By Carlos Galina

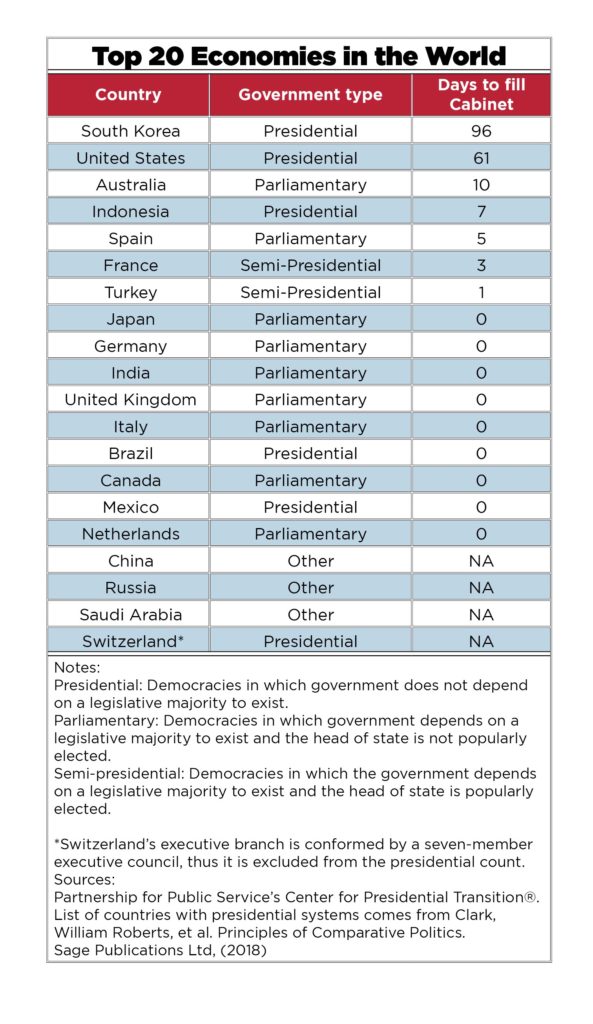

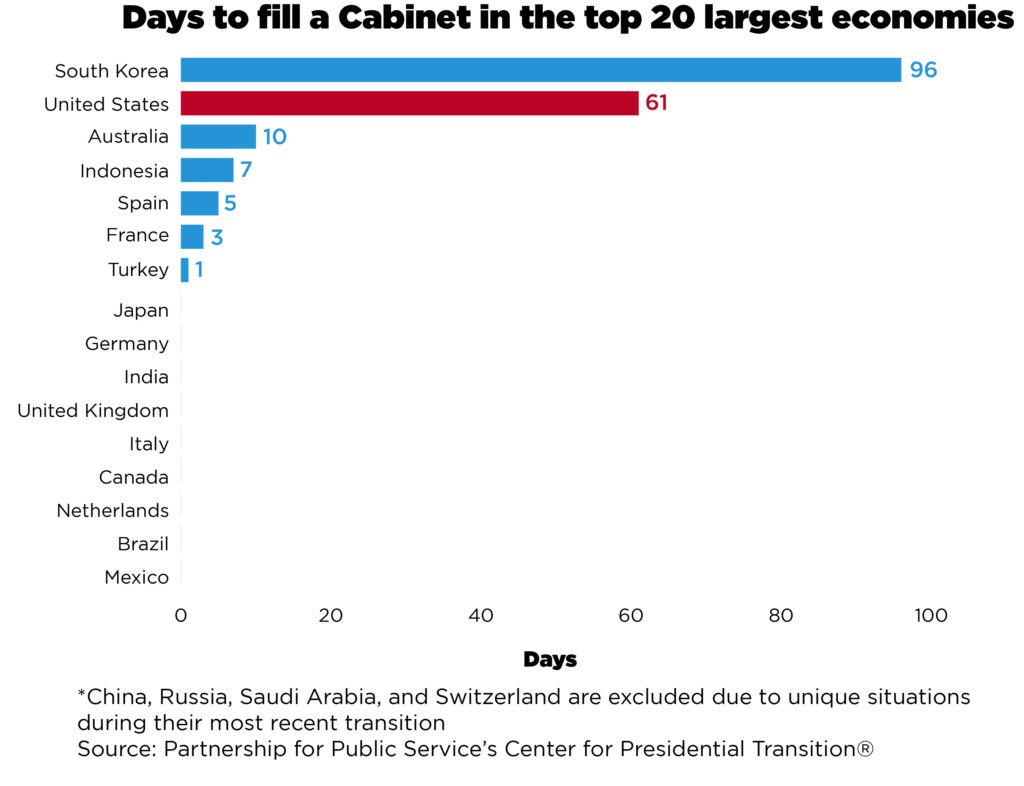

With the confirmation of Marty Walsh on March 22 to be secretary of Labor, the Senate approved all of President Joe Biden’s 15 Cabinet statutory nominations in 61 days. How does the U.S. appointment process compare with other countries?

The answer is that the U.S. takes far longer to confirm its executive Cabinet than most other countries.

Among the 20 countries with the highest gross domestic product, the U.S. was the second slowest during the most recent transitions to a new head of state.

Besides having more positions requiring political appointments, the slow confirmation process is largely explained by the fact that the U.S. has a presidential form of government. The Constitution defines this form of governing as having an executive who serves as the head of the government and is separate from the legislative branch. Only six of the 20 largest economies have presidential systems. Many others have forms of government which give the executive more control over the selection of their Cabinet. For example, Canada, Germany and the United Kingdom typically have a prepared list of Cabinet appointees ready for consideration on the day of the executive’s inauguration.

Filling a Cabinet is critical for any new administration to begin governing. Cabinets comprise the secretaries or ministers heading various departments, and executives benefit from having key leadership positions filled quickly in order to execute their agendas. Delays in getting essential staff in place can leave national security planning gaps while slowing policy implementation and personnel decisions.

In the U.S., the length of the confirmation process has varied in recent years. While the Senate took 61 days to confirm Biden’s Cabinet, Presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama had all of their Cabinet secretaries confirmed in 97 and 98 days, respectively. President George W. Bush’s full Cabinet was confirmed in 12 days and President Bill Clinton’s in 50.

The confirmation of Cabinet officials is an important part of our system of checks and balances, and gives the legislative branch oversight power on parts of the executive branch. However, even when comparing the length of the American process with other countries that have a similar form of government – most of which are much smaller – the American confirmation process is among the longest.

Of the 30 countries with the highest GDP and presidential systems, only three took longer than the U.S. to fill their Cabinet in the most recent transitions to a new head of state: Nigeria (166 days), Liberia (108) and South Korea (96).

According to each country’s constitution, only six of those 30 countries with presidential systems require Cabinet confirmations by a national legislature. By contrast, other presidential systems provide presidents with full responsibility to select, appoint and have their executive team ready to govern on their first day in office. Countries such as Brazil, Chile and 14 others have Cabinets ready to serve on the day of the executive’s inauguration. Some of those countries give their legislatures confirmation authority for positions beyond the executive team, but unlike the U.S., they give the president full power to place most of their top officials.

According to David Lewis, a political scientist at Vanderbilt University, the U.S. has far more political appointees than any other developed democracy. Even though the U.S. confirmation system strengthens the system of checks and balances, delays in confirming Cabinet secretaries can influence staffing and the incoming administration’s capacity to govern. Congress and the White House should consider ways to make the entire confirmation process more efficient.

While the Constitution created a presidential system along with the Senate’s advice and consent role, and while legislative oversight of the president’s nominees is a critical democratic principle, today’s process is longer than almost anywhere else in the world. Steps should be taken to speed up the process so that incoming presidents have key leaders in place on or shortly after Inauguration Day to address the nation’s challenges.

The Center for Presidential Transition would like to thank Frieda Arenos of the National Democratic Institute for offering feedback for this report.

Editorial credit: Andrea Izzotti / Shutterstock.com

By Paul Hitlin

The withdrawal of Neera Tanden’s nomination to be the director of the Office of Management and Budget has left President Joe Biden with a challenge faced by the previous five presidents – an unsuccessful Cabinet-level nomination early in their tenure.

Biden becomes the sixth president in a row who has notched at least one unsuccessful Cabinet-level nomination by the end of their first two months in office. Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Donald Trump each had one, while President Barack Obama had three.

The large majority of early Cabinet nominations are confirmed. The three presidents preceding Biden – George W. Bush, Obama and Trump – announced 59 nominations combined for Cabinet-level positions within two months of taking office. Of those, 54 were approved by the Senate and five were unsuccessful.

The few who did not succeed received significant attention. For example, Trump’s initial secretary of Labor nominee Andrew Puzder was withdrawn before a Senate hearing due to concerns over financial issues and personal conduct. Tom Daschle, Obama’s first pick for secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, withdrew before a hearing due to a widely-covered tax controversy. The controversy over the hiring of undocumented immigrants for Clinton’s first attorney general nominee, Zoë Baird, was so widely covered it earned the moniker “Nannygate.” Eight years later, a similar controversy derailed George W. Bush’s first nominee for Labor secretary, Linda Chavez.

As with Tanden, most unsuccessful nominees are withdrawn prior to a Senate vote when it becomes apparent there is not enough support for confirmation. Administrations typically anticipate a candidate cannot win in the Senate and withdraw the nomination before a failed vote takes place. In fact, only one Cabinet nominee has been rejected in a Senate floor vote in the last 60 years – George H. W. Bush’s nominee for secretary of Defense, John Tower, in 1989.

In some instances, presidents have withdrawn nominations before the paperwork is officially submitted to the Senate. Of the five early Cabinet nominees named by George W. Bush, Obama and Trump who did not get confirmed, three were never actually received by the Senate.

As in the case of Tanden, failed nominations represent a temporary setback for the administration, unleash political jockeying among those promoting replacement candidates, and leave a department or agency without a Senate-confirmed leader. In this case, the Biden administration will have to proceed with its preparation of a new budget and be delayed in crafting a new management agenda without the head of OMB in place.

While this process creates complications for a president, it is one envisioned by the framers when they gave the Senate its advise and consent role on presidential nominations. Like other presidents, Biden will choose a new nominee, reach accommodation with the Senate and seek to make up for lost time.

By Drew Flanagan

Slightly more than one month into his administration, just over half of President Biden’s 15 Cabinet secretary nominees have been confirmed. At a comparable time, the previous four presidents had 84% of their Cabinet picks confirmed. In fact, President George W. Bush had his entire Cabinet in place and President Bill Clinton had all but one position filled.

The pace of confirming Cabinet secretaries historically influences the staffing of other leadership positions such as deputy secretaries and undersecretaries. Recent presidents have rarely nominated anyone to fill sub-Cabinet positions until the agency head has been confirmed. Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump collectively announced 274 sub-Cabinet nominations by the end of their first 100 days in office. Of these, only 18 or just 7% were sent to the Senate before the confirmation of their agency head.

This practice reflects deference toward the Cabinet secretaries and provides them with an opportunity to participate in the selection of officials who would work with them.

However, the current slow pace of confirmations has forced the Biden administration to operate differently. The White House has already submitted 22 sub-Cabinet positions to the Senate, 19 of which were sent before the Cabinet secretaries were confirmed (86%). Biden’s decision to take a fresh approach is likely the result of his transition team anticipating Cabinet confirmations taking longer than usual.

It is worth noting that Senate action in 2021 has been hindered by various highly unique events, including the Senate run-off election in Georgia, impeachment proceedings and negotiations over the Senate power-sharing agreement. Even so, the negative impacts of these delays remain significant, extending far beyond sub-Cabinet nominations. Without confirmed Cabinet secretaries, important decisions get postponed and government employees face uncertainty – problems that are magnified now as the country deals with the pandemic, an economic crisis and many other domestic and foreign policy challenges.

Overall, the Biden administration is ahead of the pace of nominations set by previous presidents. Biden has submitted 55 nominations to the Senate, 15% more than any of the previous five presidents at a comparable moment. Despite the high pace of personnel announcements, the Senate has confirmed just 11 of the 55 submitted nominees, including eight of 15 Cabinet secretaries.

Filling key administration jobs has taken on added significance due to the vulnerabilities posed by the crises facing our country. The sooner Biden’s Cabinet secretaries and other nominees are confirmed, the sooner they can get to work.

This blog was updated on January 13, 2021.

First President from First State Produces Many Firsts

By Isabella Epstein and Paul Hitlin

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised to form a diverse administration that would “look like America.” His choices for leadership positions would make his Cabinet the most diverse in the country’s history.

President-elect Biden has announced 24 people to fill Cabinet-level positions as determined by The Washington Post. Of those, 17 are identified as women, people of color or LGBTQ. He has also announced 11 nominees to other positions requiring Senate approval, many of whom will be the first women or people of color to hold their posts. These nominations include the historic election of Kamala Harris as the first woman, African American and South Asian American vice president. Pending Senate confirmation, the Biden team will include among its leaders:

- Wally Adeyamo, the most senior person of color ever to serve at the Department of Treasury.

- General Lloyd Austin, the first African American secretary of Defense.

- Xavier Becerra, the first Latino secretary of Health and Human Services.

- Pete Buttigieg, the first openly gay person confirmed to lead a Cabinet department as secretary of Transportation.

- Marcia Fudge, the first woman secretary of Housing and Urban Development in over 40 years and the second African American woman to lead the department.

- Deb Haaland, the first Native American to lead a Cabinet department as secretary of the Interior.

- Kathleen Hicks, the first woman to serve as deputy secretary of defense.

- Vanita Gupta, the first woman of color to serve as associate attorney general.

- Alejandro Mayorkas, the first immigrant and Latino secretary of Homeland Security.

- Michael S. Regan, the first African American man to lead the Environmental Protection Agency.

- Cecilia Rouse, the first woman and first African American Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers.

- Katherine Tai, the first Asian American and first woman of color to serve as U.S. Trade Representative.

- Neera Tanden, the first woman of color and first South Asian American to serve as director of the Office of Management and Budget.

- Janet Yellen, the first woman to serve as secretary of the Treasury.

Undoubtedly, the racial, gender and sexual identities of the Biden team are only some measures of diversity. Many stakeholders are looking to different or specific individual metrics to assess the diversity of Biden’s cabinet. And, despite the symbolism of his appointments, the federal government has a long path ahead in its pursuit of comprehensive diversity, equity and inclusion at every level. For example, only 22% of those in the Senior Executive Service – the elite corps of career civil servants responsible for leading the federal workforce – identify as people of color, compared with about 40% of the U.S. population.

Recognizing this issue, presidents before Trump increasingly prioritized diversity in their initial Cabinets. A New York Times study compares initial Cabinet appointments:

- 12 of President Bill Clinton’s initial 22 picks identified as women or people of color, the first Cabinet comprised of majority women and minority officials.

- 9 of President George W. Bush’s initial 20 picks identified as women or people of color.

- 14 of President Barack Obama’s initial 22 picks identified as women or people of color.

- 6 of President Donald Trump’s initial 24 picks identified as women or people of color.

Beyond creating a government that represents the country’s population, diversity enhances the decision-making process. As a Harvard Business Review article suggests, diversity precludes groupthink, encourages debate and improves strategic thinking. Thus, differences in background, opinion and perspective can produce better policy outcomes. As the Partnership for Public Service’s DEI statement explains, “The work of diversity, equity and inclusion is a challenging, continuous journey that demands humility, empathy and growth.”

Considering these factors, President-elect Biden’s Cabinet picks are historic.

Michael Froman has had an extraordinary career. After serving in the Department of the Treasury under President Clinton, he became the head of personnel for the 2008 Obama-Biden transition team and later served as a White House deputy national security advisor and as the U.S. Trade Representative. In this episode of Transition Lab, host David Marchick asks Froman for an inside look at the world of vetting, selecting and appointing key presidential personnel. They discuss how Froman got involved in transition planning, the lessons his experience holds for future administrations and President Obama’s personnel strategy.

[tunein id=”t157772631″]

Read the highlights:

Marchick asked Froman how he got involved in the 2008 Obama-Biden transition.

Froman: “I had known President Obama from [Harvard] Law School. …And when he became senator, a group of us whom he had known either from law school or other places had helped … hire some of his initial staff. …When he decided to run for president, I offered to help him with the transition, in part because I wasn’t planning on going into government and thought that I could make a contribution by helping him with the personnel process.”

Marchick asked how potential nominees for President Obama’s Cabinet were selected.

Froman: “We’d look at the national security team, the economic team, the domestic policy team, the environment team and come up with lists of names of people who could fill potentially multiple positions. The approach was more to look at teams rather than individual positions. It wasn’t so much having five candidates for one job, but more of having 15 candidates for a handful of jobs. …It was more going out and looking for as many qualified, diverse candidates as possible so that the president would have maximum opportunity to … [put] together the Cabinet that he wanted.”

Marchick asked which personnel decisions took priority.

Froman: “His first decision was not a Cabinet position. It was the position of White House chief of staff and he chose Rahm Emanuel, which also then helped further the process because Rahm was very focused on both the Cabinet and the White House staff. …Because of the global financial crisis, there was a particular momentum for getting decisions around the economic team.”

Marchick asked whether the campaign staff jockeyed for jobs in the administration after the 2008 election.

Froman: “There certainly was an element of that, but people were actually engaged in pretty good behavior. …People [on the] campaign … of course had hoped to get into the administration, but there weren’t a lot of sharp elbows … [President Obama] had not been in Washington for years and years, and he didn’t have a list of a thousand people that he needed jobs for. …He was really quite open to meeting whoever was the the best candidate for the job.”

Marchick asked how successful candidates approached the vetting process for a position in the Obama administration.

Froman: “People who came in and said, ‘I am the greatest expert in this area, I have served the three of the last Democratic administrations and I am clearly the most qualified person for this position. Where do I fill out my employment forms?’ didn’t tend to [do] very well. …The more successful approach was to make clear that you were low maintenance; that you wanted to serve; that there were a variety of positions that you could envisage yourself doing; that you were not insistent on necessarily being the top person in any agency; [and] that you were willing to play whatever role the president-elect felt was appropriate.”

Marchick asked what lessons future administrations should take from the slower rate at which President Obama filled Senate-confirmed positions after his first year in office.

Froman: “One of the lessons of that is that it’s better to have somebody who is doing personnel during the transition into at least the first year of the administration—maybe into the first two years of the administration. Having that continuity would have been better in retrospect.”

Marchick asked why President Obama wanted to build a diverse Cabinet.

Froman: “The president had made clear he wanted an administration that looked like America, and we were committed to having a diverse Cabinet and sub-Cabinet … So one of our areas of focus was ensuring that the slates [of potential nominees] were as diverse as possible—whether it was racial diversity, ethnic diversity, gender diversity, among other attributes.”

Marchick asked Froman to discuss the advice he would offer presidential transition personnel planners.

Froman: “When you’re picking a team of Cabinet and sub-Cabinet officials, one should be thinking about who [we are] putting in the pipeline who could succeed the Cabinet, and how do we make sure that they get the support and the training … to fill out their attributes so that they could step up be Cabinet officers as well. The one thing we don’t do terribly well in the federal government compared to some of other organizations, including in the private sector, is [think] about succession planning [and] how to prepare people to step up into the next position.