Almost half of key national security positions requiring Senate confirmation were vacant on 9/11/2001

By Alex Tippett

A transition to a new presidential administration is a unique moment of vulnerability for our country. As President-elect Joe Biden selects his full national security team and the Senate prepares to consider presidential appointments, the experiences of previous transitions serve as cautionary tale for why slow nominations and lengthy confirmation processes can leave the nation vulnerable.

The most prominent example of how a prolonged confirmation process can undermine national security is the terrorist attacks of the Sept. 11, 2001, which occurred about eight months into President George W. Bush’s first year in office. At that time, many national security positions were vacant due in part to the shortened transition period after the contested 2000 election and the challenges associated with getting officials into Senate-confirmed positions.

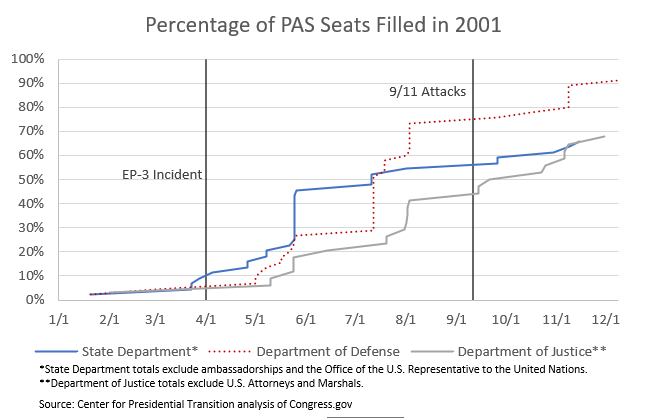

At the time of the attacks, only 57% of the 123 top Senate-confirmed positions were filled at the Pentagon, Department of Justice and Department of State combined excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys. Of those officials who were in place, slightly less than half (45%) had been confirmed within the previous two months.

The bipartisan 9/11 Commission, which reviewed the causes of the attacks and its consequences, focused on the impact of the slow confirmation process. The commission suggested that delays could undermine the country’s safety, arguing that because “a catastrophic attack could occur with little or no notice, we should minimize as much as possible the disruption of national security policymaking during the change of administrations by accelerating the process for national security appointments.”

While Congress implemented a number of the commission’s recommendations, the nomination process continues to be a liability and underlines the importance of moving swiftly to confirm qualified nominees.

Confirming the Bush National Security Team

Most of Bush’s leadership at the Department of Defense took months to get into place. While Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was confirmed on Jan. 20, 2001 and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, was confirmed in late February and no other member of the DOD’s leadership team was confirmed until May.

It was during this period that the Bush administration faced its first major national security test. On April 1, 2001, a Navy surveillance plane collided with a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea. The Chinese pilot was killed in the collision and the American crew was taken into captivity. Over the next 11 days, a tense standoff ensued. While the crisis was eventually brought to a peaceful close, Wolfowitz and Rumsfeld were the only Senate-confirmed members of Bush’s DOD team, with the third and fourth ranking appointees confirmed on May 1, 2001—a full month after the incident began.

By the time of the 9/11 attacks, the Senate had confirmed a total of 33 DOD officials. Two-thirds of those officials had been on the job for less than two months. According to the 2000 Plum Book, there were 45 positions at DOD requiring Senate confirmation, leaving 12 important jobs empty on 9/11.

In an interview with the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, Stephen Hadley, Bush’s deputy national security advisor, suggested the slow pace of nominations undermined the administration’s ability to develop a response to the threat posed by the al-Qaeda terrorist group responsible for 9/11. “When people say, ‘Well, you had nine months to get an alternative strategy on al-Qaeda,’ no, you didn’t. Once people got up and got in their jobs you had about four months.”

Empty seats and a slow nomination process also hurt other parts of the Bush administration. Michael Chertoff, who served as head of the Department of Justice’s criminal division on 9/11, recalled, “We were shorthanded in terms of senior people….we essentially had to do double and triple-duty to pick up some of the responsibilities that would have been taken by others who were confirmed.”

Following a bitter five-week struggle, John Ashcroft was confirmed as attorney general on Feb. 1, 2001. His deputy, Larry Thompson, was confirmed on May 10, along with Assistant Attorney for Legislative Affairs Daniel Bryant.

Excluding U.S. marshals and attorneys, DOJ had 34 Senate-confirmedpositions in 2000. But Just 41% of those jobs were filled on 9/11. Half of those 14 officials—including then FBI Director Robert Mueller–were on the job less than two months before the attacks.

Bush’s State Department, supported by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, moved faster than other committees in the early days of the administration, but then slowed its pace. Before June, the State Department filled 20 of 44 Senate-confirmed positions, excluding ambassadorships. On 9/11, just 24, or 55%, of the 44 positions at the State Department were filled.

Conclusion

In light of these delays, the 9/11 commission recommended that, “A president-elect should submit the nominations of the entire new national security team, through the level of undersecretary of Cabinet departments, not later than January 20. The Senate, in return, should adopt special rules requiring hearings and votes to confirm or reject national security nominees within 30 days of their submission.”

Both the Senate and the Biden team should work to meet this standard. And while the Senate should carefully scrutinize every nominee, it also should recognize that unnecessary delays could undermine the ability of the new administration to respond to the threats we currently face and those that are unexpected.