Almost half of key national security positions requiring Senate confirmation were vacant on 9/11/2001

By Alex Tippett

A transition to a new presidential administration is a unique moment of vulnerability for our country. As President-elect Joe Biden selects his full national security team and the Senate prepares to consider presidential appointments, the experiences of previous transitions serve as cautionary tale for why slow nominations and lengthy confirmation processes can leave the nation vulnerable.

The most prominent example of how a prolonged confirmation process can undermine national security is the terrorist attacks of the Sept. 11, 2001, which occurred about eight months into President George W. Bush’s first year in office. At that time, many national security positions were vacant due in part to the shortened transition period after the contested 2000 election and the challenges associated with getting officials into Senate-confirmed positions.

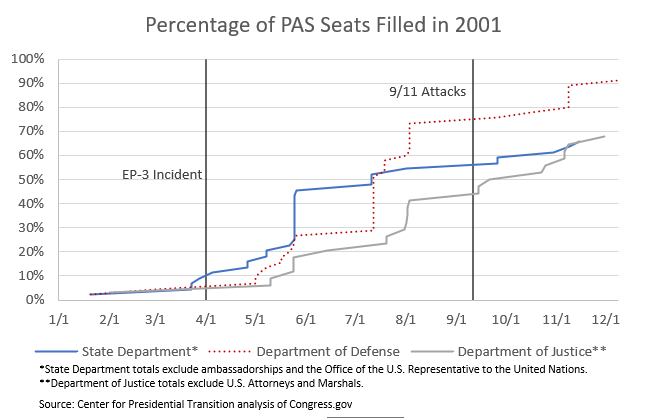

At the time of the attacks, only 57% of the 123 top Senate-confirmed positions were filled at the Pentagon, Department of Justice and Department of State combined excluding ambassadors, U.S. marshals and attorneys. Of those officials who were in place, slightly less than half (45%) had been confirmed within the previous two months.

The bipartisan 9/11 Commission, which reviewed the causes of the attacks and its consequences, focused on the impact of the slow confirmation process. The commission suggested that delays could undermine the country’s safety, arguing that because “a catastrophic attack could occur with little or no notice, we should minimize as much as possible the disruption of national security policymaking during the change of administrations by accelerating the process for national security appointments.”

While Congress implemented a number of the commission’s recommendations, the nomination process continues to be a liability and underlines the importance of moving swiftly to confirm qualified nominees.

Confirming the Bush National Security Team

Most of Bush’s leadership at the Department of Defense took months to get into place. While Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was confirmed on Jan. 20, 2001 and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, was confirmed in late February and no other member of the DOD’s leadership team was confirmed until May.

It was during this period that the Bush administration faced its first major national security test. On April 1, 2001, a Navy surveillance plane collided with a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea. The Chinese pilot was killed in the collision and the American crew was taken into captivity. Over the next 11 days, a tense standoff ensued. While the crisis was eventually brought to a peaceful close, Wolfowitz and Rumsfeld were the only Senate-confirmed members of Bush’s DOD team, with the third and fourth ranking appointees confirmed on May 1, 2001—a full month after the incident began.

By the time of the 9/11 attacks, the Senate had confirmed a total of 33 DOD officials. Two-thirds of those officials had been on the job for less than two months. According to the 2000 Plum Book, there were 45 positions at DOD requiring Senate confirmation, leaving 12 important jobs empty on 9/11.

In an interview with the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, Stephen Hadley, Bush’s deputy national security advisor, suggested the slow pace of nominations undermined the administration’s ability to develop a response to the threat posed by the al-Qaeda terrorist group responsible for 9/11. “When people say, ‘Well, you had nine months to get an alternative strategy on al-Qaeda,’ no, you didn’t. Once people got up and got in their jobs you had about four months.”

Empty seats and a slow nomination process also hurt other parts of the Bush administration. Michael Chertoff, who served as head of the Department of Justice’s criminal division on 9/11, recalled, “We were shorthanded in terms of senior people….we essentially had to do double and triple-duty to pick up some of the responsibilities that would have been taken by others who were confirmed.”

Following a bitter five-week struggle, John Ashcroft was confirmed as attorney general on Feb. 1, 2001. His deputy, Larry Thompson, was confirmed on May 10, along with Assistant Attorney for Legislative Affairs Daniel Bryant.

Excluding U.S. marshals and attorneys, DOJ had 34 Senate-confirmedpositions in 2000. But Just 41% of those jobs were filled on 9/11. Half of those 14 officials—including then FBI Director Robert Mueller–were on the job less than two months before the attacks.

Bush’s State Department, supported by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, moved faster than other committees in the early days of the administration, but then slowed its pace. Before June, the State Department filled 20 of 44 Senate-confirmed positions, excluding ambassadorships. On 9/11, just 24, or 55%, of the 44 positions at the State Department were filled.

Conclusion

In light of these delays, the 9/11 commission recommended that, “A president-elect should submit the nominations of the entire new national security team, through the level of undersecretary of Cabinet departments, not later than January 20. The Senate, in return, should adopt special rules requiring hearings and votes to confirm or reject national security nominees within 30 days of their submission.”

Both the Senate and the Biden team should work to meet this standard. And while the Senate should carefully scrutinize every nominee, it also should recognize that unnecessary delays could undermine the ability of the new administration to respond to the threats we currently face and those that are unexpected.

By Emma Jones

On Monday, November 23, the formal transition period officially began. The administrator of the General Services Administration, Emily Murphy, ascertained the results of the 2020 presidential election. This decision recognizes President-elect Joe Biden as the “apparent winner” of the election under the 1963 Presidential Transition Act and is a critical milestone in the transition process.

The official transition period of 78 days has been shortened to 57 days. The last time the country faced a shortened transition was in 2000. GSA’s delayed ascertainment shortened George W. Bush’s official transition to just 36 days. We have learned that delays can be costly to a successful transition. In 2002, the 9/11 Commission Report concluded that a delayed transition hurt the Bush administration’s ability to confirm key national security appointments critical to the safety of the country. Max Stier, president and CEO of the Partnership for Public Service, reflected on the upcoming challenges for the transition in a statement on Monday.

“Now that GSA Administrator Emily Murphy has fulfilled her duty and ascertained the election results, the formal presidential transition can begin in full force,” said Stier. “Unfortunately, every day lost to the delayed ascertainment was a missed opportunity for the outgoing administration to help President-elect Joe Biden prepare to meet our country’s greatest challenges. The good news is that the president-elect and his team are the most prepared and best equipped of any incoming administration in recent memory.”

Stier continued, “Moving forward, we must pursue statutory remedies to ensure that a transition is never again upheld for arbitrary or political purposes. A clearer standard and a low bar for triggering access to transition resources are crucial to protecting the apolitical nature of presidential transitions.”

“President-elect Biden and his team have already started their transition work, demonstrating skill, experience and purpose. Now they can continue with the full support of the United States government,” said David Marchick, director of the Center for Presidential Transition at the Partnership for Public Service. “Fortunately, federal career civil servants have done an outstanding job preparing for this year’s transition by producing fact-based information on critical agency issues and by designating acting officials who will lead agency operations until new political appointees are confirmed. They now need space to do their jobs.”

The Center for Presidential Transition released a list detailing the resources available to the Biden transition team now that ascertainment is complete. Those resources include $6.3 million in congressionally appropriated funds, 175,000 square feet of federal office space including Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities and most importantly, access to more than 100 federal agencies and the ability to process and clear presidential appointments. These resources will be critical for distributing a COVID-19 vaccine, repairing a broken economy and protecting the country’s national security interests.

For the benefit of the American people, the remaining work of the most important presidential transition of the century can now begin.

By Alex Tippett

One of the most important components of the transition from one president to the next is the sharing of national security information. New administrations need to be aware of the threats facing the country and what option they have at their disposal.

Each of the last three administrations took substantive steps to ensure their successors were fully prepared. Much of this work was done by career officials in various Cabinet agencies and in the intelligence community, but in recent years outgoing White House officials and national security staff have participated.

In general, an outgoing White House prepares memos and hosts in-person briefings for their replacements. Both the George W. Bush – Barack Obama and the Obama-Donald Trump transitions included preparedness exercises to simulate real-world national security scenarios. With the passage of the Edward ‘Ted’ Kaufman and Michael Leavitt Presidential Transitions Improvements Act of 2015, such exercises are now required.

The following are examples of how the last three presidents prepared their successors.

2000-2001: Clinton-Bush Transition

According to George W. Bush’s National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley, President Bill Clinton’s administration relied primarily on written memos and several in-person briefings. The Clinton team held briefings conducted by National Security Council staff along with a limited number of principal-to-principal briefings with senior Bush officials on threats posed by al-Qaeda and the North Korean missile program.

2008-2009: Bush-Obama Transition

The outgoing Bush administration put a heavier emphasis on principal-to-principal briefings. These included meetings attended by both the incoming and outgoing secretaries of State, national security advisors and White House counsels.On the Monday following the 2008 election, Bush personally briefed President-elect Obama on ongoing covert operations.

The Bush team also relied heavily on mid-level staff. They prepared about 40 memos on specific national security concerns beginning eight months prior to the election. Meetings with members of the Obama security team began after Thanksgiving.

The Bush administration also left contingency plans for a variety of possible scenarios, and organized two tabletop exercises where outgoing members of their national security team paired up with their incoming counterparts. Roughly 50 senior officials attended. The first was held in December and focused primarily on the NSC and best practices for foreign policy decision-making. The second, conducted on Jan. 13, simulated the response to a terror attack.

On Inauguration Day, the two teams met in the Situation Room to discuss an immediate terror threat, Iran and the war in Afghanistan.

2016-2017: Obama-Trump Transition

The Obama White House followed a similar model as they prepared for Donald Trump’s transition team. National Security Advisor Susan Rice briefed Trump’s choice for the position, Michael Flynn, four separate times. The Trump team experienced personnel issues and challenges securing security clearances, delaying the first contact between Obama NSC staffers and their counterparts until Nov. 22.

These in-person briefings were supplemented by 275 briefing papers. Several, however, had to be rewritten to exclude classified information because of problems with security clearances on the Trump team.

On Jan. 13, the Obama national security team and Cabinet hosted a preparedness exercise for their counterparts in the incoming Trump administration. This exercise included a simulation exploring how the federal government might respond to a pandemic.

By Lisa Haralampus and Chris Naylor

Government employees create and maintain federal records as an integral part of their daily responsibilities. Agencies must ensure employees are aware of their responsibilities regarding the management of records, especially during presidential transitions.

To assist agencies, the National Archives and Records Administration has created an online publication, “Documenting your Public Service,” that provides all government employees, including senior officials and political appointees, with information regarding their responsibilities for managing federal records.

For senior officials, many of their records are permanently valuable and one day will be sent to the National Archives to help document the country’s history. As senior officials often enter and leave federal service during times of presidential transition, there are several things they should know to properly manage and preserve their records.

Some key points to remember are:

- Keep personal business out of agency-administered systems and accounts.

- Keep agency business out of personal systems and accounts.

- Be aware that federal employees have no expectation of privacy in agency systems or accounts.

While working in federal service, records management should be routinely incorporated into daily activities and work processes.

Federal employees must always remember the following guidelines:

- Talk to the experts in your agency—the senior agency official for records management responsible for strategic planning and oversight of their entire records management program and the agency records officer responsible for implementing the agency records information management program and operations.

- If you create or receive a federal record in a personal or nonofficial email account, you must either include your official account on the “cc” line of any emails you send or forward a complete copy to your official account within 20 days.

- Remember that social media accounts created or used for official agency business must stay under the control of the agency.

When leaving federal service, remember specific recordkeeping responsibilities.

- Complete exit briefings on records management with your records management staff, IT liaisons and general counsel.

- Ensure federal records and information are available to your successor.

- Do not delete or remove government information when leaving office.

Federal employees cannot take records with them when leaving federal service, but they may be able to take some copies of federal records as well as their personal materials. Setting up good practices from the start of your career will make it much easier to manage federal records at the end of your service.

To further explain the obligations, NARA has developed transition specific guidance materials for political appointees covering the key points outlined above, including a one page handout and an online briefing video.

Lisa Haralampus is the Director of the Records Management Policy and Outreach program in the Office of the Chief Records Officer for the U.S. Government at the National Archives and Records Administration where she issues government-wide policies for federal agencies related to records management standards, technology and processes.

Chris Naylor is the Deputy Chief Operating Officer at the National Archives and Records Administration and is currently serving as NARA’s Presidential Transition Director.

By Alex Tippett and Paul Hitlin

After winning reelection, fifth-year presidents should be well positioned to pursue their policy agenda. Modern two-term presidents, however, have tended to struggle in their fifth year. This is largely because recent administrations viewed the transition from a first to a second term as a continuation rather than a time of change and renewal.

A recent report produced by the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, with assistance from the Center for Presidential Transition, examines this phenomenon in detail. By examining the personnel, policy priorities and processes of past administrations, the article offers a roadmap for effective presidential fifth years. Presidents winning reelection have the opportunity to avoid pitfalls that have hurt previous administrations and begin their second terms in a stronger position.

https://millercenter.org/contested-presidential-elections/breaking-fifth-year-curse

By Dan Hyman, Troy Thomas and Catherine Manfre

With less than two weeks until Election Day, much of the nation’s attention is focused on the presidential campaigns. Behind-the-scenes, however, career civil servants are quietly preparing for a potential transition and a turnover of political appointees.

According to the federal transition law, agencies are required to complete three major tasks prior to Election Day:

- Submit updated lists of politically-appointed positions to the Office of Personnel Management for compilation in the 2020 Plum Book.

- Create a succession plan for senior leadership positions by September 15.

- Compile agency briefing materials by November 1 to assist new administration officials or second-term leadership.

To date, more than 140 agencies have teams of career employees leading this transition work. Since May, the Office of Management and Budget and the General Services Administration have convened leaders from these teams to coordinate transition activities and facilitate the sharing of best practices.

Agencies have met the first two milestones and are working to complete their briefing materials by the November 1 deadline. In their simplest form, the briefing materials are like an “Agency 101” of the key facts, figures and issues. They enable new leadership to get up to speed quickly so they can hit the ground running.

Four tips to maximize the effectiveness of agency briefing materials

While federal law requires agency transition teams to “create briefing materials related to the presidential transition that may be requested by eligible candidates,” it does not specify what contents should be included. Based on guidance issued by OMB and GSA, as well as best practices from past transitions, the following tips will help agencies maximize the effectiveness of their briefing materials.

Tip one: Provide a baseline understanding of the agency

Recipients of briefing materials – whether they are transition review teams for an incoming first-term administration or newly appointed leadership for a second-term administration – will have varying degrees of familiarity with the agency prior to arriving. Some may have prior experience with the agency (though it is likely dated), while others could be experts in the policy area. These materials must provide readers with the agency’s full background and current context, including at a minimum:

- Organizational charts that include key positions.

- Recent budget history and a current budget proposal.

- Top issues and challenges.

- Congressional oversight committees and issues.

- Impact of COVID-19 on the agency’s priorities and internal operations.

Tip two: Be succinct

Agencies should focus on the top issues and the most relevant data. Recipients of briefing materials are busy individuals who may not have time to read lengthy reports. Many agencies have begun streamlining information to make it more digestible. During the 2016-17 transition, the Department of Defense created a series of one- and two-page papers on the top five to 10 priority issues they believed were most important to newcomers.

Tip three: Include key insights

The best materials go beyond agency statistics and conventional issues to provide insights into the challenges and opportunities facing new leaders. During the 2016-17 transition, the FBI linked its bureau’s locations with a list of threats to national security. They also created a map pinned with color-coded offices according to the year they opened. The visual representation of the bureau’s newest locations generated conversations on where emerging threats were located.

Key insights should include:

- The parts of the agency’s budget that have been most impacted by the pandemic.

- Significant changes in workforce demographics, such as the retirement of baby boomers and the number of employees eligible for retirement.

- The agency’s current top priorities.

Tip four: Take advantage of digital formats

Historically, the briefing materials have been produced as reports in thick binders. However, digital versions make it easier to distribute to the intended recipients, especially now when so many federal officials and transition leaders are working remotely.

Creating succinct, comprehensive and informative briefing materials is a federal agency transition team’s most significant task. To learn more about briefing materials and other aspects of the federal agency transition process, check out our 2020 Agency Transition Guide. For additional information on the transition process as a whole, see our 2020 Presidential Transition Guide and visit the Boston Consulting Group’s transition homepage.

Dan Hyman is a manager at Center for Presidential Transition. Troy Thomas is a partner and associate director of the Boston Consulting Group and Catherine Manfre is a principal of Boston Consulting Group.

By Alex Tippett and Carter Hirschhorn

With less than three weeks to go before the presidential election, job seekers for either a Trump second term or a Biden first term are dusting off their resumes and positioning themselves for potential appointments.

During our Transition Lab podcasts, a number of transition veterans detailed some of the least productive approaches for prospective job candidates. The following is a list of five lessons derived from these conversations. If you stick to them, you can reduce the possibility that your resume ends up in the recycling bin!

Avoid overwhelming the transition team

Prospective appointees sometimes think the best way to get a job is to have all their friends call the transition team or the White House personnel office with words of support. Don’t do it!

During a transition and in the early days of an administration, there can be anywhere from 150,000 to 300,000 applications for presidentially appointed positions. Unnecessarily adding to that workload will not make you any friends.

Liza Wright, who directed the Office of Presidential Personnel (PPO) under President George W. Bush, said, “To have all of these people start berating the office with phone calls and things like that…is not a good approach.” Jonathan McBride, who ran PPO under President Barack Obama, added, “If somebody can speak to the substance of what you can do or your acumen…that’s great. Twenty people saying that they like you does not help. And it becomes a judgment question after a while. If you approach this [job search] this way, when you’re acting on behalf of the president of the United States, are you going to show similar poor judgment?”

Job applicants should wait until after the election to send in their resume. Right now, you should secure letters of recommendation and start filling out the necessary clearance and disclosure forms. Carefully calibrate the way you demonstrate your support.

Stay out of the press

There is always a temptation for job seekers to audition in the media. This is a mistake. Press stories can create headaches for the transition teams and distract from the only campaign that matters—the presidential campaign.

Speaking with reporters Nancy Cook and Andrew Restuccia about their transition coverage, Transition Lab host David Marchick pointed out that “the lesson here for someone who wants to get a nomination is not to be in one of these stories because you might have a better chance of getting the job if you’re not in the story.”

Don’t be presumptuous

For every job in an administration, there are dozens if not hundreds of qualified applicants. Even if you have served before, there is no guarantee you will get the job you want. Ironically, accepting that reality might increase your chances of getting a job.

According to Michael Froman, who led the Obama 2008-2009 transition personnel effort, “People who came in and said, ‘I am the greatest expert in this area…where do I fill out my employment forms,’ usually did not get hired.” Froman said. “The more successful approach was to make clear that that you were low maintenance,…that there were a variety of positions that you could envisage yourself doing, that you were not insistent on necessarily being the top person in any agency, but you were willing to play whatever role the president-elect felt was appropriate for you.”

Don’t show up unprepared

While you should not assume you will get a specific job, you should have a sense of what types of jobs you are interested in.

“I always tell people to do your homework,” Wright said. “It’s so helpful if someone has gone to this kind of taking the steps to really research what positions in the government they’re interested in, what they believe they’re qualified for.”

Doing this legwork will show you are committed and thoughtful, and that might just win you some friends. Coming unprepared, however, might cost your resume a second look.

Don’t wait until your nomination hearing to be honest – disclose all information from the start

Potential nominees should be straight-forward with the transition team. Clay Johnson, who led George W. Bush’s personnel operation during the transition and also served as PPO director, told candidates, “I’m expecting total honesty from you…and if it turns out you have problems or conflicts, and you aren’t able to serve, you have to know that we’re going to drop you like a hundred-pound weight.”

What should you do pre-election? Support your preferred candidate and get ready. Part of this process involves familiarizing yourself with financial and ethics forms and preparing those materials so you are ready if the next administration would like you to serve. If you have questions about these forms, consider registering for our October 21 Ready to Serve webinar about financial disclosures, or viewing our previous two sessions on YouTube.

By Alex Tippett and Troy Cribb

During election seasons, the status of political appointees in the federal workforce come under increased scrutiny. Under all recent presidents, some political appointees have attempted to become civil servants — a process commonly called “burrowing in.”

Unlike political appointments, civil service positions do not terminate at the end of an administration. Conversion therefore allows political appointees to stay in government after the president who appointed them has left office.

These kinds of conversions inevitably create concerns. Supporters of an incoming president may be suspicious of individuals hired by the previous administration. More broadly, some fear conversions can violate the merit system principles that govern hiring in the federal civil service.

The hiring process for civil servants is designed to promote a professional, apolitical workforce and to prevent discrimination, political favoritism, nepotism or other prohibited practices. To ensure these rules are followed, the Office of Personnel Management reviews requests to move a political appointee into the civil service. This review is designed to prevent improper conversions while providing talented individuals with the opportunity to join the civil service.

How does OPM conduct oversight?

While OPM has reviewed conversions since the Carter administration, the process has changed over time. Currently, agencies must submit a request to OPM whenever they seek to hire a current political appointee or one who has served in a political position within the last five years. OPM conducts multi-level reviews of each application to make sure the conversion follows federal hiring guidelines.

If OPM believes a conversion violates federal hiring laws or regulations, it may reject the conversion. If OPM finds the agency’s conversion attempt violates the federal government’s prohibited personnel practices, it may refer the issue to the Office of Special Counsel for investigation.

On occasion, agencies have converted political appointees without going through the OPM review process. In those cases, OPM retroactively reviews the conversions and issues any necessary corrective actions, which can include re-advertising the position. Recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the firing of an appointee who had converted to a career position without an OPM review.

OPM’s procedure is not laid out in statute. Instead, existing laws and regulations broadly empower OPM to protect the civil service’s merit system. Individual OPM directors have interpreted this authority differently, with the rules tightening over the years. Previously, agencies only had to file a request for a smaller subset of political appointees and only for conversions taking place close to an election. OPM’s current regulations require that every conversion receive approval.

Congress also created specific reporting requirements for conversions. The Edward “Ted” Kaufman and Michael Leavitt Presidential Transitions Improvements Act of 2015 requires that OPM submit an annual report to Congress detailing the conversions. During the final year of a presidential term, these reports must be submitted quarterly.

How common is burrowing?

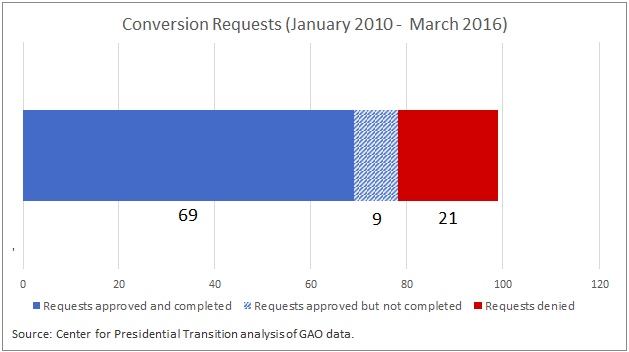

Investigations by the Government Accountability Office suggest that conversions are relatively rare. According to GAO’s most recent report in 2017, OPM received 99 conversion requests from January 2010 to March 2016. For context, during that period, the federal government hired about 100,000 people every year into full-time permanent positions.

Of those 99 requests, OPM approved 78, suggesting that most conversions followed proper procedure. The GAO found no reason to disagree with OPM’s assessments.

Of the 78 requests approved by OPM in the latest GAO report, only 69 were carried out. Occasionally, an applicant will decline to take the job after it is offered to them.

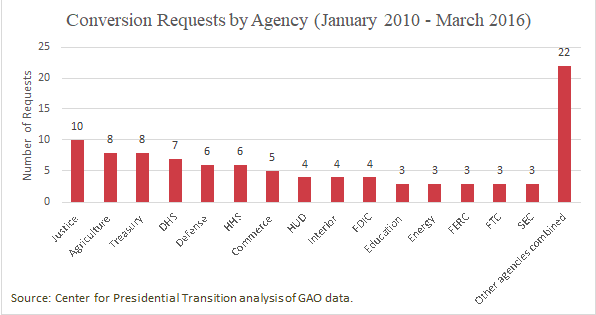

A relatively small number of agencies have accounted for a large portion of conversion requests. Between January 2010 and March 2016, approximately 10% of requests were initiated by the Justice Department. The top five agencies—Justice, Treasury, Defense, Agriculture and Homeland Security—accounted for nearly 40% of the conversion requests filed.

Some agencies have occasionally failed to request permission from OPM before carrying out conversions. There were seven instances of this cited by the GAO. When this occurs, OPM carries out a post-appointment review as soon as it becomes aware of the conversion.

Conversions themselves also tend to increase immediately before an election. While available data is incomplete, 47 conversions occurred in the final year of President George W. Bush’s presidency, up from 36 the previous year. At least 19 occurred in President Barrack Obama’s fourth year, up from 11 the previous year. GAO’s 2017 burrowing report does not include the final months of Obama’s administration or the entirety of the Trump administration.

Additional public data would be helpful

While the law requires OPM to report instances of burrowing to Congress, neither the agency nor the House Committee on Oversight and Reform or the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs have made the information public. Doing so is in the public interest and could help guard against potential abuses.

Chief financial officers play an essential role in the stewardship of the federal government’s resources, guiding agency finances, strengthening the capability of the workforce, meeting customer needs and using new technologies to improve payment accuracy. As we approach the 30-year anniversary of the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, there have been continual improvements of financial management systems and audits, and greater use of technology and data to increase the government’s ability to make informed decisions.

While CFOs have played an essential part in these developments, challenges remain. The role of the CFO has not been updated since the 1990 legislation. Many agencies are still working to implement core elements of the statute, and several agencies remain out of compliance with the law’s technical requirements.

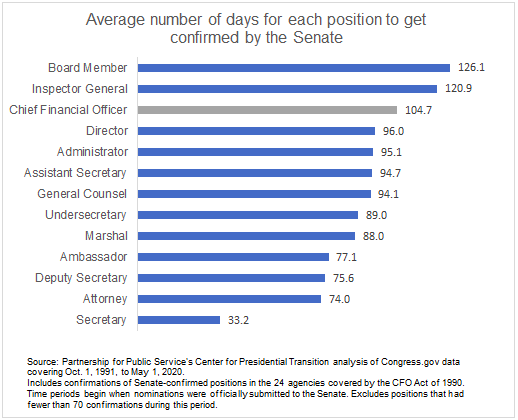

Another challenge has been the low priority given to CFOs by the Senate. One indication is the amount of time the Senate takes to confirm CFO appointees. For the nearly three-decades since the CFO law was enacted, the Senate has taken an average of 104.7 days to confirm CFOs. That is the third-longest average for any type of job within these agencies behind only inspectors general and members of various government boards.

A recent report produced by the Partnership for Public Service and Deloitte, “Finance of the Future,” made recommendations to modernize the role of CFO. One recommendation called for standardizing the position government-wide by delineating a common set of core responsibilities. This would enhance their ability to integrate and share information across agencies, transfer institutional knowledge and standardize functions.

Another recommendation called for improved continuity in CFO leadership. Currently, 15 of 24 federal CFOs are Senate-confirmed positions while the others are career positions. Congress should consider converting all CFO jobs to career positions or establishing the role as a fixed term with a performance contract. In that situation, CFOs would be expected to remain in office even with a change in administration.

Many of these recommendations are contained in a bipartisan bill proposed by Sens. Mike Enzi, R-Wyo. and Mark Warner, D-Va.

To meet the evolving needs of federal financial management, the Senate and agencies should make changes to better position CFOs to fulfill their obligations to the American people.

By Katie Malague and Dan Chenok

Building on the exponential growth of artificial intelligence over the past decade, federal agencies are using intelligent automation to further improve productivity. Intelligent automation incorporates AI, blockchain, cloud computing, robotics and other technologies, and is collectively transforming how agencies work—from managing paperwork to using data for decision-making to providing services to customers.

Indeed, past presidential administrations recognized the potential of artificial intelligence and other technologies and paved the way toward more complex use of intelligent automation: first through the National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan to maximize the benefits of federal AI funding, then through the American Artificial Intelligence Initiative to accelerate AI adoption.

Whatever the outcome of the presidential election, leaders can build on these initiatives to make government operations more effective and efficient and service delivery seamless.

The Partnership for Public Service and the IBM Center for The Business of Government hosted five events this year with agencies that moved from technology pilot projects to full-scale adoption: the U.S. Marine Corps, the General Services Administration, the Department of Defense’s Joint Artificial Intelligence Center, and the departments of Homeland Security and Health and Human Services.

These events highlighted lessons for the administration to consider for its AI plans and policies, and for effective adoption of intelligent automation:

- Start with the problem, not the technology. AI and other technologies should not be spread around like peanut butter. Agencies should focus on users’ needs and process improvements to determine if technology tools would be useful to boost performance. The Marine Corps’ approach, for example, is to adopt AI tools that will help Marines solve problems and become more effective.

- Foster a culture of innovation. Supporting innovation would help reduce agencies’ risk aversion and fear of failure and encourage employees to pursue new approaches for working more efficiently. The Marine Corps fosters a culture of innovative thinking, both in business operations and war zones—leading the Marines to adopt new technologies, including AI, to become more effective. Other agencies could seek advice from the GSA, which supports innovation government-wide by, for example, helping agencies adopt new technologies and organizing the Presidential Innovation Fellows program.

- Free employee time to focus on higher-level tasks. Tools that perform repetitive tasks free employees to tackle complex tasks only people can do. DHS, for example, is using AI in its Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System to help acquisition professionals find data about contractors and make better procurement decisions.

- Minimize bias by encouraging diversity of thought. When making decisions about AI and the data it relies on, pulling in diverse stakeholders helps minimize bias and inaccuracies. The DOD Joint Artificial Intelligence Center and its data governance council engages a diverse group of stakeholders when making data-related decisions. Stakeholders could include engineers, security experts, data scientists, ethicists and other specialists from government, industry and academia.

The event recordings are available on the Partnership’s website, and event summaries are on the IBM Center’s blog.

Katie Malague is the vice president for government effectiveness at the Partnership for Public Service.

Dan Chenok is executive director of the IBM Center for The Business of Government.

The Partnership and the IBM Center have collaborated on several other resources a second or first-term administration in 2021 might use to help government take full advantage of artificial intelligence. In our 2018 report, “The Future Has Begun,” we presented examples of the government’s successful use of AI. In the 2019 reports, “More Than Meets AI” and “More Than Meets AI Part II,” we explored impacts on the federal workforce, as well as issues of ethics, bias, security and privacy.