama’s third year. The Trump administration added a Senate-confirmed position, the director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, which is included in our list. On average, the Senate took 71 days to confirm officials for those positions during the Obama administration.

Conclusion

An effective strategy to fight the pandemic requires a smooth transition of power and continuity in leadership. Although many health-related positions were not filled quickly during the last two administrations, the Senate and Biden administration have a joint obligation to expeditiously nominate and confirm officials for these critical roles to deal with the current crisis.

Ted Kaufman and President-elect Joe Biden go way back. Kaufman helped organize Biden’s first Senate office in 1972 and served as his chief of staff for nearly two decades. Kaufman left the Senate in 1994, but later returned to fill his old boss’s seat after Biden became Barack Obama’s vice president in 2009. More recently, Kaufman helped pass two laws, one in 2010 and another in 2015, that improved the presidential transition process. He currently co-chairs the Biden-Harris transition team.

In this episode of Transition Lab—the first to focus on the Biden transition to power—host David Marchick asks Kaufman to discuss Biden’s transition planning process. Marchick also discusses with Kaufman how he became a leading transition expert, why the Biden-Harris transition will serve as a model for future transition teams and how he has approached the unique challenges of the 2020 transition cycle.

[tunein id=”t159532888″]

Read the highlights:

Kaufman recalled Joe Biden asking him to run the transition:

Kaufman: “It was in the spring. We had been talking … about the campaign. I think maybe I mentioned the transition in passing, but [did not say] anything about if we ought to start or whatnot. I don’t think there’s ever been a transition that started in the early spring. And then he called me, and he said, ‘You know, I’ve been thinking about this transition and I think we ought to get started right now.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ll tell you what … if you go to one of these Partnership for Public Services get-togethers, you learn one thing: You can’t start too early.’ And so, I said to him that I would start it. …It was really one of the smartest things we [did].”

Kaufman described the relationship between the campaign and transition teams.

Kaufman: “Until Election Day, the campaign [was] by far the most important part of the Biden effort. We talked with campaign [staff] and cleared everything we did all the time. …The transition is not about making policy. It’s about getting to the bottom of what a President Biden would want to do when he became president. …We got from the campaign all of the policy statements he made, and we collected them into what we called a campaign promises book. Then, the transition took the book and sliced it and diced so that people [responsible for] each agency knew what the Biden policies were for that specific agency.”

Kaufman explained why the transition team embraced the motto, “Whatever happens in the transition, stays in the transition.”

Kaufman: “We knew that there would be incredible interest in what was happening in all parts of the transition, especially who was going to get positions in the administration. It’s like the greatest parlor game or rabbit hunt in Washington during the period that the transition is ongoing. Who’s going to get a job? When are they going to get them? Who’s going to get what? Who’s going to be in line? Those types of things. Everyone took [the transition team’s] responsibility seriously. [As a result], there were very few accurate reports of what was happening during the transition.”

Kaufman described building a diverse transition team.

Kaufman: “President-elect Biden’s most important commitment was having an administration that reflected America. And I must tell you, because of the incredible number of highly qualified people interested in serving the transition, this was no problem. And we turned out to have a transition that genuinely mirrored America in just about every way”

Kaufman reflected on planning a virtual transition.

Kaufman: “When we started [the transition], we were just about a month into the period when businesses [and] schools had been shut down, and we had no idea how long that would last. We also were just learning to be efficient on Zoom and other platforms. We realized we needed to plan for a virtual transition, and we did. It increased the degree of difficulty considerably. But thanks to good planning, coordination, and communication, [the transition] has been seamless.”

Kaufman discussed the impact of his transition legislation:

Kaufman: “In 2010 … the Senate passed my bill, Senate bill 3196. It moved up the date that the transition teams get access to office space, computers, phones and funding from the government. Prior to the legislation, support from the General Services Administration only kicked in after the election. …I said before about how difficult it is to have a transition in the most complex organization in the history of the world. You’re supposed to basically do it in 70 days. What my bill did was increase it from 70 to more like 140 days. Instead of getting the financing help after the election, you got the financing help after the convention.”

Kaufman reflected on Biden’s Cabinet nominees:

Kaufman: “I think these nominees [are] highly qualified. They’re experienced. And they’re breaking barriers. …The first person of color to run the Defense Department, the first female to be the Director of National Intelligence, the first gay Cabinet secretary. It’s about a half a dozen different [minority groups] that were not represented [before].”

Kaufman compared the challenges of the 2020 transition with those of 2008:

Kaufman: “I thought we [saw] the most difficult transition because of the Great Recession, but it’s nothing like this. I mean, no other transition has ever taken place with these set of challenges: a pandemic, a recession, a racial justice crisis, an unpredictable president and political polarization. I realized that we had to build off the best of what previous transitions had done—and do much more—to ensure that Vice President Biden would be ready to govern on Inauguration Day.”

This blog was updated on January 13, 2021.

First President from First State Produces Many Firsts

By Isabella Epstein and Paul Hitlin

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised to form a diverse administration that would “look like America.” His choices for leadership positions would make his Cabinet the most diverse in the country’s history.

President-elect Biden has announced 24 people to fill Cabinet-level positions as determined by The Washington Post. Of those, 17 are identified as women, people of color or LGBTQ. He has also announced 11 nominees to other positions requiring Senate approval, many of whom will be the first women or people of color to hold their posts. These nominations include the historic election of Kamala Harris as the first woman, African American and South Asian American vice president. Pending Senate confirmation, the Biden team will include among its leaders:

- Wally Adeyamo, the most senior person of color ever to serve at the Department of Treasury.

- General Lloyd Austin, the first African American secretary of Defense.

- Xavier Becerra, the first Latino secretary of Health and Human Services.

- Pete Buttigieg, the first openly gay person confirmed to lead a Cabinet department as secretary of Transportation.

- Marcia Fudge, the first woman secretary of Housing and Urban Development in over 40 years and the second African American woman to lead the department.

- Deb Haaland, the first Native American to lead a Cabinet department as secretary of the Interior.

- Kathleen Hicks, the first woman to serve as deputy secretary of defense.

- Vanita Gupta, the first woman of color to serve as associate attorney general.

- Alejandro Mayorkas, the first immigrant and Latino secretary of Homeland Security.

- Michael S. Regan, the first African American man to lead the Environmental Protection Agency.

- Cecilia Rouse, the first woman and first African American Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers.

- Katherine Tai, the first Asian American and first woman of color to serve as U.S. Trade Representative.

- Neera Tanden, the first woman of color and first South Asian American to serve as director of the Office of Management and Budget.

- Janet Yellen, the first woman to serve as secretary of the Treasury.

Undoubtedly, the racial, gender and sexual identities of the Biden team are only some measures of diversity. Many stakeholders are looking to different or specific individual metrics to assess the diversity of Biden’s cabinet. And, despite the symbolism of his appointments, the federal government has a long path ahead in its pursuit of comprehensive diversity, equity and inclusion at every level. For example, only 22% of those in the Senior Executive Service – the elite corps of career civil servants responsible for leading the federal workforce – identify as people of color, compared with about 40% of the U.S. population.

Recognizing this issue, presidents before Trump increasingly prioritized diversity in their initial Cabinets. A New York Times study compares initial Cabinet appointments:

- 12 of President Bill Clinton’s initial 22 picks identified as women or people of color, the first Cabinet comprised of majority women and minority officials.

- 9 of President George W. Bush’s initial 20 picks identified as women or people of color.

- 14 of President Barack Obama’s initial 22 picks identified as women or people of color.

- 6 of President Donald Trump’s initial 24 picks identified as women or people of color.

Beyond creating a government that represents the country’s population, diversity enhances the decision-making process. As a Harvard Business Review article suggests, diversity precludes groupthink, encourages debate and improves strategic thinking. Thus, differences in background, opinion and perspective can produce better policy outcomes. As the Partnership for Public Service’s DEI statement explains, “The work of diversity, equity and inclusion is a challenging, continuous journey that demands humility, empathy and growth.”

Considering these factors, President-elect Biden’s Cabinet picks are historic.